Following on the post: The Vortex and the Palimpsest: Seeing the City through Time and Space, here we look at the facades and sides of individual buildings and what, if anything, they reveal about history.

The palimpsest is not a new way of looking at cities. Around the built environment, it most often describes the markings left on the side of a building from a past neighbor, usually cornices, gables, and/or chimneys, sometimes called “ghosts.” They are informative artifacts of the past; a kind of brick-and-mortar DNA of the built environment.

Here are examples of ghosts around the city:

A gable roofline on White Street (above) west of Broadway is from an early 19th or even late 18th century structure. The featured image is a similar ghost on a pre-law tenement on Market Street..

A Midtown building (above) shows the roof line of a former neighbor, likely a brownstone. The exposed wall is reinforced with tie rods securing the floor joists to the wall where the home once braced the building.

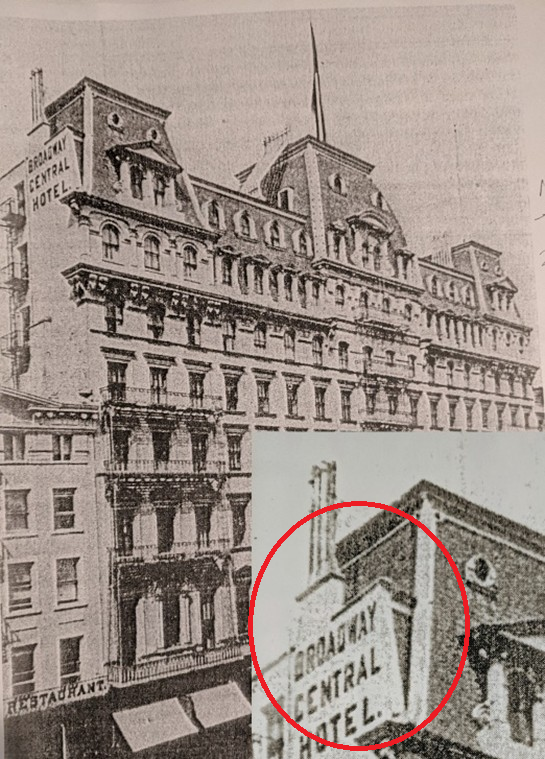

My very post in 2010 was this “ghost” of the Broadway Central Hotel (1870) on Broadway in NoHo (below), which left the incised mark.

The hotel collapsed in 1974; an NYU Law School dorm, Hayden Hall, stands on the site today.

But the palimpsest idea is an effective tool for decoding much more of the city; a building’s facade, a blockfront, and larger “super-block super-structures” can be read as palimpsests. The rest of this post will look at the building-as-palimpsest.

Building-as-Palimpsest

The facade can also be “read” like a palimpsest: Were floors added? A doorway moved? Does it retain its fenestration? Was it stripped of original details? Did styles accrete?

This is a small sampling of common alterations done to early Georgian and Federal buildings, most often homes, usually 2-3 stories tall with dormer windows, 20′-25′ wide, most earlier than 1840.

149 Mercer St., SoHo

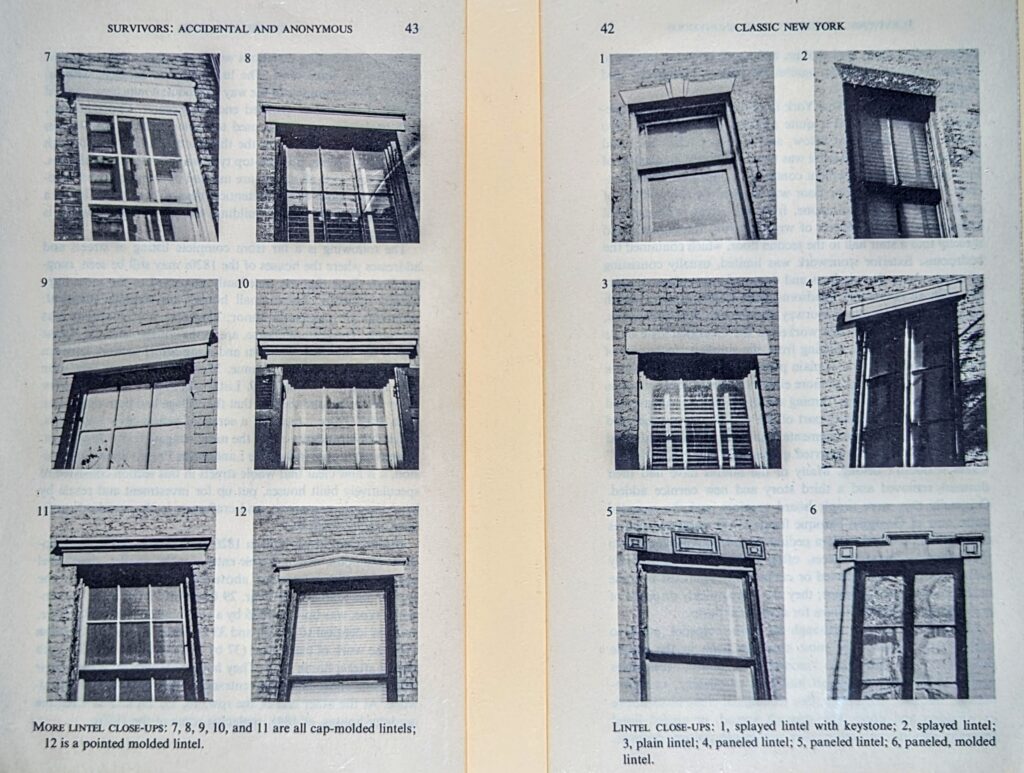

One can appreciate such details as lintels. In Classic New York, Ada Louise Huxtable said lintels, though not foolproof, could be helpful in dating a buildings.

The most common form in the simple builder’s house–and those “second class, genteel” residences of the 1820s were almost all builders’, carpenters’, or stone-masons’ houses–had a plain, flat, rectangular stone block above its windows and door. The splayed, spread, or angled lintel generally denotes an earlier, even eighteenth-century product.

There are interesting variations within the range of the twenties, some before, some after. The lintel may be paneled, with an incised groove running all the way around it; it may have paneled blocks at the end or paneled ends and center. Cap moldings, with projecting tops, were used to some extent in the twenties, but were most common in the thirties, and continued through the sixties. A plain, pointed-top type was popular in the thirties. But in every case all details are marked by simplicity and modesty; there is none of the pretentiousness of later styles. It was a timelessly tasteful way of building, and its dwindling legacy is to be cherished.

Lintels aren’t circled, features that are circled are described below.

57 East Broadway, Chinatown

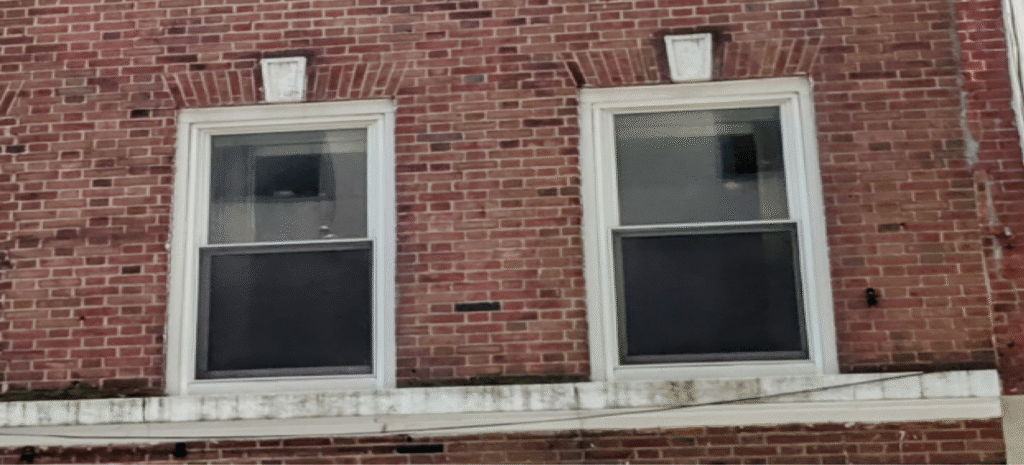

Dormer windows were likely removed and a floor added (above), as told by the different shade of brick on this East Broadway building in Chinatown.

Lintels: plain, pointed-top type, 1830s

1 w. 22nd St., Madison Square

The dimensions of this building, and where it is just off Fifth Avenue, help identify it as a former brownstone home, a probably one in a series of rowhouses.

51 Market St., Chinatown, across from the Manhattan Bridge

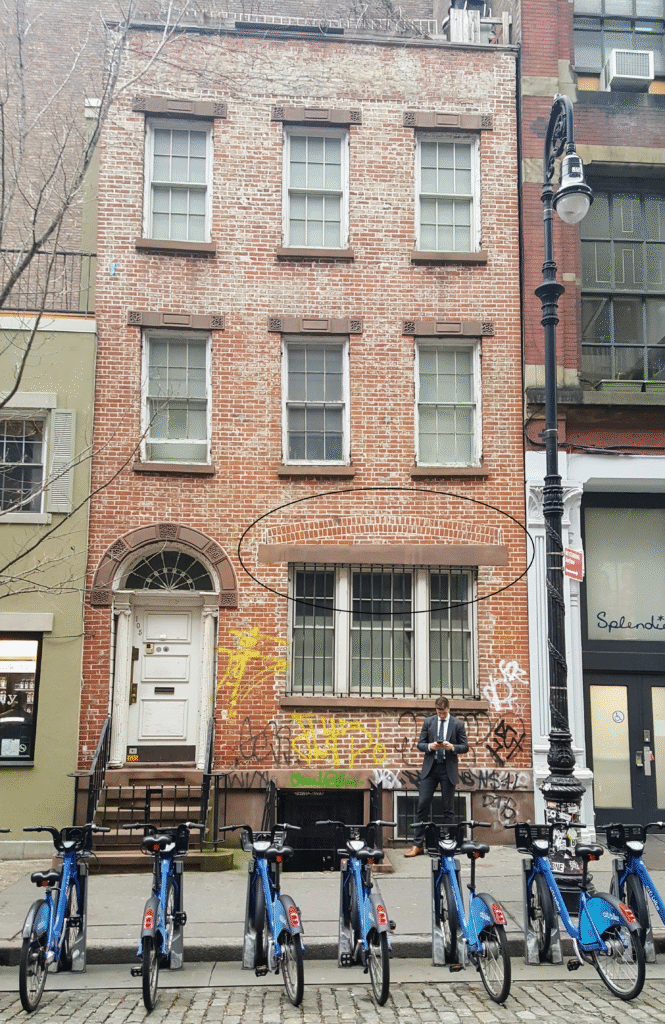

The 1820s Georgian home on Market Street (above) has an eclectic doorway combining Georgian, Federal, and Greek Revival elements from the 1830s, with an bracketed cornice added after 1850s when the Italiante style came in. Adding floors was a common renovation to New York buildings.

Lintels: paneled ends and center, ~1820s

345 Bleecker St., Greenwich Village

The asymmetrical facade, and slightly different shade of brick of this Bleecker Street home in Greenwich Village (above) shows where an alley or horse walk once led to a back house or stable.

Lintels: cap-molded. 1820s-60s

147 Bleecker St., Greenwich Village

Most Manhattan homes were built as row houses by speculative developers, and was lthe case here on Bleecker Street (above). The brickwork shows how the middle home was extended up. Lintels: pointed molded, 1820s-1860s

26 Cliff Street, Financial District

This Federal-style home (left) on Cliff Street in the Financial District had a floor added and windows blinded.

Lintels: splayed brick with keystone, early 18th c.

Greenwich Village

Another common alteration was to remove a stoop and give a new entrance to a building.

Llintels: plain, 1820s

108 Mercer St., SoHo

This home from around the 1810s looks like it was converted to commercial use, maybe in around the 1850s.

Lintels: paneled end and center, ~1820s

1-8 west 4th St., Greenwich Village

These four buildings on Washington Place were likely a series of 3 more row houses from the early 19th century. The arched lintels of the building on the right show that it was once a two-story structure, but the single floor of lintels surviving on the left (grooved block panels) suggest the buildings were as early as the 1810s.

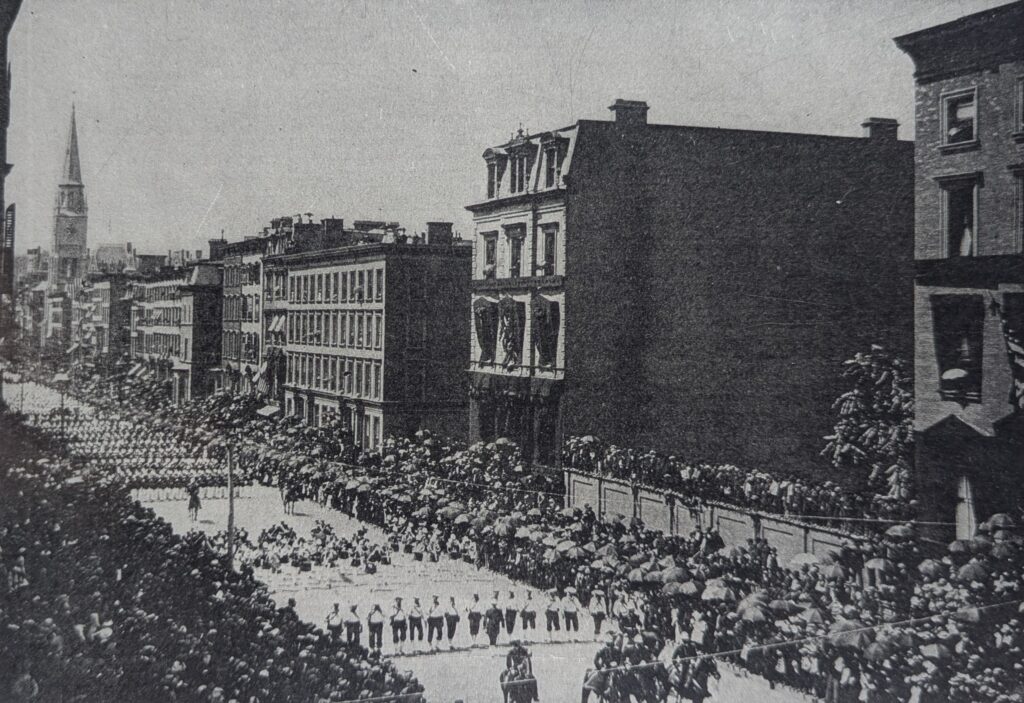

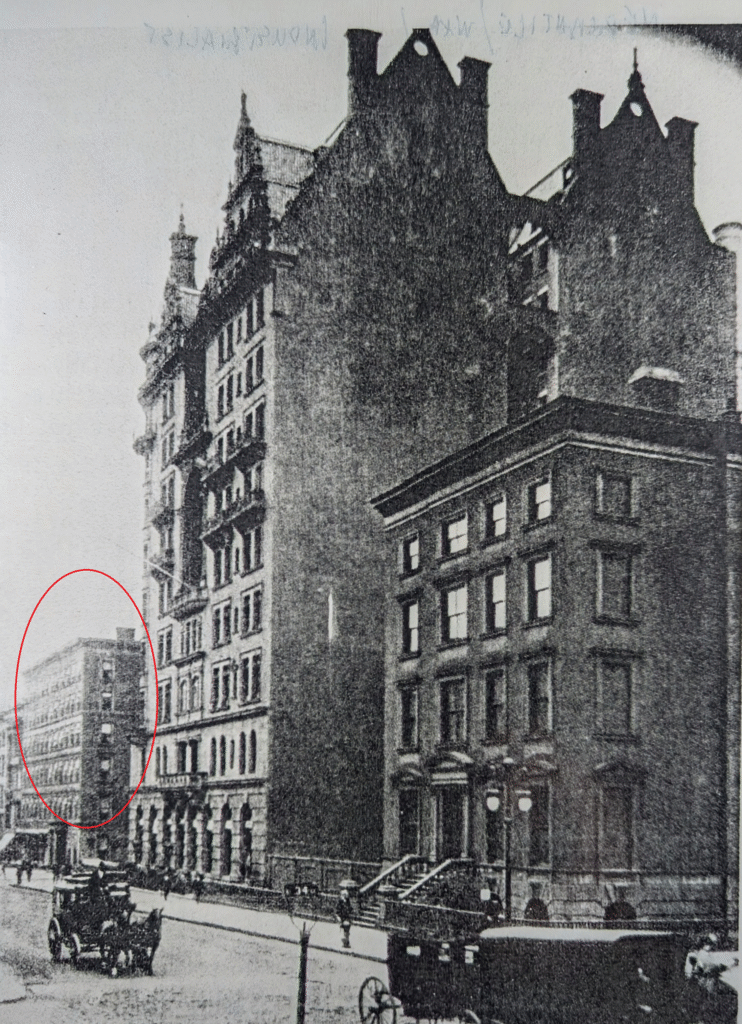

The image above captures Astor homes during a parade in 1886. The image at the right shows the Waldorf (1893) awaiting its counterpart, the Astoria (due in 1897), between 33rd and 34th Streets on Fifth Avenue—where the Empire State Building stands today. Notice the the buildings on the block to the south had two floors added in the intervening years.

Additional floors were added to commercial buildings as well.

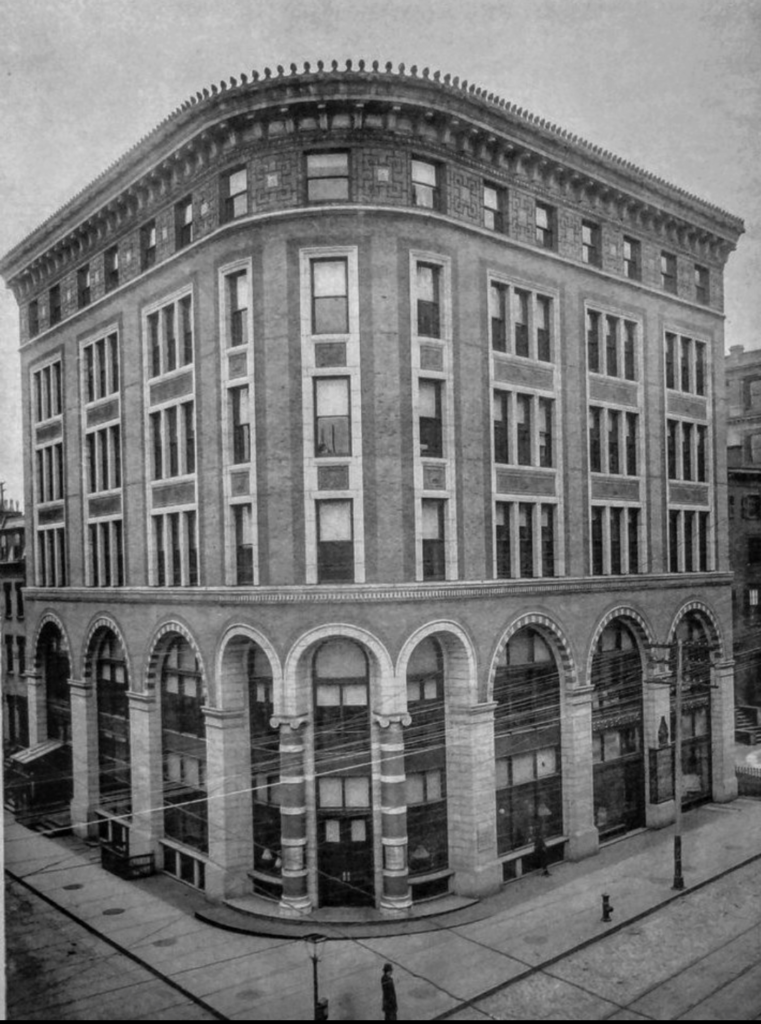

The Goelet Building, 900 Broadway & 20th Street, southeast corner, Madison Square

The Goelet Building (1886, McKim, Mead & White) was built as a commercial loft building in a fashionable part of town. It was extended five additional floors in 1905.

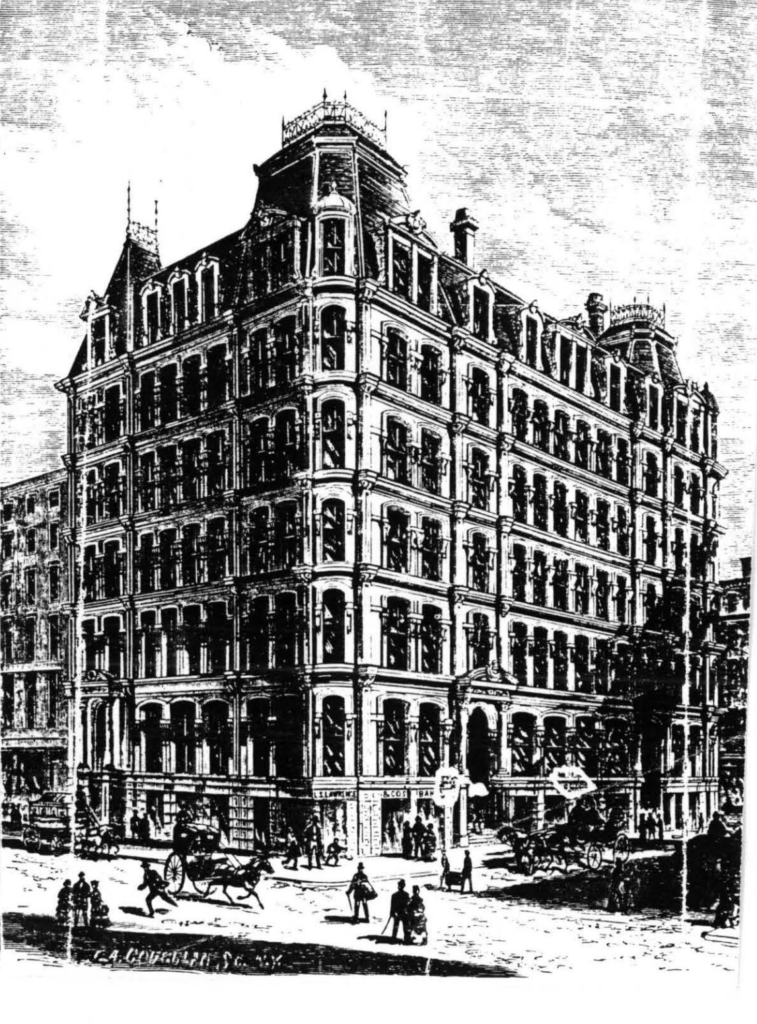

The Bennett Building, 93-99 Nassau Street, City Hall

The Bennett Building (Gilman, 1873; Farnsworth, 1890) for James Gordon Bennett Jr, owner of The New York Herald, was originally built as 6-story cast iron office building with a mansard roof in the early 1870s, and extended another four stories in the early 1890s for another owner.

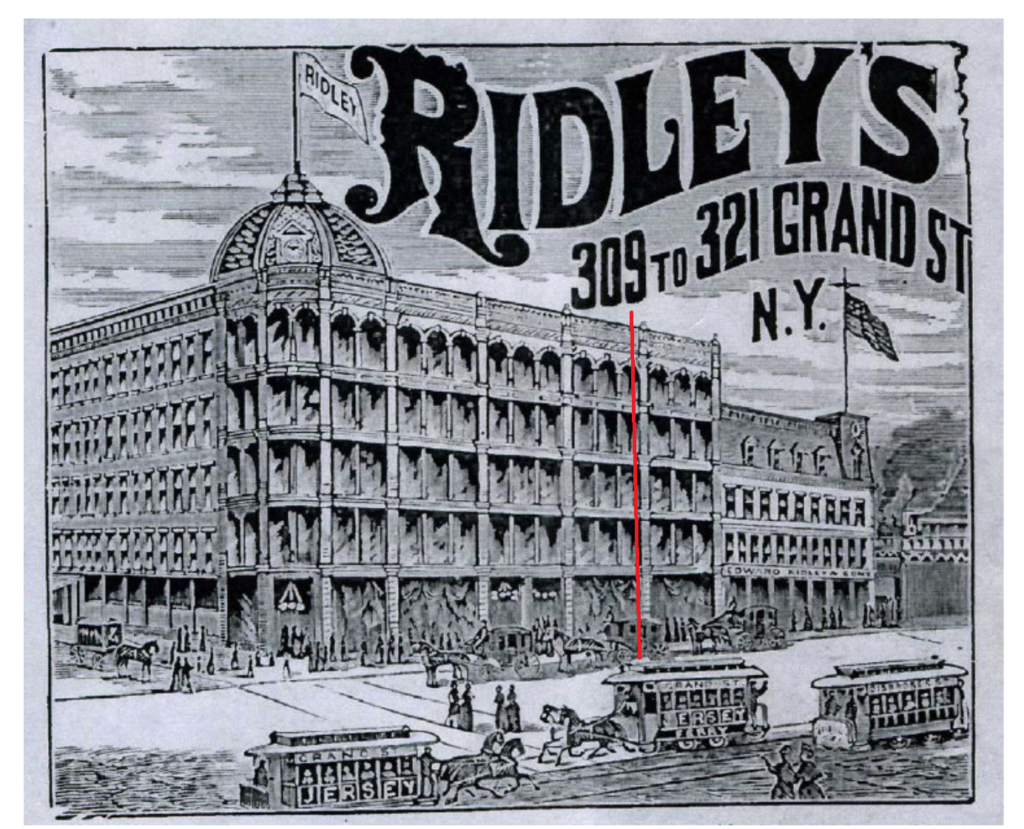

Sometimes buildings lost square footage. Below is what’s left of Ridley’s cast iron department store (1886), it was truncated when Allen Street was widened in 1932.

317-321 Grand Street, Lower East Side

The Renaissance Revival and Art Deco sides of the buildings invites some questions.

Select bibliography

Huxtable, Ada Louise, Classic New York, Anchor books, 1964.

Lockwood, Charles, Manhattan Moves Uptown, Houghton Mifflin, 1976.

Stern, Mellins, and Fishman, New York 1880: Architecture and Urbanism in the Gilded Age, Montacelli Press, 1999.

Stern, Gilmartin, Mellins, New York 1930: Architecture and Urbanisn between the World Wars, Rozzoli, 1987.

White, Norval, New York: A Physical History, Athenuem, 1987.

Internet Resources

Daytonian in Manhattan, Tom Miller

The New York Historical (formerly The New York Historical Society)