How do you “read” a blockfront like a palimpsest? In language, syntax refers to how word order gives rise to meaning. In a similar way, New York has its own “street wall syntax.” Here, patterns and distributions of buildings, or aspects of buildings, tell a story about the city’s growth and development.

Buildings have different aspects to them that shed light on how the city developed: their architectural styles and technological innovations, as well as their original purposes or functions. Each of these perspectives on the built environment provides a distinct narrative thread, and when combined, they allow us to unravel the layered stories of the city’s development.

Styles inform buildings and neighborhoods

As discussed in previous posts, architectural styles, while historically rich and interesting, are unreliable for making sense of a greater history for the simple fact that architectural anachronisms exist in the streetscape. As well, it was far easier to predict that a developer would have built a bigger building on a site, than the style they might have dressed it in.

That said, the blockfront is the city’s wallpaper, the street wall holds the physical energy of the city. It’s a little interesting to consider architectural, and trends in clothing and dress can sometimes align chronologically: hoop skirts go with brownstones and cast-iron buildings; the flapper dress goes with Art Deco; and the pill-box hat with the Modern skyscraper.

The difference is fashion goes in the closet, storage unit or museum, while the Manhattan block can look like a cocktail party with dress from different periods.

While architectural styles will be a part of future posts, they played little role in what was built where, when, and why, that is, they tell little of the story of New York City, a very human story.

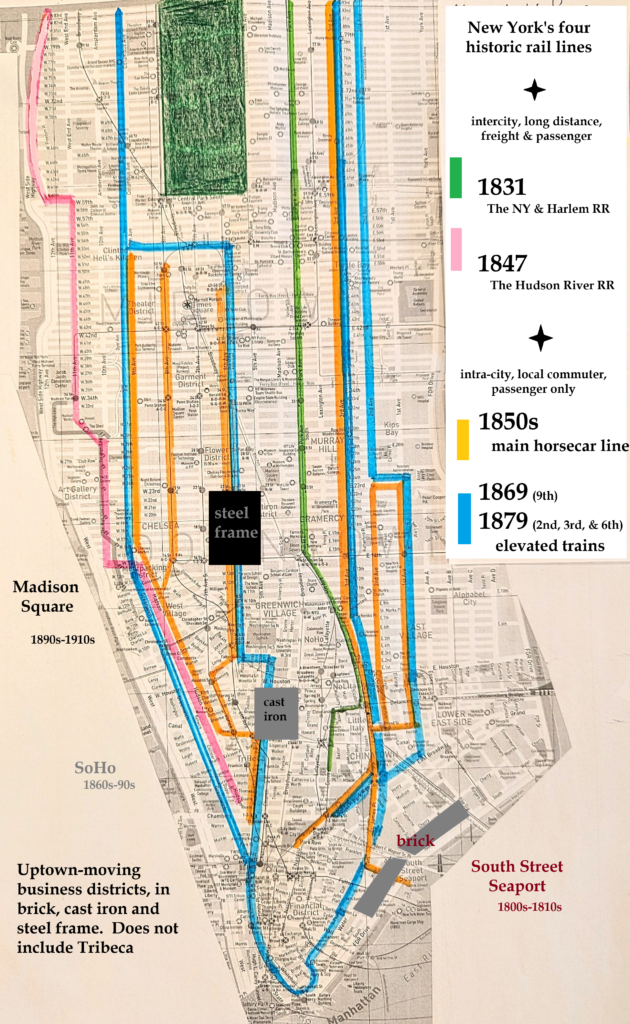

Technologies inform business districts

Patterns across Manhattan’s built environment are most clearly evident by building size as the city moved uptown. And just as cornice heights slope up between City Hall and Central Park, in the microcosm, the age order of buildings on a block can often accurately be predicted by ordering them smallest to tallest.

The three neighboring buildings on Broadway in NoHo (above) were built deccades apart, from tallest to shortest:

736 Broadway (1896, Louis Korn), store-and-loft, steel frame, Renaissance Revivial.

734 Broadway (1872, D & J Jardine), store, cast iron front, Neogrec.

732 Broadway (~late 1820s/30s), home, brick, Georgian/Federal

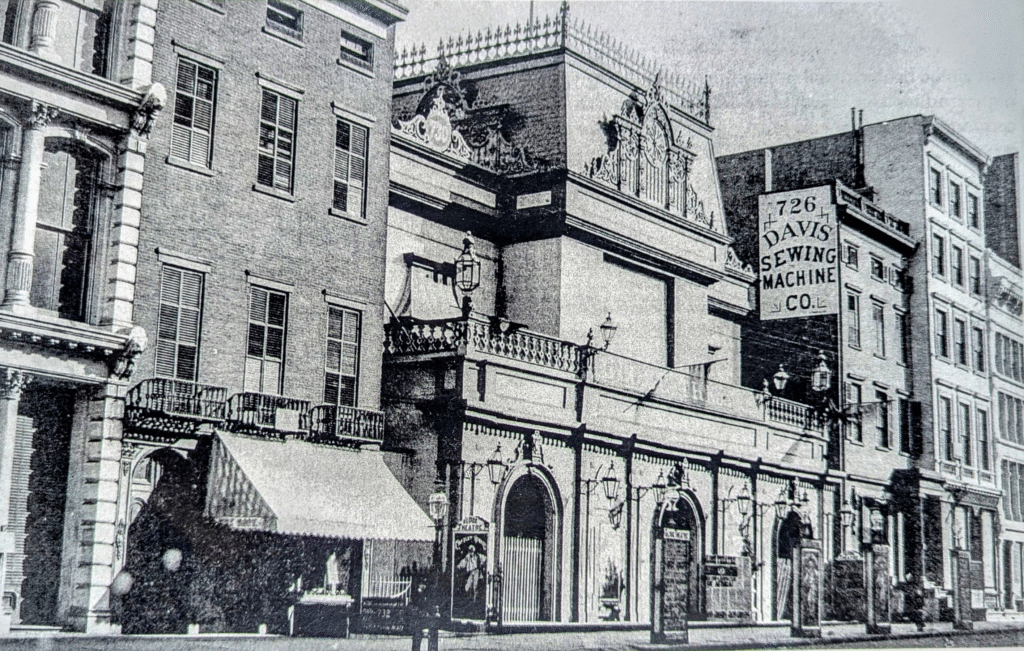

The 1865 image below shows a portion of the cast iron building at the left, and what had been upper class homes and a chirch in the 1830s, operating as commercial establishments and a theater in the 1860s.

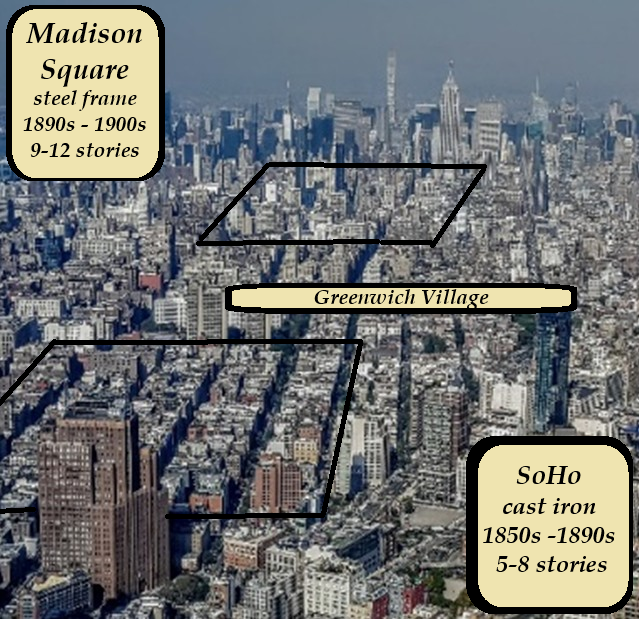

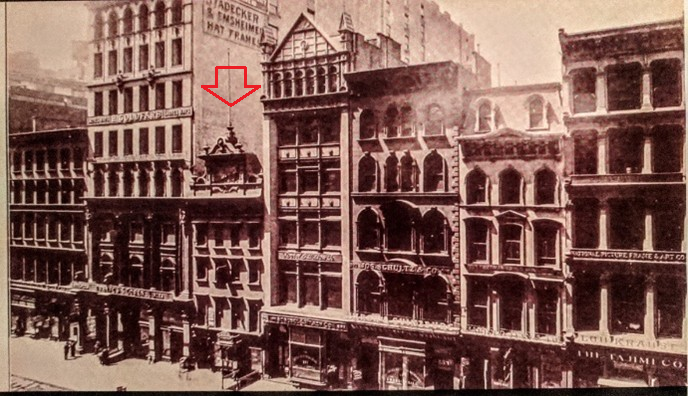

The three neighbors are a not so unusual combination of buildings that, in the macrocosm, reflect the uptown sequence of business districts in brick (the South Street Seaport), cast iron (SoHo), and steel frame loft buildings (Madison Square) that ran up through the middle of Manhattan.

From a previous post, these two images show how horse cars (1850s) and elevated trains (1870s), preceded the cast iron business districts of SoHo (1850s – 1890s) and the steel frame loft buildings of Madison Square (1890s – 1900s).

Business districts are the limit to what building technologies can say about the city.

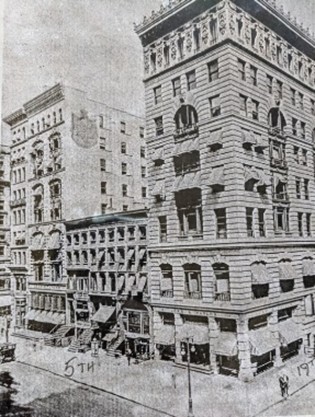

It’s true that brick and brownstone buildings were often homes, cast-iron buildings were often retail stores, and steel frame buildings were often factories. These permutations are well represented in history when New Yorkers lived uptown in brownstone homes, and shopped downtown in cast-iron stores, and steel frame loft buildings were almost invariably for manufacturing or wholesale.

But brownstone was used in commercial buildings and churches before the façade material swept the housing market.

And cast iron was used for commercial loft buildings in SoHo and Tribeca more than anywhere else; and the Bennett Building is a cast iron office building.

As for steel frame buildings, Lord & Taylor’s Fifth Avenue and 19th Street location in the early 1900s occupied the building type most often associated with manufacturing and industry (below). Its generous ceiling heights distinguish it from the manufacturing loft buildings further down the Avenue. Note the mansard roof of Arnold Constable & Co. extending from Broadway, and the transformations of the brownstone homes.

When it comes to the city that moved uptown, the purpose of a building is the main arbiter of sense and meaning.

The fate of buildings and neighborhoods over time, and how their original use changed like hermit crabs change shells, are additional chapters to an already inordinate story.

Use informs the city

While the different combinations of buildings tell the story of a neighborhood, it’s the different combinations of buildings across a dozen different Manhattan neighborhoods that tell the story of the whole city.

The post City Hall: Epicenter, described how the Lower East Side, Financial District and Tribeca developed as tenements, finance-related buildings, and warehouses. Those neighborhoods are relatively easy to decipher; it makes it even easier that they all share a history of just three earlier types of homes: Georgian, Federal, and Greek Revival.

Between City Hall and Central Park, however, the built environment was more complex and class-based. Rather than two, three layers of an attenuated history, and faster moving parts, moved through.

The city’s space on the palimpsest stretches through a column on the grid, between 3rd and 8th Avenues. It developed like an armature up Broadway and Fifth Avenue, and parts of Sixth, across geography and the grid.

From the 30,000 foot level, the precise location of a home, store, hotel, office or factory building, whether on the same block or around the corner, is not as important as the class-based compositions frozen across a dozens of Manhattan neighborhoods. Nineteenth century modes of life, incompatible as they were on an island like Manhattan, passed over and absorbed one another.

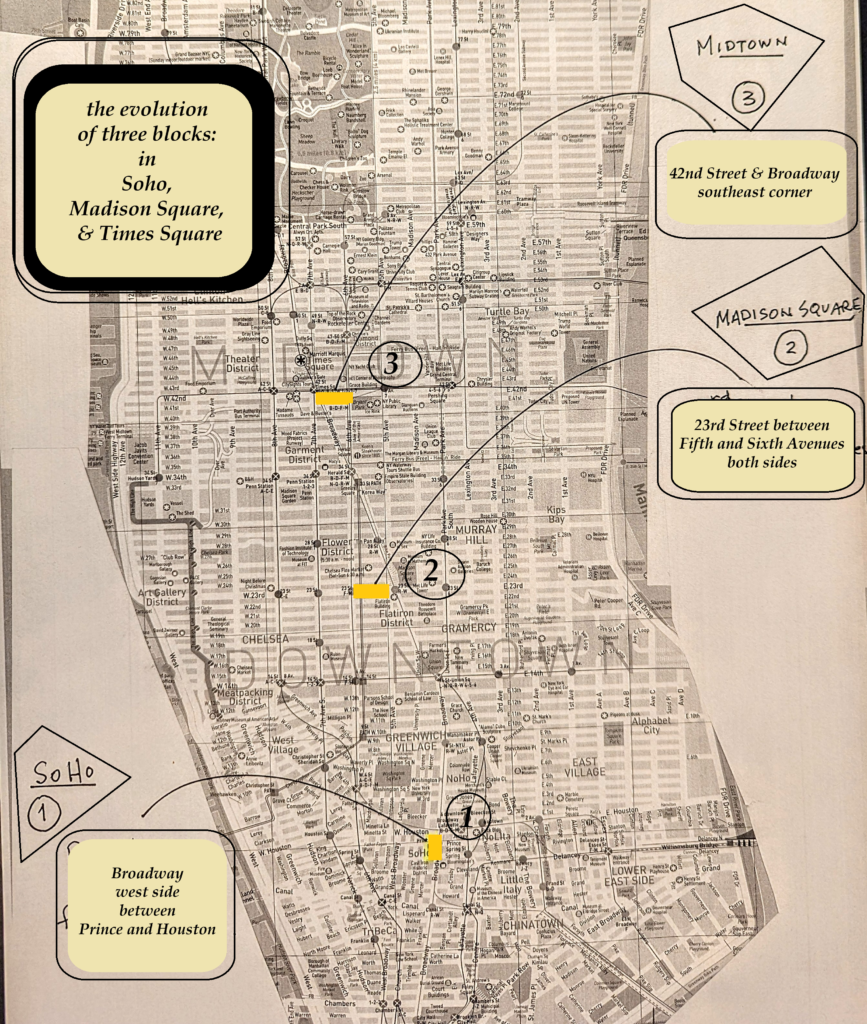

Below are three “sample” blocks, ascending from downtown to uptown in SoHo, Madison Square, and Times Square, about a mile or so apart. In each block can be seen the developmental algorithm: live, play and work, through ever-larger buildings of residential, cultural, and commercial business capacities.

- SoHo

Broadway, west side. between Prince and Houston

Climbing up from Canal Street, Broadway levels upon reaching Houston and entering the Greenwich Village.

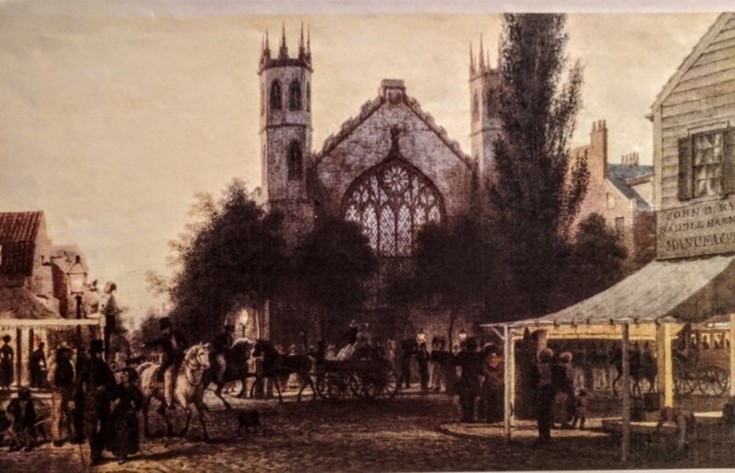

St. Thomas Episcopal Church stood at the crest of the hill in 1826 where the Cable Building stands today on the northwest corner of Broadway and Houston Street.

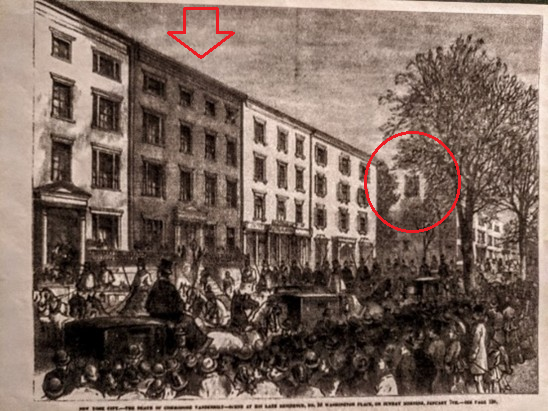

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (below, left) recorded the activity in front of his home during John Jacob Astor’s funeral in 1848. The block shows some of the city’s finest Greek Revival of the time. Astor’s home furthest to the left in the image. The pinnacled tower of St. Thomas is visible through the tree!

Astor’s neighbor at 589 Broadway was the residence of Judah Hammond (1832), the shaded facade in the image. The building continues in the streetwall today…

The four buildings to the right (uptown side) of the Hammond house were fashionable retail stores from 1859, ’60, ’66, and ’67. The steel frame loft building on the opposite side, though, is from 1897, and housed high end garment trade manufacturers and wholesalers at a time when Broadway functioned like one big convention center for the garment trade.

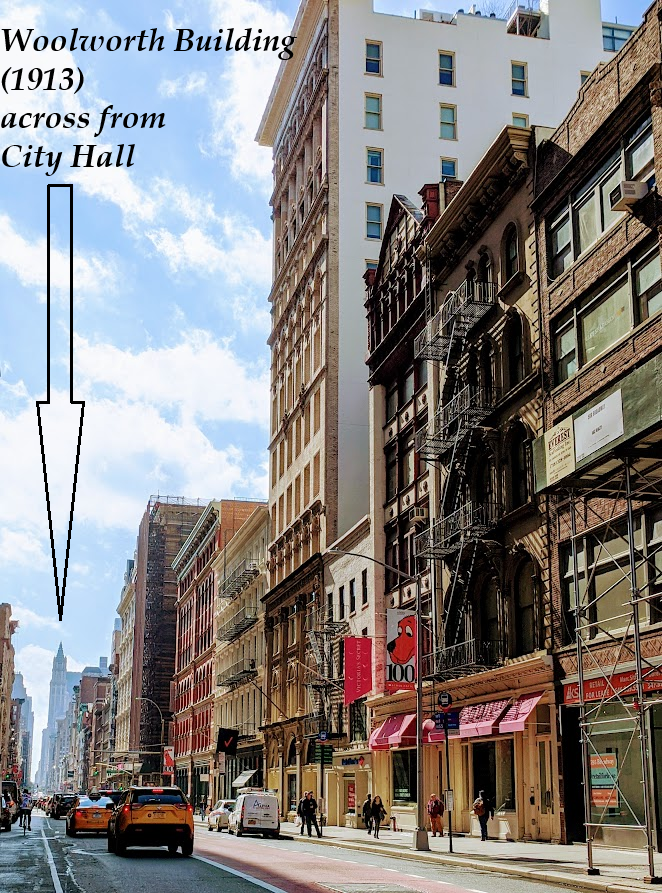

While Astor’s children moved further away to Colonnade Row (now Astor Place), Astor’s decision to move to the top of the hill becomes clear from Houston Street where he and his neighbors could see across the city from their porches. Broadway slopes down to Canal Street and in the distance, the Woolworth Building marks where the Astor’s moved from in the early 1830s.

The people on the sidewalk show the imposing size of the early homes.

From elegant homes of the upper class in the 1830s to refined retail storefronts (and light manufacturing upstairs), and ultimately to large-scale wholesale operations, the uptown progression of Manhattan followed a distinct pattern. This journey—from sacred spaces to more utilitarian purposes—often featured evermore stunningly ornate buildings, transitioning from residential to commercial culture and commercial business.

2. Madison Square

23rd Street, between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, both sides

The south side of 23rd Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues show the upper class residential history in heights, widths, and fenestration and brownstone facades on some. Edith Wharton’s family home has the trees on top.

1868 was a significant year in the city’s move uptown. That year, Arnold Constable & Co., an upper class shop, the Booth Theater, and the Grand Hotel opened along the radial roads of Broadway and 23rd Street about equidistant from the Fifth Avenue Hotel (1859) in the heart of Madison Square.

The Booth Theater was part of the block we’re following below.

The Booth Theater opened on the southeast corner of Sixth and 23rd Street in 1869. This view, from the other end of the block, was before the elevated train of 1879. The residential history is still clearly visible in the rest of the block, including a church.

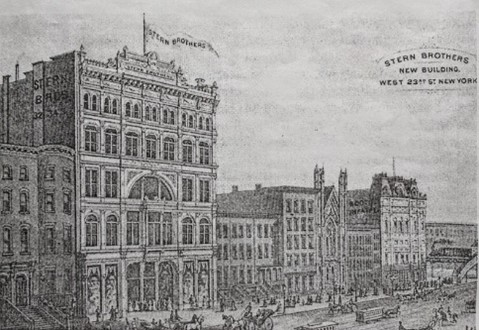

Stern Brothers’ (1878) re-worked the block with a cast-iron palace, and expanded over time, and is today Home Depot. The Booth theater and the elevated train are seen at the end of the block in the still largely residential neighborhood.

The Flatiron Building (1902) stands in Madison Square in the image above; Stern Brothers has expanded, and the church site has been fully redeveloped as fashionable clothing stores. The corner of the Booth Theater (converted to retail after the Depression of 1873) is visible, as is some of the earlier residential history in the facades of the upper floors of some of the re-worked homes.

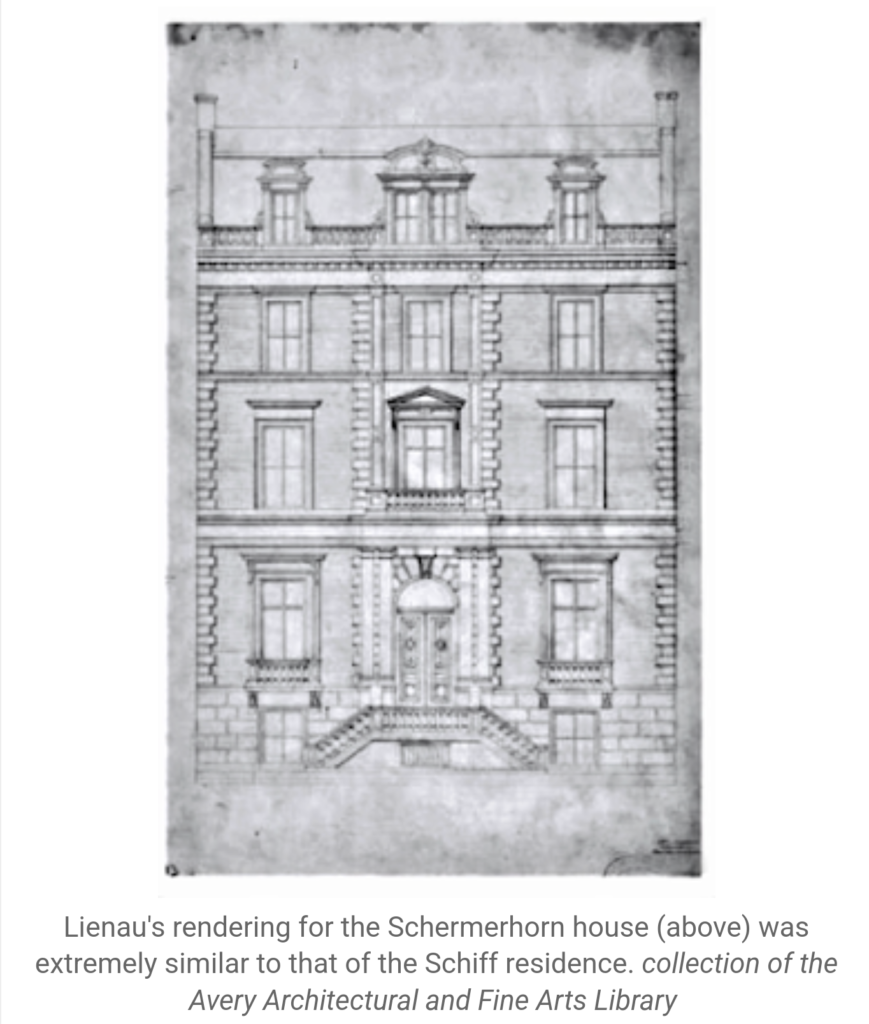

On the opposite side of the street, a sign for the Eden Musee (1883) is visible mid-way down the block. The rest of the images show the transformation of the Schermerhorn mansion (1856, Lineau) as the neighbor of the wax museum.

The Schermerhorns were related to the Astors, who lived around the corner, up Fifth Avenue. The building remained a family residence until the early 1900s, after which it was developed as a fine commercial loft building.

Many Manhattan blocks contain a triplet of buildings in the order of: residential, commercial culture, commercial business.

Finally, this is quick look at a postcard of 42nd Street in Times Square.

3. Midtown (42nd Street and Broadway, from southeast corner)

The smaller buildings with three windows across, if not single family homes, likely functioned as residential in some capacity when first erected around the mid-19th century. The Knickerbocker Hotel (1904) is visible to right, and the Bush Tower (1918), a showroom and buyers club brainchild of a pier operator, stands tallest as the main feature of the image.

From the Sacred to the Profane in ever larger buildings

It was an uptown flow of construction on three fronts in occupational descent from the sacred to the profane. Profane as in secular and mundane; building occupancy and redevelopment went from home to hotel to office, from church to theater to factory. Fine restaurants became less fine (Delmonicos became St. Martin’s Cafe); theaters changed programs for more popular fare; hotels catered to more a professional, rather than a leisure class, as the city moved uptown.

Sometimes the process cycled through the same building; a private home of 20 years might become a retail shop, like a tailor or florist, and 25 years later a wholesaler might be operating within the walls of an old home. More often than not though, newer, larger buildings replaced smaller ones in grand, often flamboyant styles for evermore mundane purposes.

An occupational descent progressed from the sacred to profane in ever larger buildings through the center of Manhattan.

Select bibliography

Burrows, Edwin G. & Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, Oxford University Press, 1999.

Henderson, Mary, The City & the Theratre, James T. white, 1973.

Lockwood, Charles, Manhattan Moves Uptown, Houghton Mifflin, 1976.

Stern, Mellins, and Fishman, New York 1880: Architecture and Urbanism in the Gilded Age, Montacelli Press, 1999.

Stern, Gilmartin, Mellins, New York 1930: Architecture and Urbanisn between the World Wars, Rozzoli, 1987.

White, Norval, New York: A Physical History, Athenuem, 1987.

Internet Resources

Daytonian in Manhattan, Tom Miller

The New York Historical (formerly The New York Historical Society)