It helps to think about the city using analogy and metaphor for how it developed through time and space: the vortex and the palimpsest.

Use the idea of the vortex to think about the city’s uptown growth through time.

The Vortex

If Manhattan were stripped of its towering skyscrapers and scaled back to a human perspective, the city’s development and neighborhoods we see today were largely shaped within just a few transformative decades.

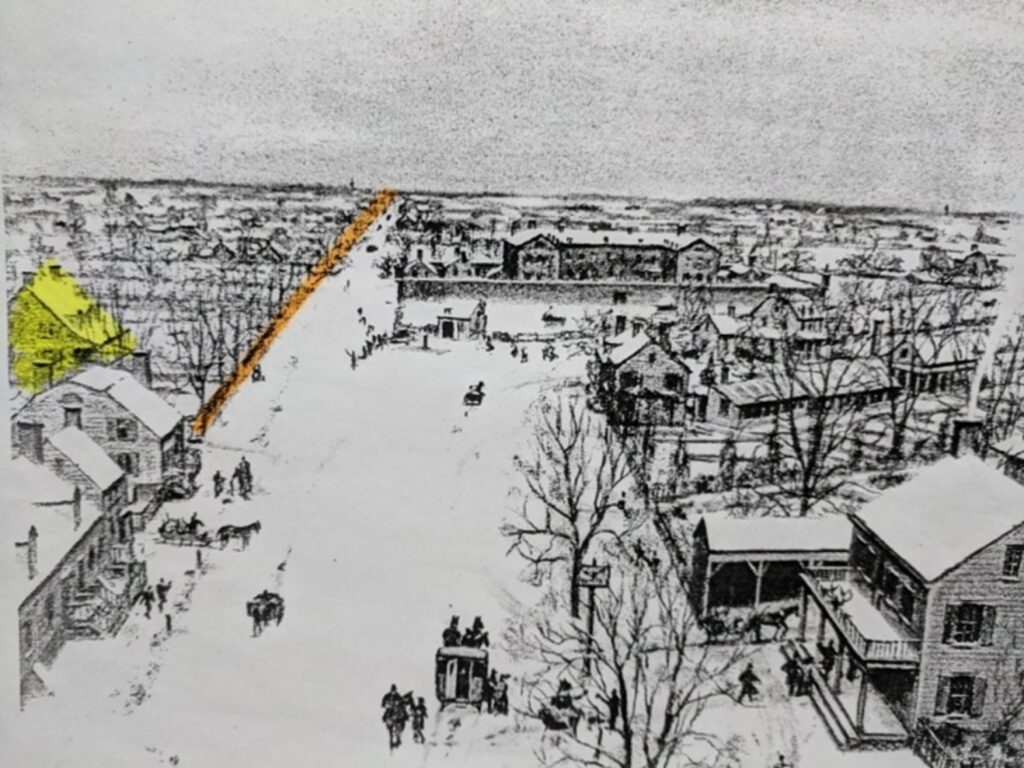

Consider this 1828 image of Madison Square described in As You Pass By, by Kenneth Dunshee (1952), three years after the Erie Canal opened. The view is from the site of the Flatiron Building at 23rd Street and Broadway, looking northward.

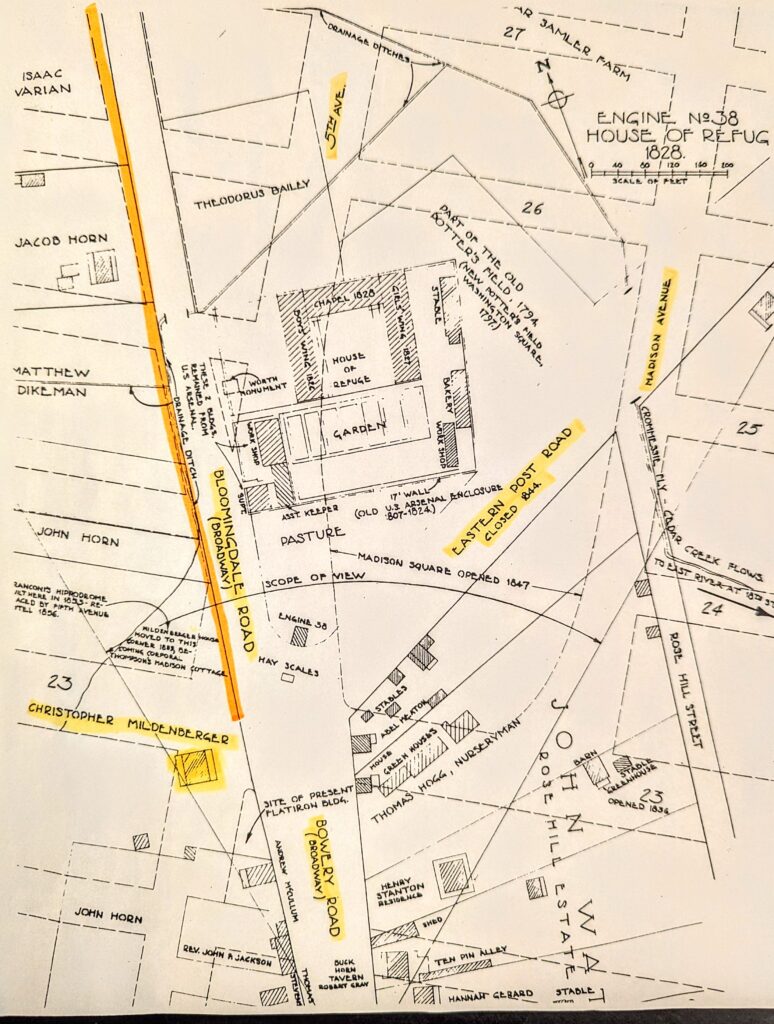

The orange path in the image is Broadway, the sole artifact left from that time. The highlighted structure marks the location of the Christopher Mildenberger farmhouse, once standing at the crossroads of Fifth Avenue and 23rd Street. Nearby lay the imposing walls of the House of Refuge, a juvenile reform school and penitentiary. Meanwhile, the city’s most opulent hotels, shopping destinations, and theaters were located two miles downtown, clustered around City Hall.

A little about the underlying geography before getting to how quickly the city moved through.

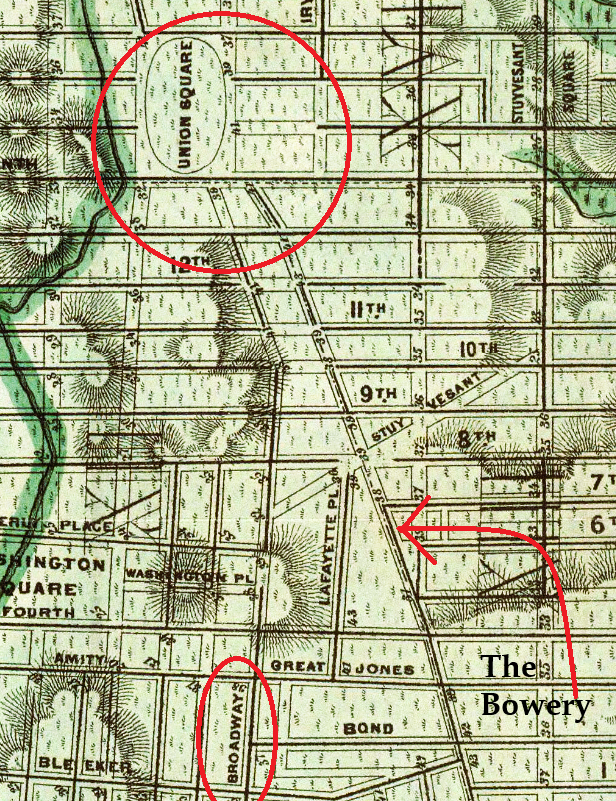

Ten blocks below Madison Square, Broadway and the Bowery terminate at 14th Street, about 200 feet apart just below Union Square (and why the name). Continuing uptown from Union Square, the Bloomingdale Road, in the basic path of future Broadway, went up the west side and the Boston (or Eastern) Post Road (crossing in front of the House of Refuge), went along the east side. Coming up from Wall Street, the fork in the road shows the original paths of routes 9 and 1, respectively.

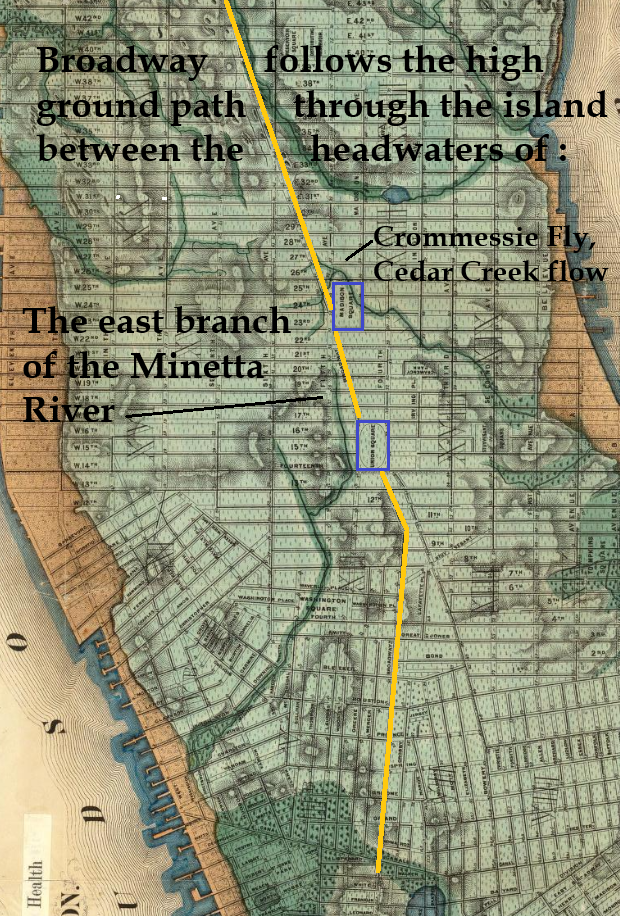

The road junction between Union Square and Madison Square sat on high, dry ground between the sources of two rivers—the Minetta and another river that lent its name to Gramercy Park—flowing in opposite directions toward the Hudson and East Rivers. The segment of the Viele Map on the right shows Broadway’s path across this localized version of the Continental Divide.

Less than eighty years after Madison Square resembled a pastoral landscape, Times Square was hosting New Year’s Eve celebrations at 42nd Street, while the New York Public Library was being built farther uptown on Fifth Avenue, which hadn’t yet reached Madison Square. People born when a stone bridge was required to cross Canal Street in the 1810s, could have lived to see the first Times Square ball drop for New Year’s Eve in the 1900s.

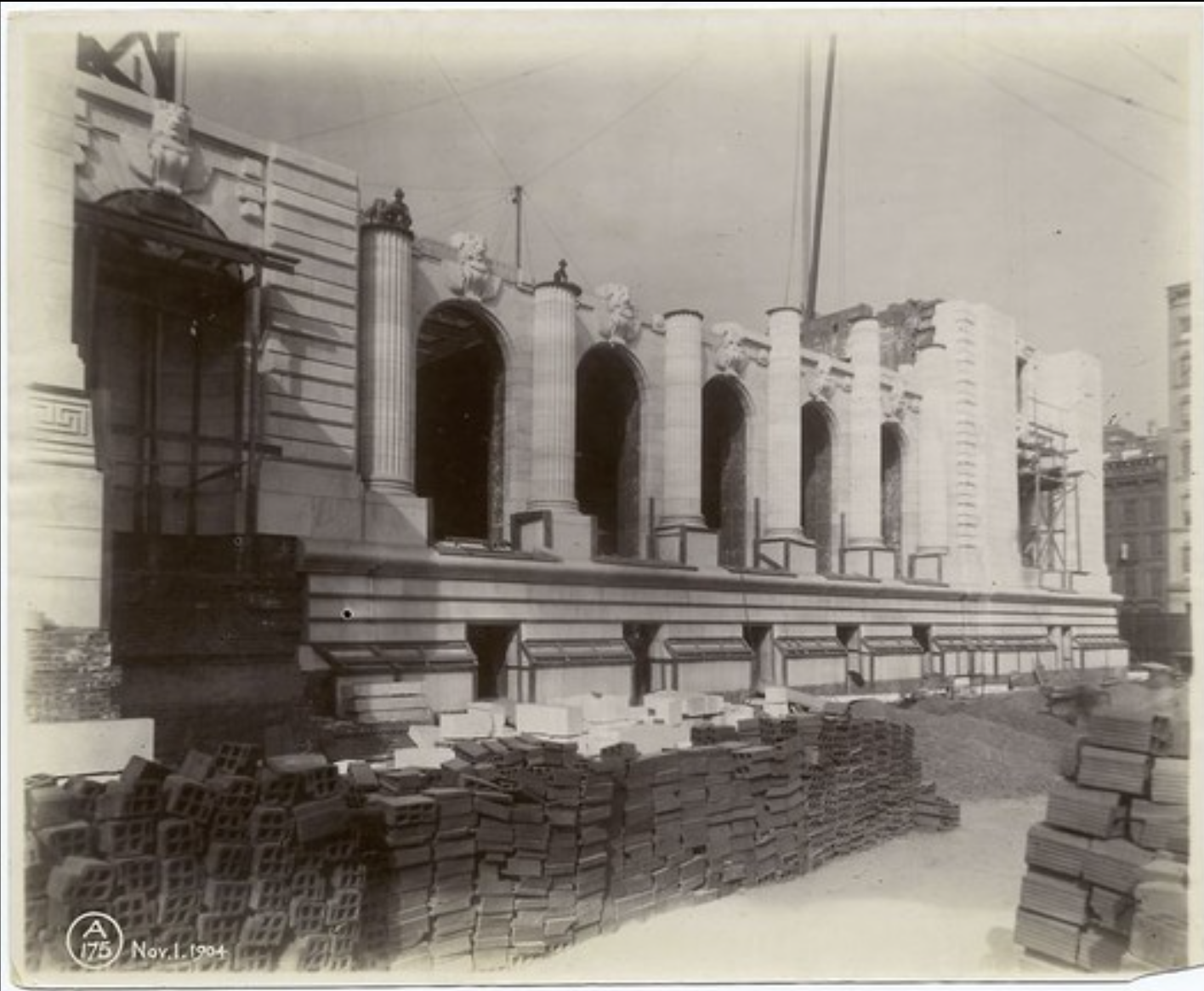

Times Square, 1904

The New York Public Library under construction, view from southeast corner, 1904

In a matter of decades after the opening of the Erie Canal, Manhattan was covered with miles of continuous, and often contiguous buildings. Architecture became a force of nature as construction, and the “city,” swept uptown at the pace of the business cycle; if it wasn’t homes uptown, it was commercial buildings downtown.

All three waves co-mingled for a brief time in Madison Square. When Met Life moved into the area in 1893, families like the Astors and Schermerhorns continued to live nearby for a few more years.

Steel frame manufacturing loft buildings followed Met Life up Fifth in the 1910s, just as 20 year old department Stores on Sixth Avenue were being converted to hospitals and factories.

The Garment District of the 1930s-1960s, and the Midtown Business District of the 1950s-1990s, completed the commercial business district development that had been pushing the city uptown with cast iron buildings since the 1850s.

The Palimpsest

Much of Manhattan is relatively easy to understand. The Garment District has factories and offices; Times Square has theaters and skyscrapers; Midtown has office buildings; the Upper West and East Sides are basically suburbs. We can explain the Lower East Side, Tribeca and the Financial District. But how do you explain Madison Square and SoHo?

Massive immigrant waves and explosive economic production twice saw a city of hotels, shops, and theaters relocate in the 19th century, through New York neighborhoods the size of small towns. Each time moving in were larger buildings for manufacturing, wholesale and production, along with some early office buildings. In part because the commercial business buildings of SoHo and Madison Square are from the 19th century, and every wholesale, loft, and even factory building was a calling card for the business itself; a business competing with many other businesses in ever more beautiful buildings. Before conventions and telephones, visiting merchants, agents and buyers connected with sellers from Broadway storefronts with signage and whatever architectural style stood out amongst the evermore outrageously ornamented facades. They are the most beautiful buildings ever built for what we’d consider today very mundane, commercial purposes; some of the blockfronts can look like a coral reef.

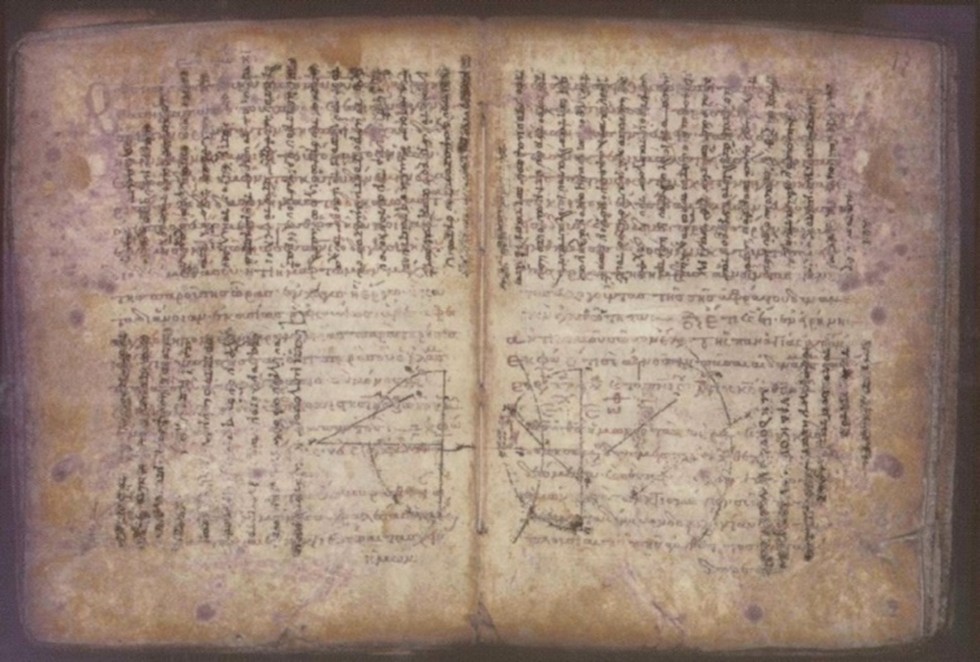

To understand the timeline of history, though, and what moved uptown, the palimpsest is the best visual tool.

The Palimpsest

Before paper, palimpsests were materials used by scribes (parchment, papyri, and vellum) that were refurbished and reused, sometimes repeatedly. They often show the remnant accumulations of past writings on the surface.

The palimpsest is an intuitive way to think about cities as places where layers of history are built over one another, and vestiges of the past continue in the streets in the ongoing life of the city. The palimpsest idea carries with it the authenticity (with some due diligence) of letting the built environment tell a singular story of origin and process, leveraging the city itself as the primary source for decoding a highly integrated, deeply interwoven built environment.

It is not a perfect metaphor, which can be good in this case. Unlike an actual palimpsest, Manhattan’s uptown-moving waves of history were “written’ as part of a continuous whole. As cast iron buildings went up in SoHo, brownstones went up in Madison Square; as steel frame buildings went up on Broadway in SoHo, and shops and theaters went up in Madison Square, mansions went up on Fifth Avenue across from Central Park.

Imagine a palimpsest where layers inform one another, make more sense, or take on an entirely different meaning, when read together? For a city like New York, whose most complex history has been “set in stone” for some time, attempting to reverse engineer how or why Manhattan’s thousands of buildings ended up where they did, in the combinations they did, in the neighborhoods they are, it seems, is only even possible through the lens of the palimpsest. It is a powerful tool not just because a typical Manhattan block has buildings from four, five or more periods of development, many American cities do, but New York’s intense sections of redevelopment measure in miles, not blocks.

Select Bibliography

Burrows, Edwin G. & Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, Oxford University Press, 1999.

Dunshee, Kenneth, As You Pass By, Hastings House, 1952.

Lockwood, Charles, Manhattan Moves Uptown, Houghton Mifflin, 1976.

Stern, Mellins, and Fishman, New York 1880: Architecture and Urbanism in the Gilded Age, Montacelli Press, 1999.

Stern, Gilmartin, Mellins, New York 1930: Architecture and Urbanisn between the World Wars, Rozzoli, 1987.

White, Norval, New York: A Physical History, Athenuem, 1987.

Internet Resources

Daytonian in Manhattan, Tom Miller

The New York Historical (formerly The New York Historical Society)