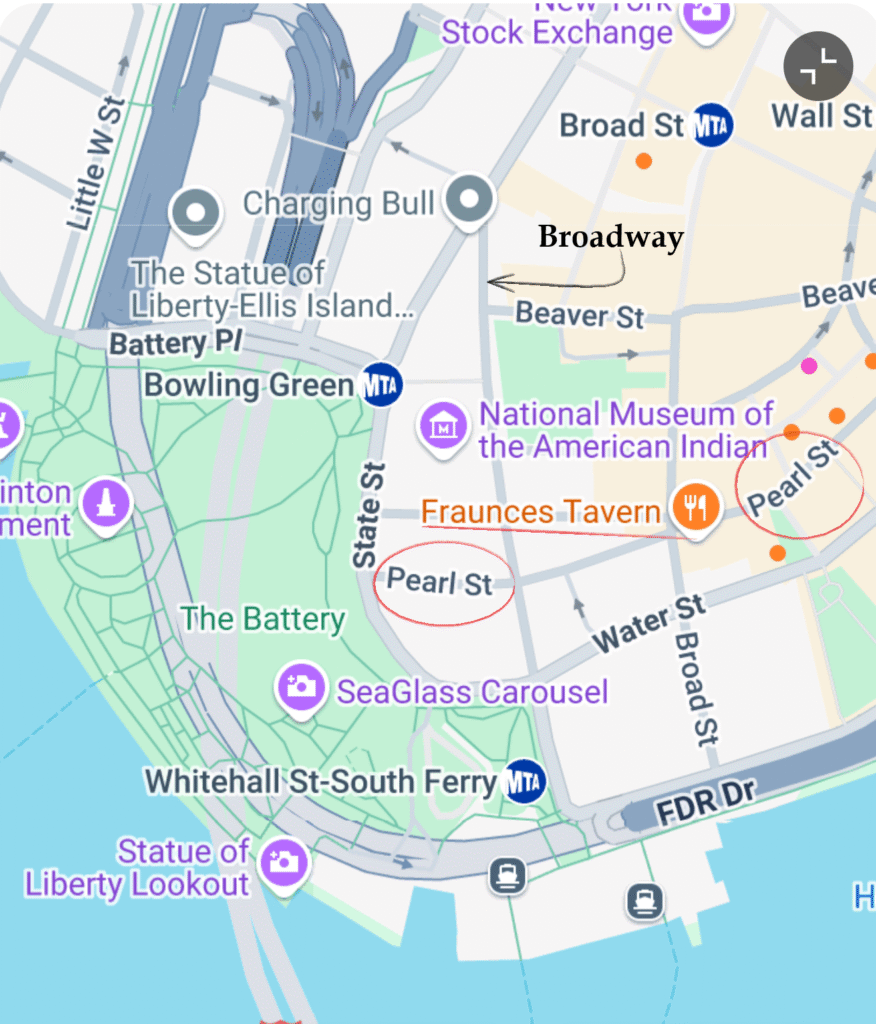

Pearl street derives its name from the shell middens left by Manhattan’s original Lenape inhabitants at the island’s southern tip. Initially, it spanned a single block between State Street and Broadway.

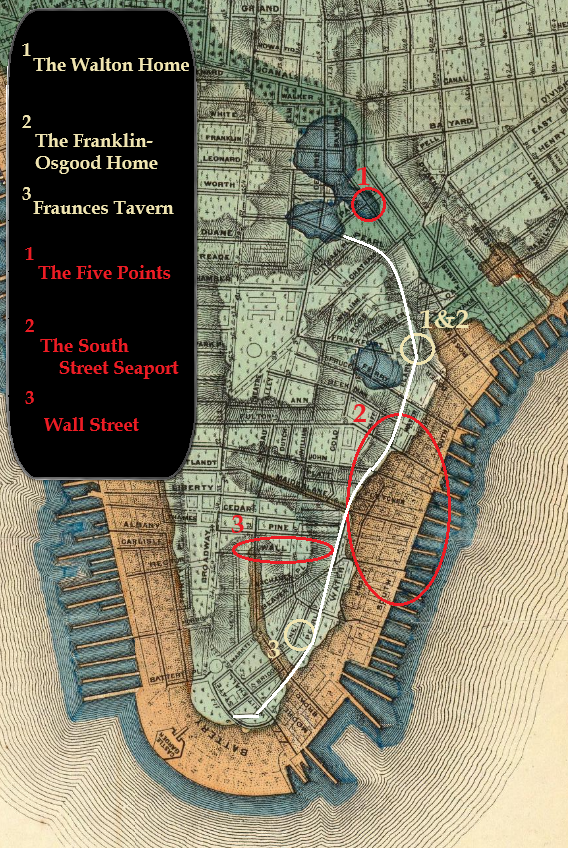

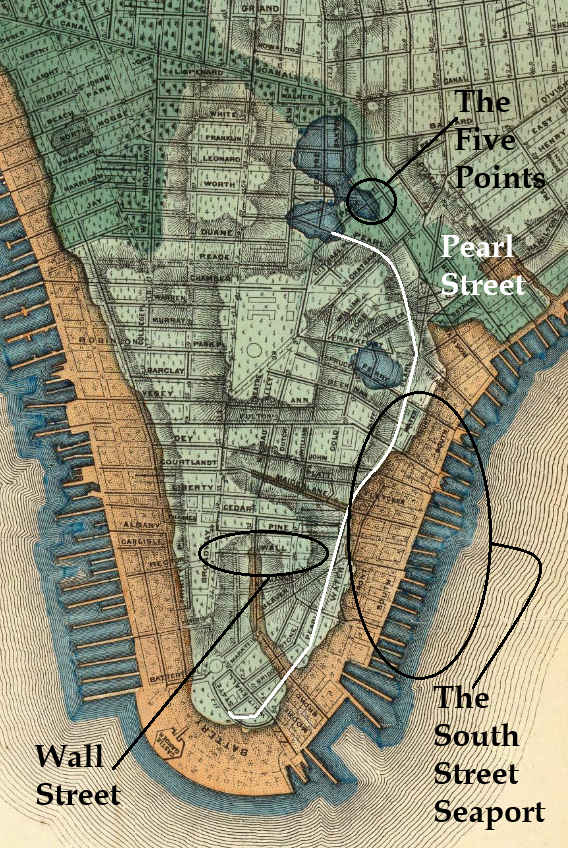

The Bradford Map (below) shows the 1728 Colonial city with Pearl Street at the bottom of the island along with the streets that will later adopt its name, Dock and Queen, circled in red; Wall Street is also circled.

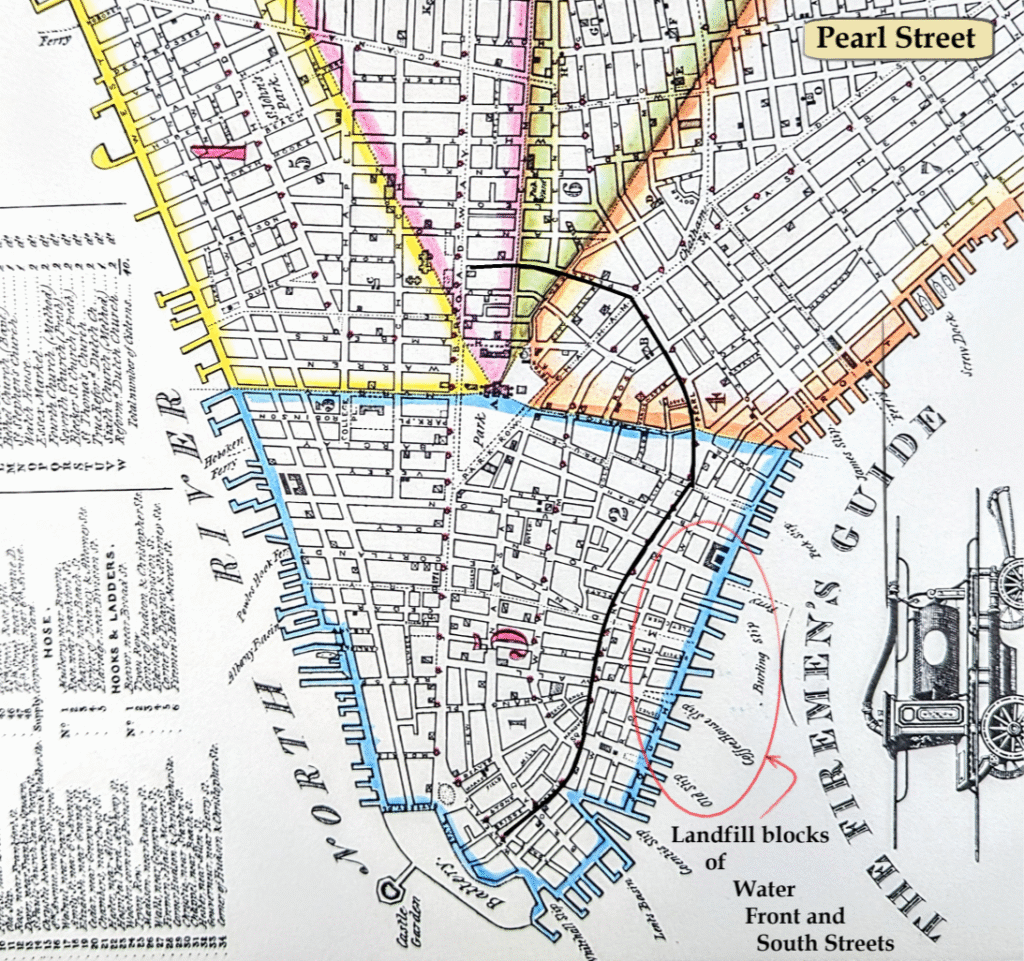

Note the South Street Seaport comprising the landfill blocks of Water, Front, and South Streets does not yet exist.

James-Lyne/Bradford Map, 1728

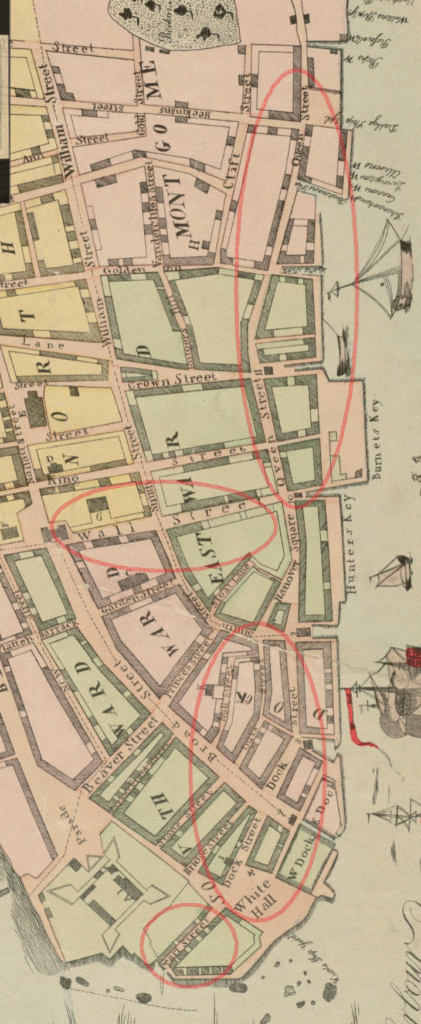

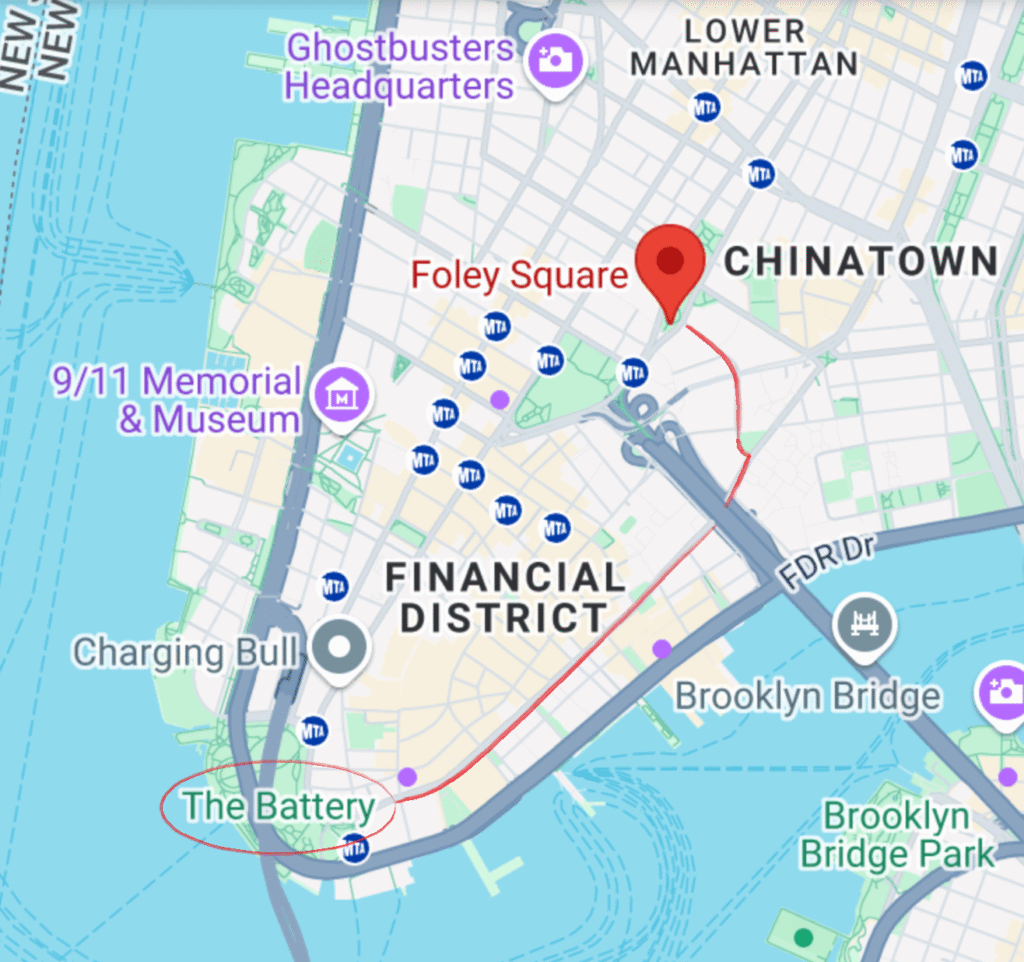

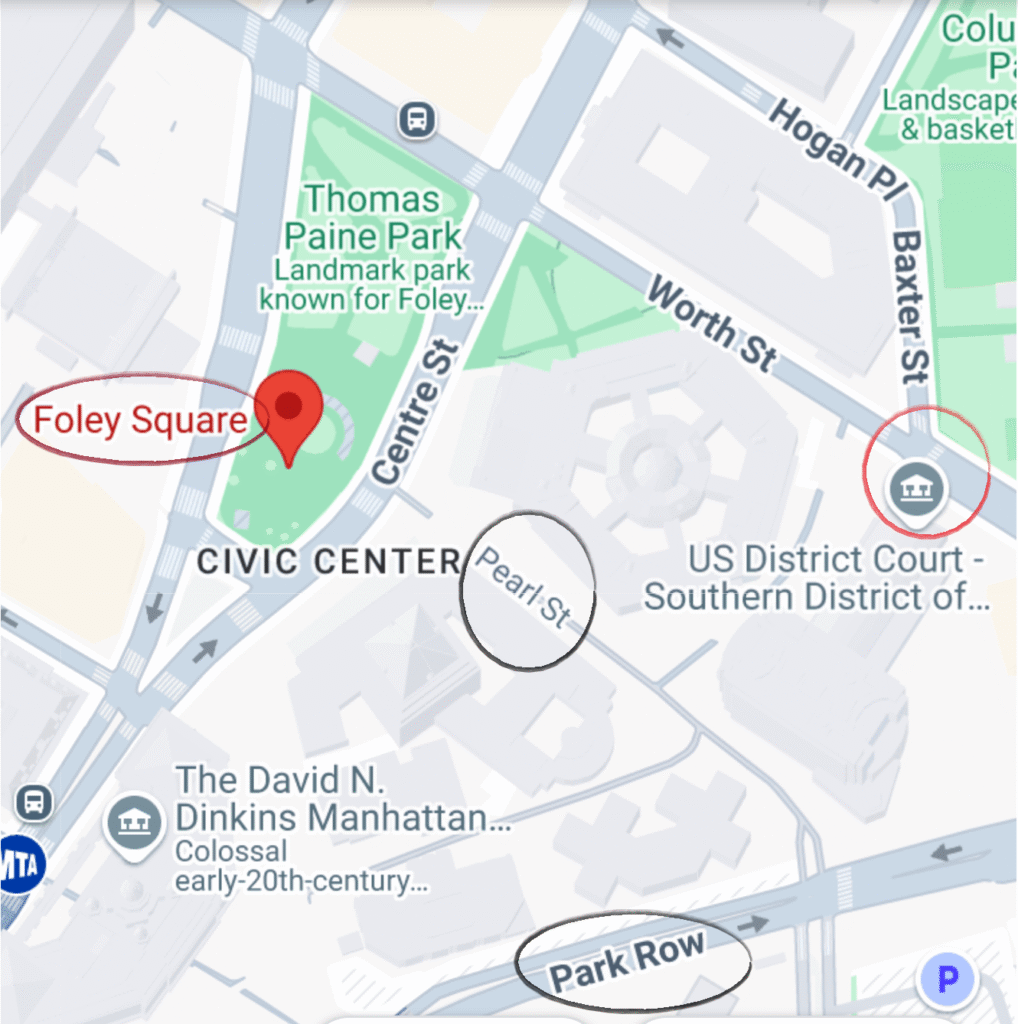

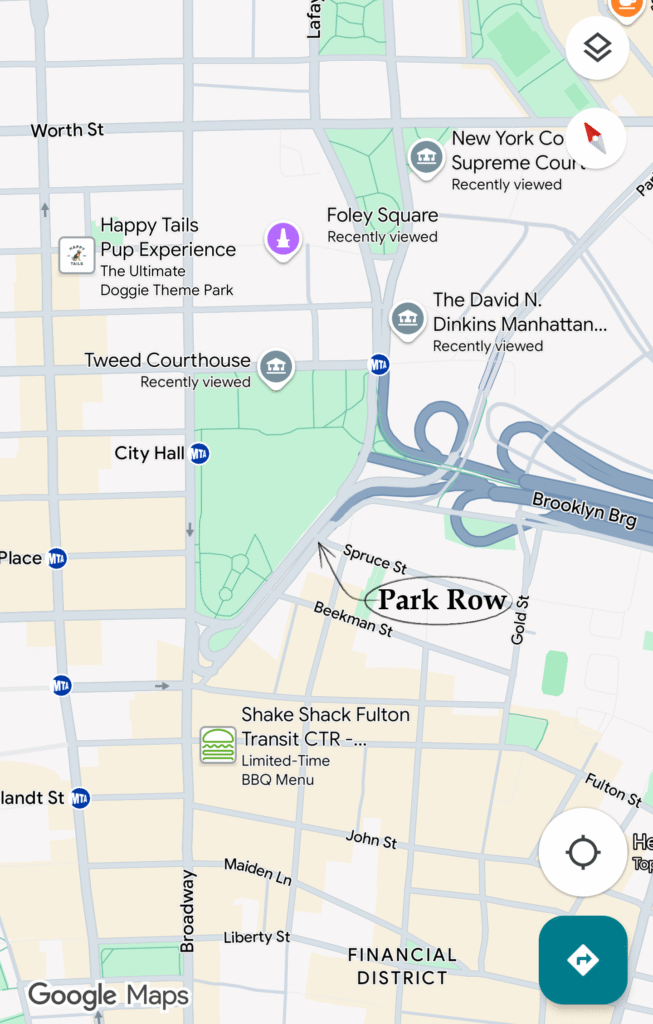

Over time, Pearl Street extended its reach a mile uptown, stretching all the way to Foley Square and the Civic Center, the site of the historic Collect Pond, north of City Hall. The maps below show Pearl Street’s path from The Battery to Foley Square.

Map of The Battery, NY. Google Maps. 6/5/25

Map of Lower Manhattan, Foley Square, NY. Google Maps. 6/5/25

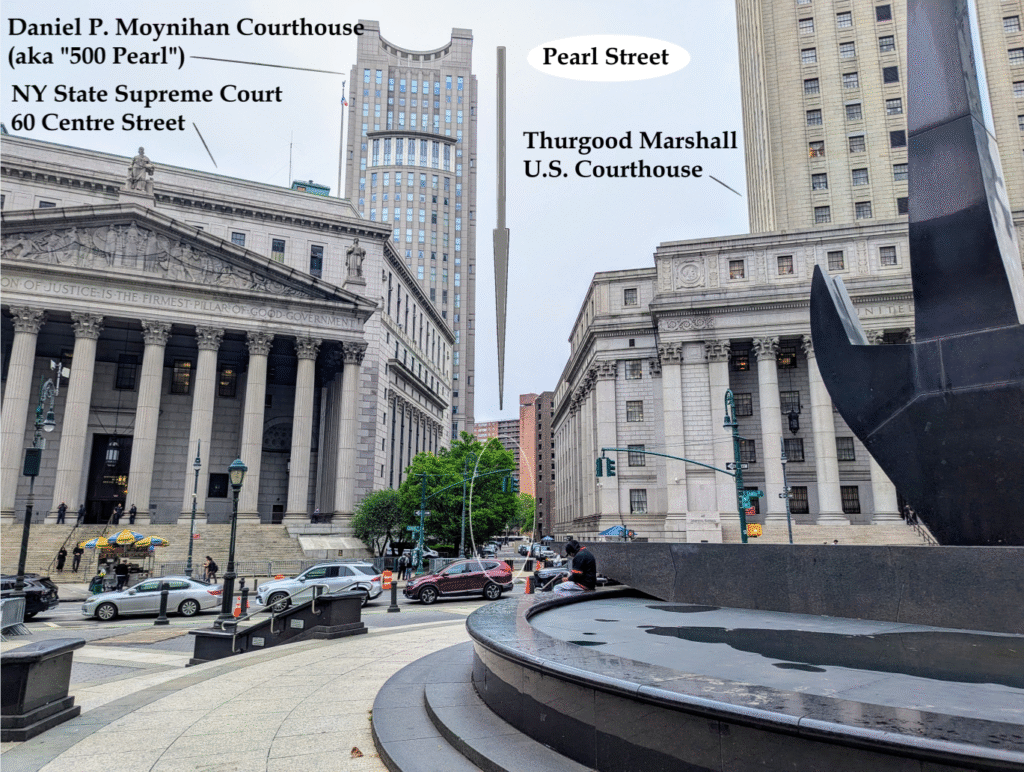

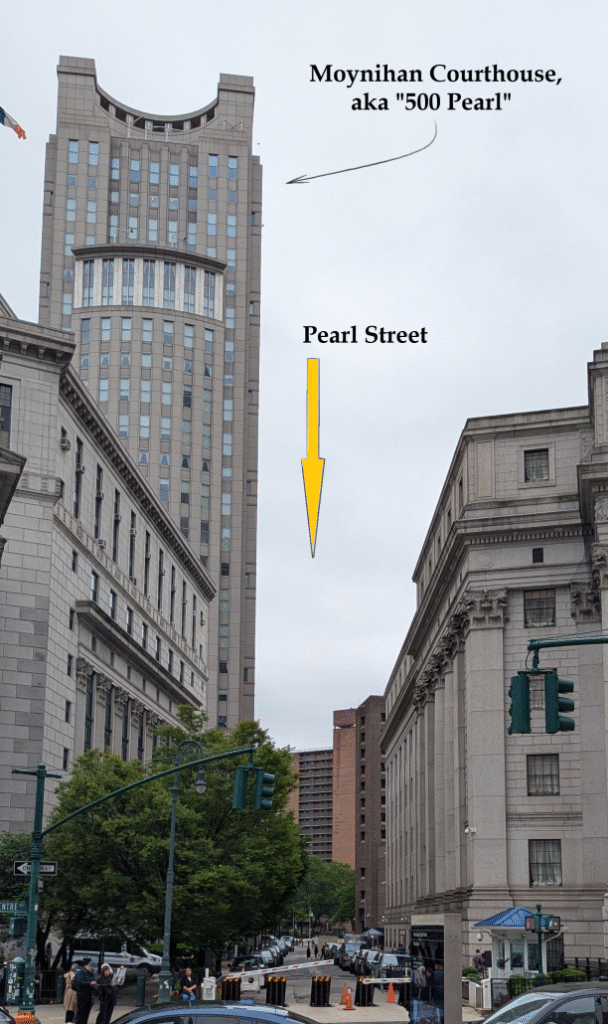

Pearl Street ends today in Foley Square alongside 60 Centre Street, the New York County Courthouse (Lowell, 1927), with its familiar steps from film and television.

Pearl Street ends today between two Neoclassical landmarks. The other is the Thurgood Marshall US Courthouse, 40 Centre Street (Gilbert, 1936).

The towering post-modern building is the Daniel Patrick Moynihan Courthouse, aka “500 Pearl” (Fox, 1996), frequent venue of high-profile cases brought by the Southern District of New York.

Pearl Street is a pedestrian passage here, for official vehicles only.

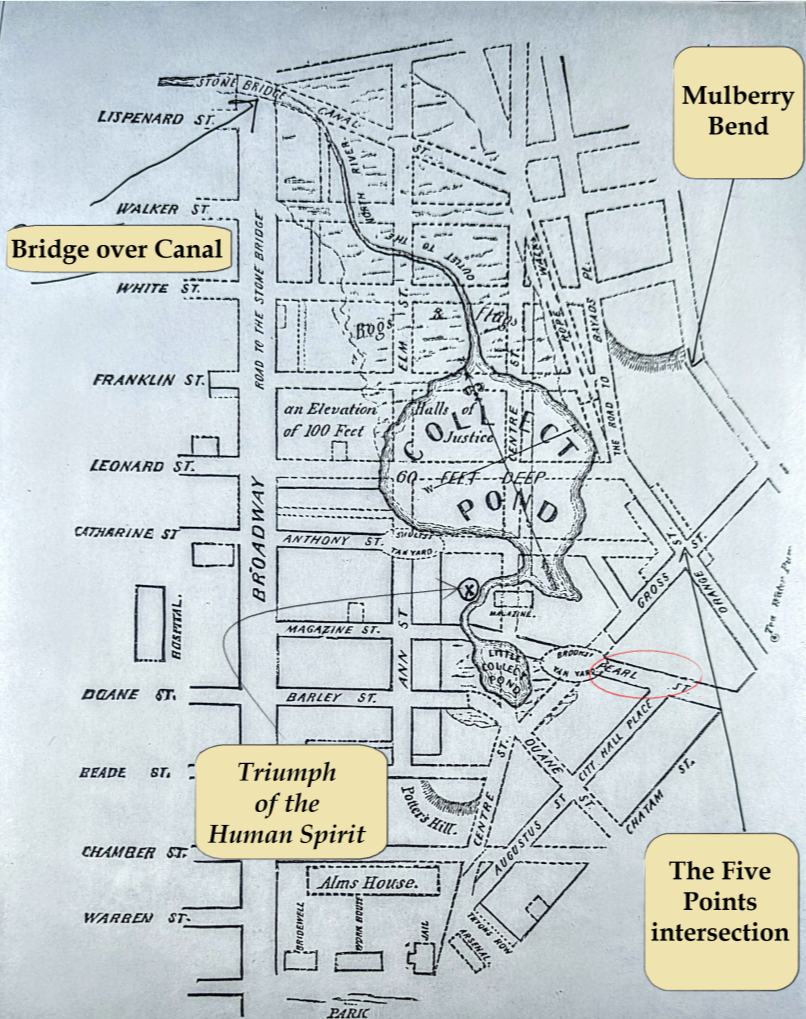

Much of Foley Square sits atop the site of the old Collect Pond. Lorenzo Pace’s, Triumph of the Human Spirit is central to the plaza, a tribute to the African Burial Ground nearby the lake’s former shoreline.

The sculpture is over the site of a small island once used for storing munitions (a magazine). It was also the execution site of 13 as retribution for the Slave Insurrection of 1741.

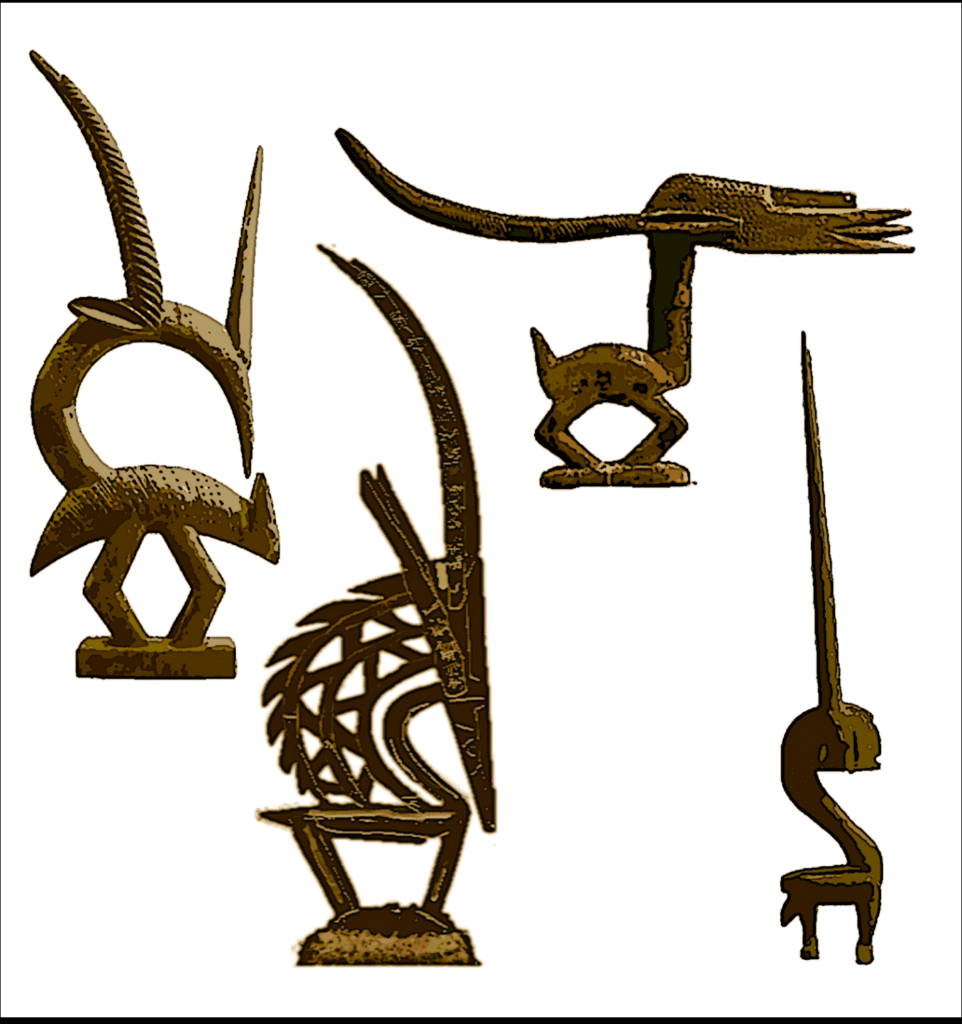

Four types of Chiwara masks (wikipedia)

Inspired by the Chiwara art of the Bambara people from Mali, West Africa, Triumph of the Human Spirit draws upon traditional antelope motifs used in ceremonial masks and figurines.

The map below shows the Collect Pond from As You Pass By, with Pearl Street circled in red; The Five Points and Mulberry Bend were nearby neighborhoods.

As You Pass By, Map of the Collect.

Today’s Pearl Street once terminated at the Collect Pond.

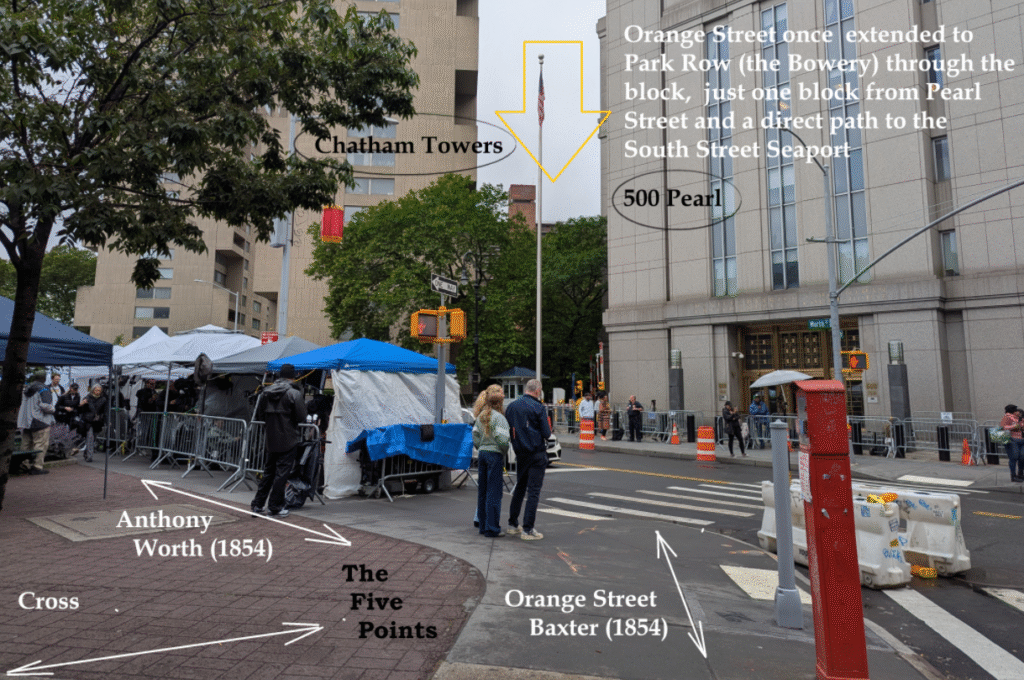

Worth Street is one block north of Pearl and was one of the streets that made the notorious intersection for which The Five Points neighborhood was named, just around the corner from today’s Foley Square.

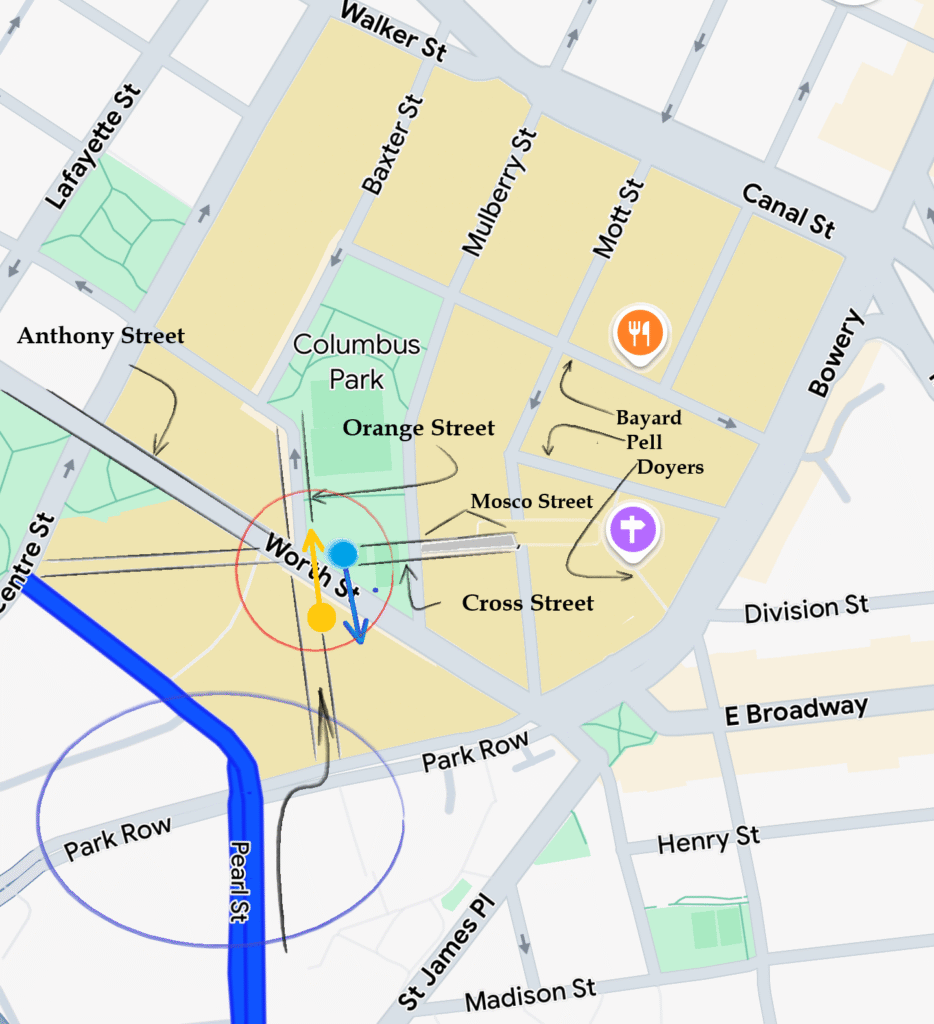

Circled in red below, at the intersection of Worth and Baxter Streets at the southwest corner of Columbus Park were the “five points,” directly across from the entrance of 500 Pearl.

Map of The Civic Center, NY. Google Maps. 6/25

The Worth Street entrance for 500 Pearl offers the shortest distance between a waiting Escalade and the courthouse, naturally paparazzi often camp out there.

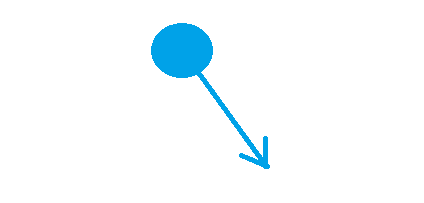

In a remarkable historical resonance, where the paparazzi set up today is the same spot past documentarians immortalized scenes of The Five Points, only their orientation was reversed, and pointed cameras and positioned easels facing the opposite direction.

The two points of view are shown below, two hundred years apart.

(below, left) People stand with their backs to the scene of The Five Points in 1827 (below, right).

The configuration of streets comprising the “five points” is highlighted in black and circled in red on the map below. Notice a section of Worth Street was not part of the original five points.

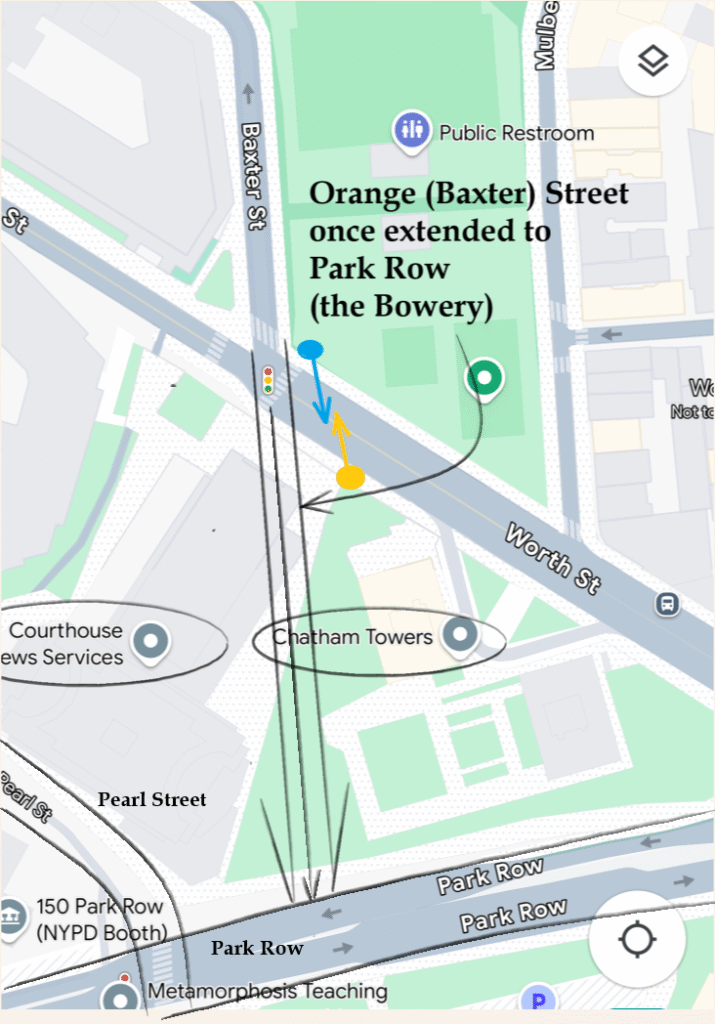

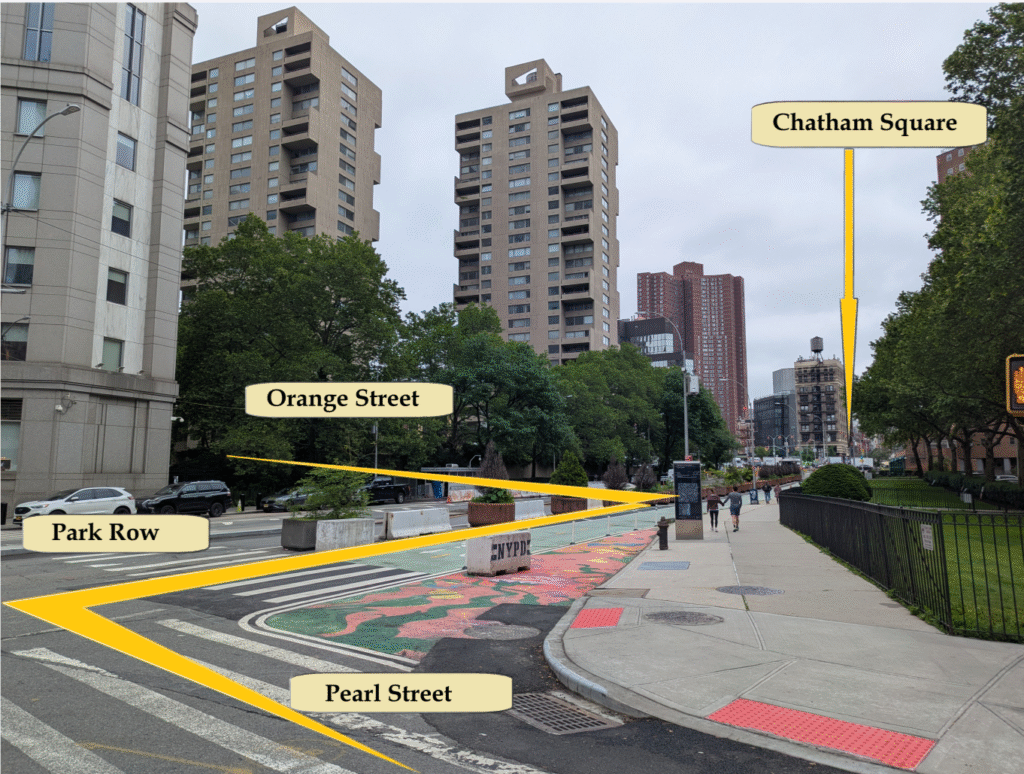

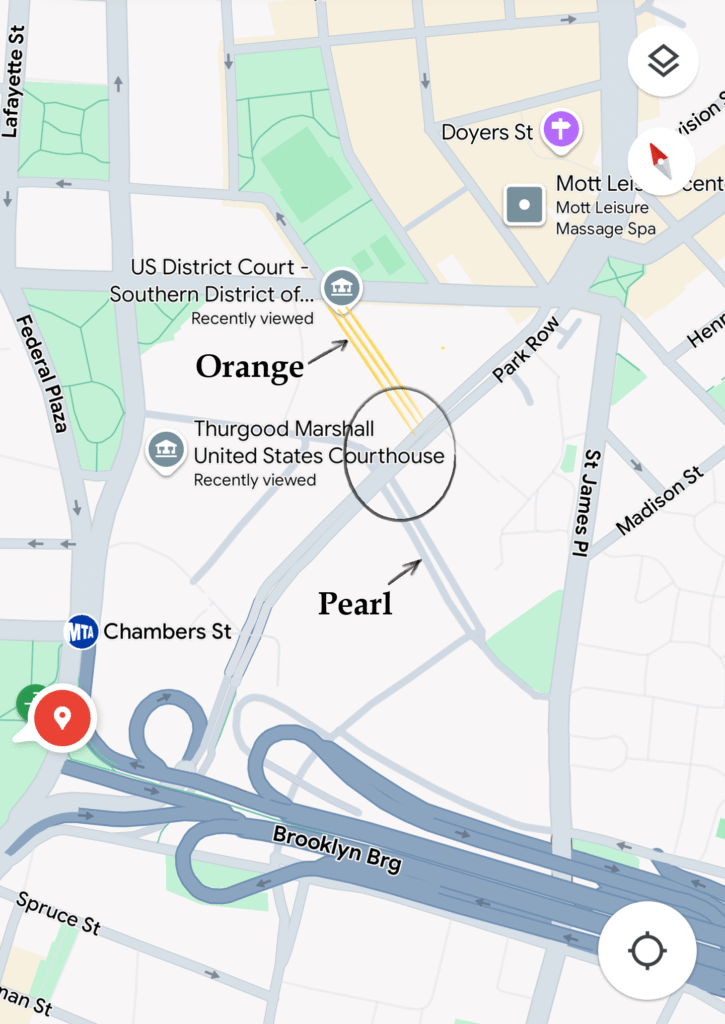

Orange Street (today’s Baxter), once extended through the block to Park Row, a short distance from Pearl Street (blue circle). The arrow shows the zig-zag a traveler would have taken from Pearl Street to reach the city’s most densely packed blocks of brothels from the the 1820s – 1850s.

Map of The Civic Center and Chinatown, NY. Google Maps. 6/25

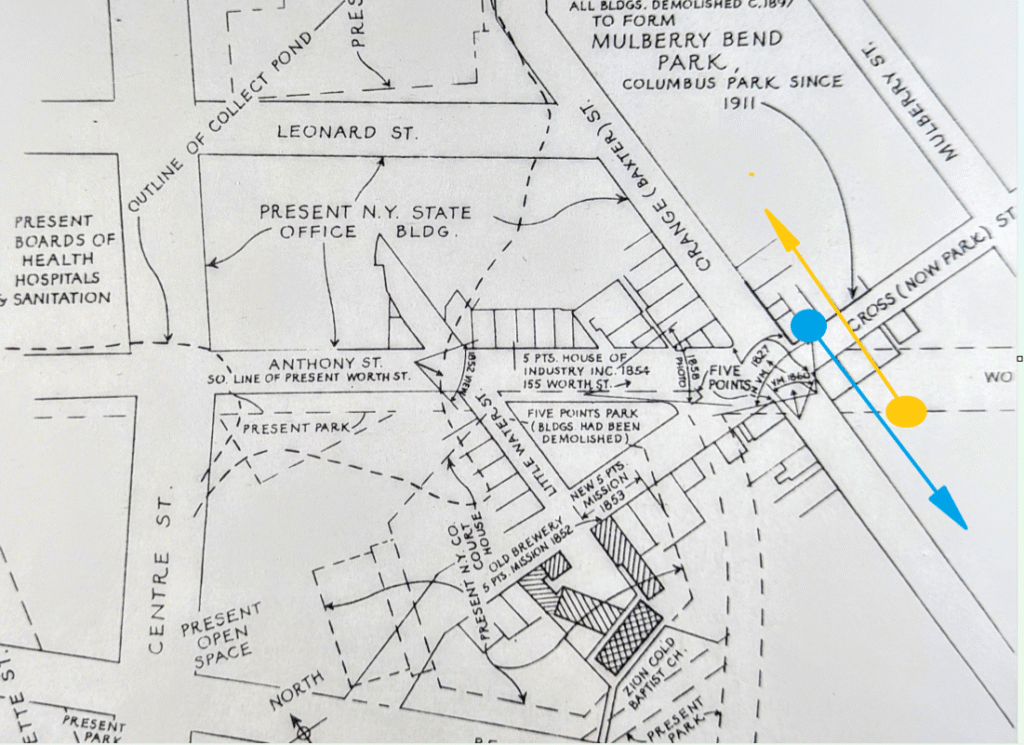

The map below from As You Pass By includes a lot of detail and outlines the historic Five Points intersection, with renamed and altered streets.

Cross Street, the first to traverse the area, now exists only as Mosco Street, a short link between Mulberry and Mott.

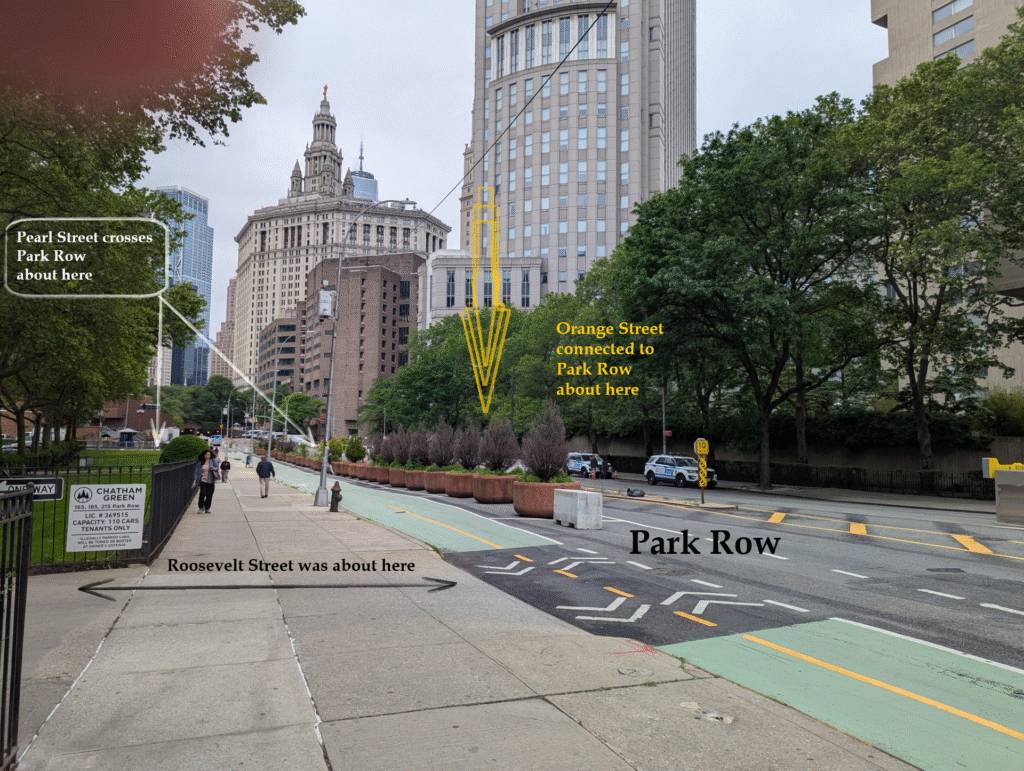

Baxter Street (formerly Orange) once extended below Worth (formerly Anthony), connecting to Park Row.

The Five Points emerged in 1817 when Worth intersected Cross and Orange Streets. By the 1860s, Worth extended to the Bowery, marking the end of the neighborhood’s notorious era.

Orange Street once extended through the block, linking the infamous heart of The Five Points to Park Row, the main thoroughfare leading uptown to the Bowery.

The view from the Park Row side shows the approximate spot Orange Street once connected to Park Row.

This is how a traveler could navigate from Pearl Street to Orange Street (and The Five Points) along Park Row in the past.

Here’s the view looking back (downtown) from the high ground of Chatham Square.

Like many old streets in New York, Park Row had a few identities, including The High Road to Boston, the Bowery, Chatham Row, and others.

Park Row is one of the three sides of City Hall Park, with Chambers and Broadway; it was a more important road when the Bowery, not Broadway, was the main uptown thoroughfare.

Though both Pearl Street and Park Row have been re-worked and altered from their original roadbeds through different periods of development, where they intersect today is near exact to where they met in the past.

South of the Brooklyn Bridge, Pearl Street makes sense insofar as it follows the waterfront, albeit several blocks inland due to the landfill blocks of Water, Front and South Streets—the blocks of the South Street Seaport.

What’s interesting is that Pearl Street ends in the middle of the island. Even more curious (maybe stunning) is its dramatic 90-degree turn between the South Street Seaport and Foley Square, a few blocks and a 5-10 minute walk. Above the Brooklyn Bridge Pearl Street disrupts every street pattern it touches. Its path is as much a relic and oddity as the curved, narrow blocks New Amsterdam.

The Fireman’s Guide, Published by P. Desobry, 1834.

That Pearl Street survives at all above the Brooklyn Bridge is a small miracle. While open to pedestrians, these blocks are utilitarian and non-descript driveways and parking spaces for official buildings, each a few degrees further west than the next.

An explanation for the peculiar route of upper Pearl Street can be found in the Viele map, a wonderful resource revealing the island’s original topography and the 1865 city.

The high ground beneath the triangle-shape of City Hall is clearly evident. Less noticeable, however, is the elevated ridge extending from City Hall’s northeastern edge, spiraling downward like a staircase toward the waterfront at Peck Slip, and New York’s early “Colonial aristocracy.”

Pearl Street does follow the old shoreline, insofar as a cross-island river valley once effectively cut the island in two.

Fed by underground springs, the fresh waters of the Collect Pond drained to the Hudson and the East Rivers creating a near water-level wetland ecosystem that stretched from river to river.

It’s easy to see how Canal Street once drained to the Hudson. More difficult to see and imagine in the streetscape is how the Collect drained to the East River. In fact, the Old Wreck was the river that started around Orange Street and drained along the path of Roosevelt Street, or, on some maps, made a serpentine path across today’s Roosevelt, James and Oliver Streets.

Pearl Street followed different kinds of shoreline. Walking up along the East River, upon reaching the Old Wreck, travelers were naturally guided inland.

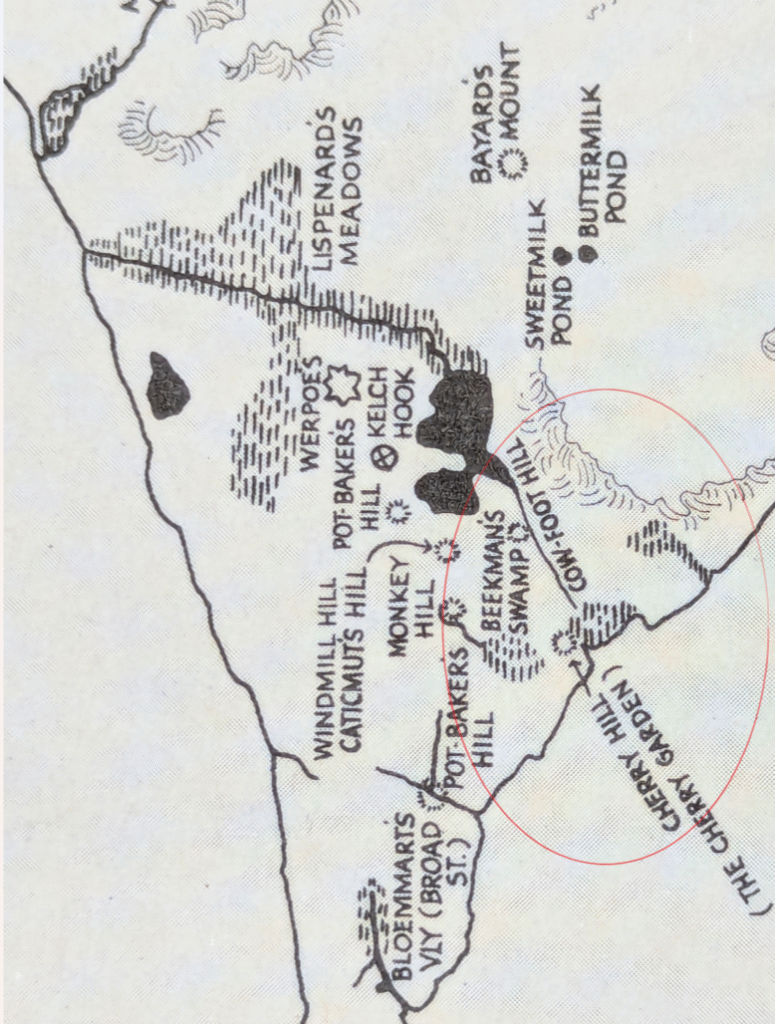

Pearl Street and the Five Points (and a Kissing Bridge to be discussed in the next post) are noted on the map below.

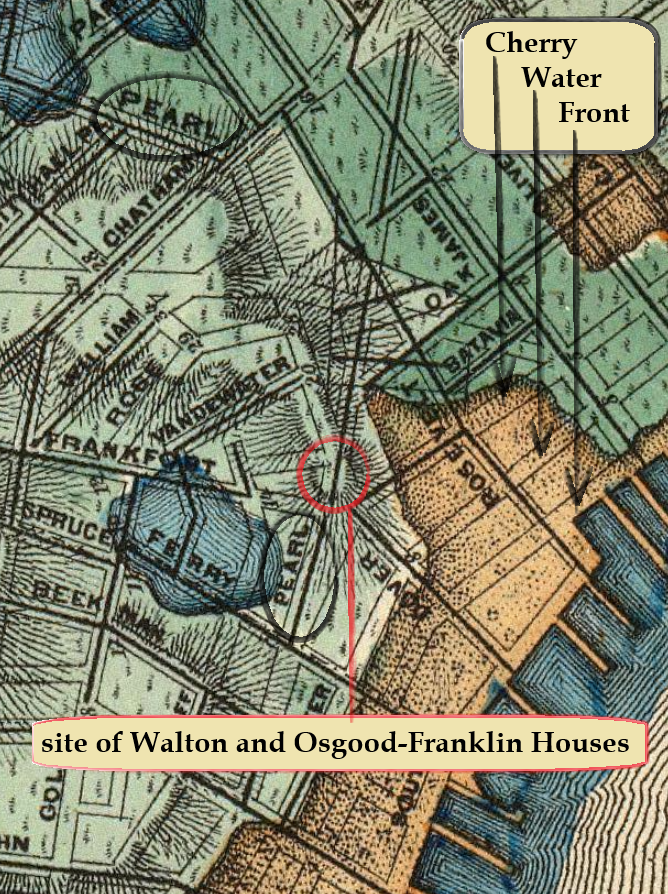

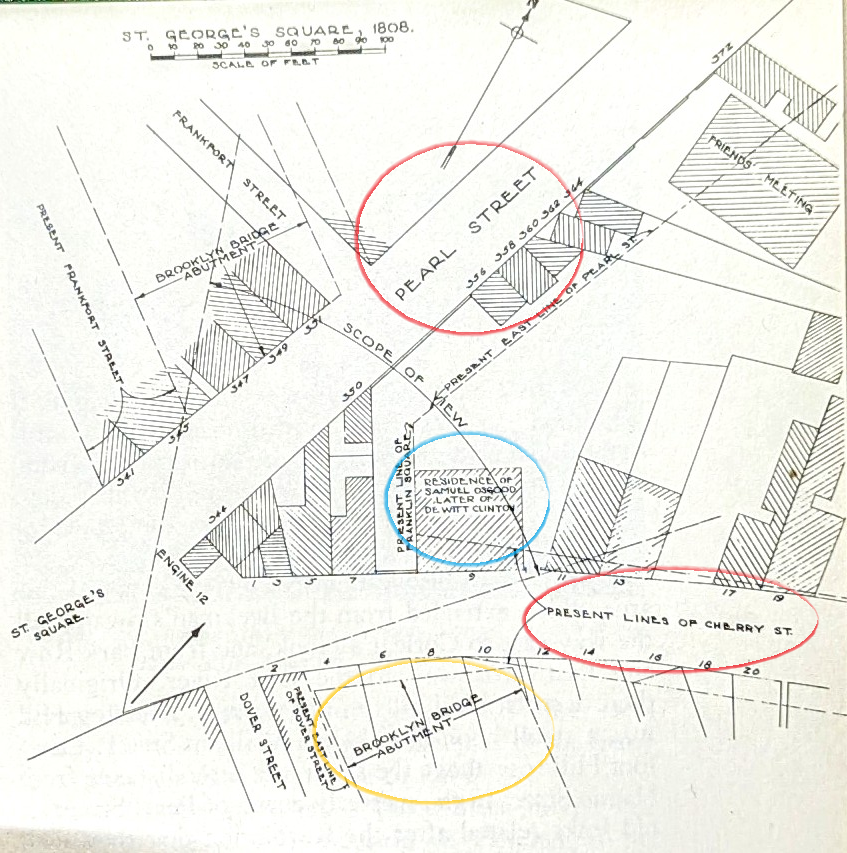

The descending ridge straddled the Collect Pond (and the Old Wreck) on one side, and Beekman’s Swamp on the other, ending at a patch of high ground known as St. George’s Square, and renamed Franklin Square in 1817. This was where Pearl Street diverted inland to follow the course of the Old Wreck back to the Collect Pond, and Cherry Street continued (across some landfill) as the shoreline road following the East River.

“Colonial aristocracy” settled this hillock near the East River, including two buildings that played significant roles in American History, the Walton House and the Franklin-Osgood House.

With Fraunces Tavern, the Walton and Franklin-Osgood homes–all on Pearl Street–were chapter books of American history in architectural form.

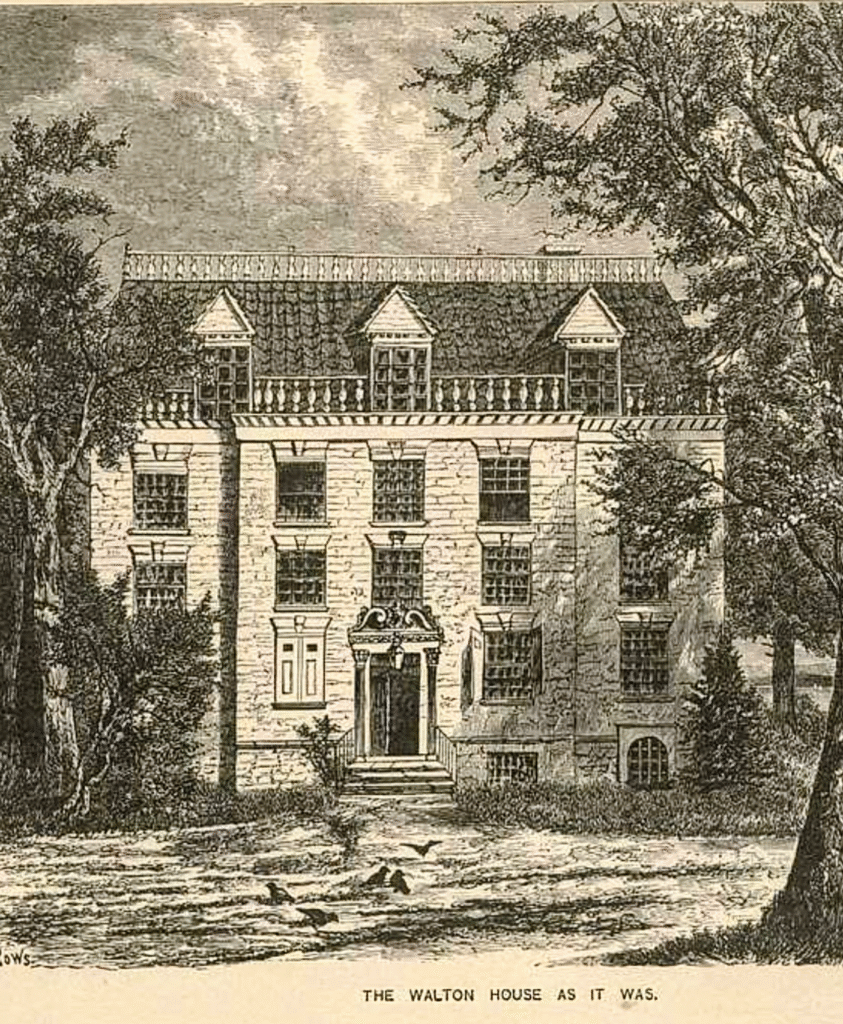

The Walton House, 324-326 Pearl Street (1754-1881)

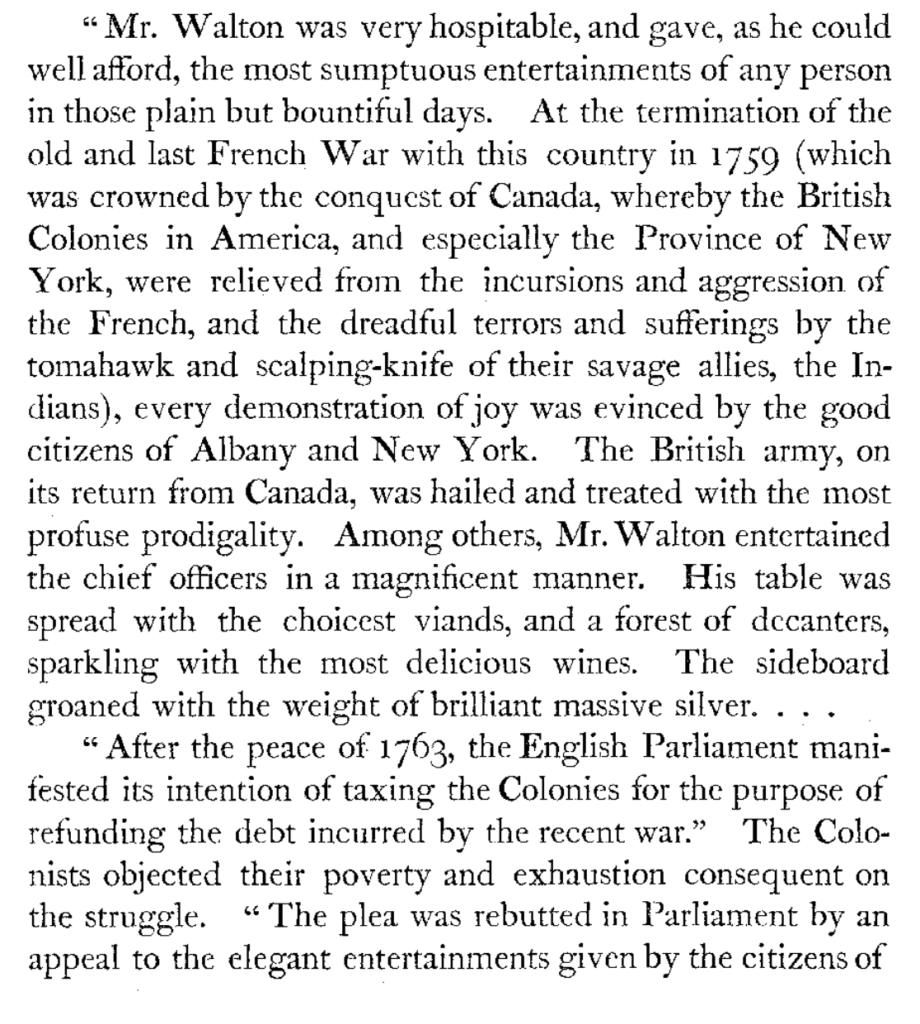

Built in the 1750s on the south side of Pearl Street by William Walton, son of a shipbuilder and trader, the home inadvertently helped start the Revolutionary War.

As You Pass By says “At Pearl Street, a few doors from Dover, stood ‘the most beautiful house in America,’ the Walton House. Constructed of yellow Holland brick, it had a double pitched roof covered with tiles and a double row of balustrades.”

The Colonial Records of the New York Chamber of Commerce 1768-1784 (J.F. Trow & Co) describes how the home was used to justify the Stamp Act, a stepping-stone to the Revolutionary War.

If you consider the celebratory dinner in 1759 the spark for what followed, the timeline unfolded over 30 years. The Franklin-Osgood House, a short walk from the Walton House and 20 years younger, served as George Washington’s residence as first president.

With Fraunces Tavern, where Washington stepped down as leader of the army only to return in an entirely different capacity after an election, Pearl Street holds a narrative unique in world history.

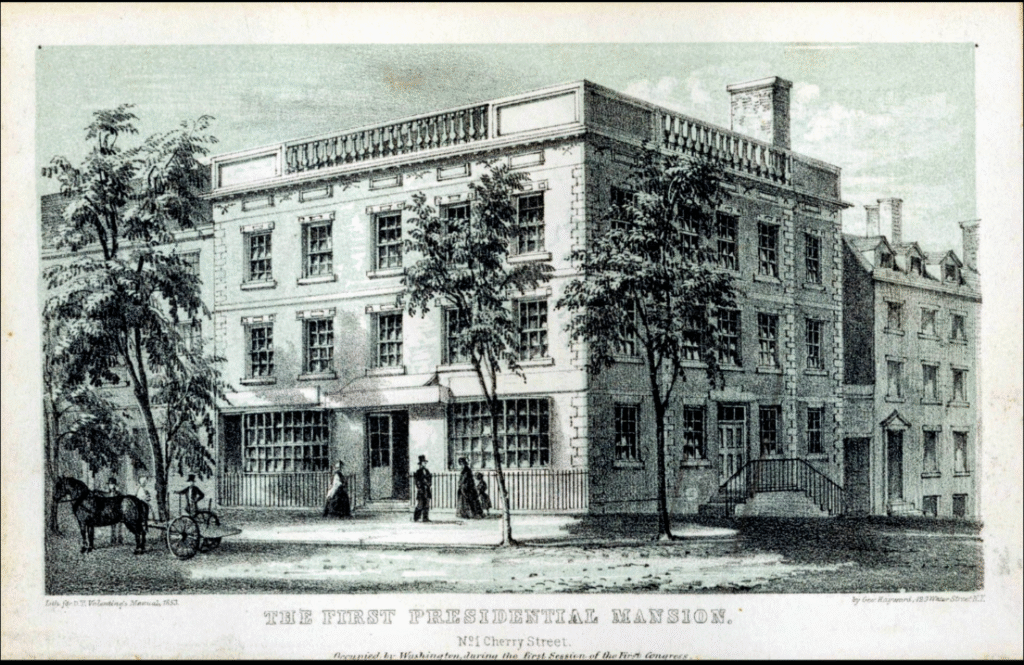

Franklin-Osgood House, 1 Cherry Street (1770-1856)

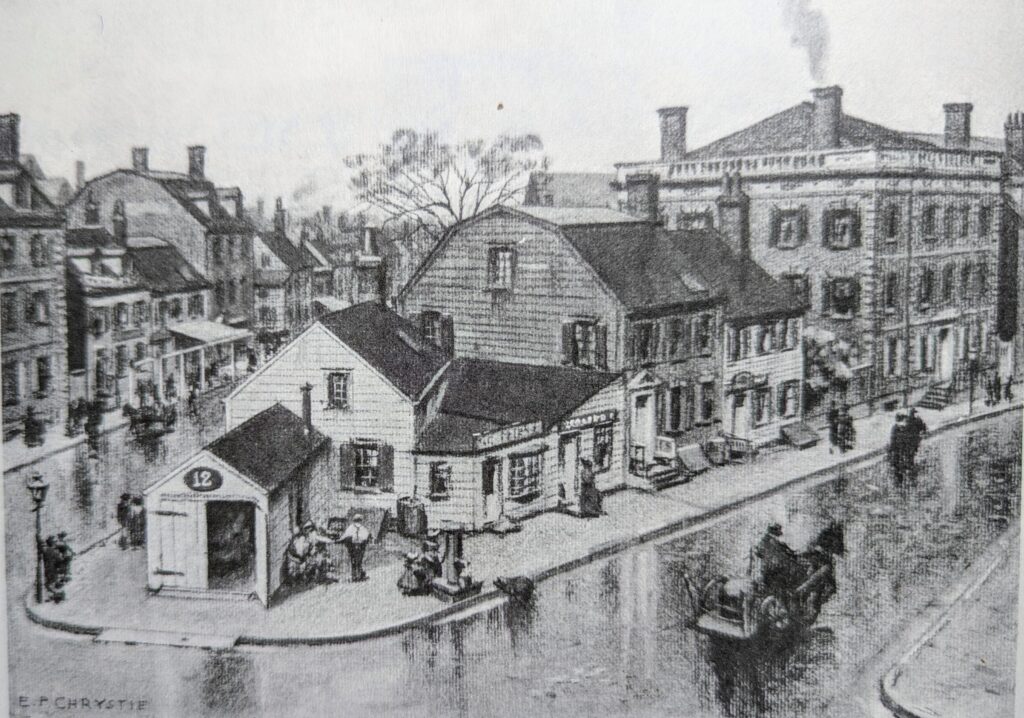

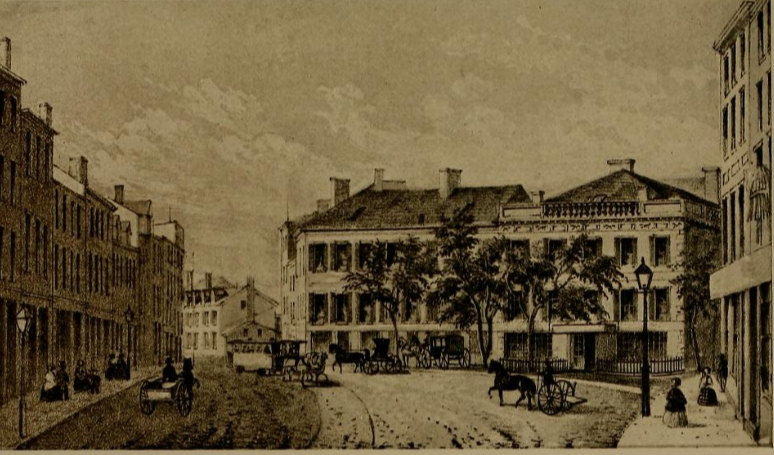

From As You Pass By, the image below shows the Franklin-Osgood house in St. George’s Square (1808) on Cherry Street; Pearl Street veers off to the left. Note the fire engine house on the corner.

Here’s the POV today, notice Dover Street to the right. The elevation of the area is still evident.

Early New York Houses, 1750-1900 (Pelletreau, 1900) shows Frankin Square after the corner buildings were removed and the neighrbohod was renamed. the Franklin-Osgood house is on the right, after the buildings on the corner, including the firehouse, had been removed by the city.

The author notes that “Pearl Street, north of this square, was, in ancient times, known as ‘the road that leads from Queen street to the fresh Water,'” possibly describing a path following the Old Wreck from the East River to its source at the Collect.

The rural map of Manhattan from As You Pass By (right) describes how “Cow-foot Hill rose above the swamps a little distance from Hague Street in the westerly curve of Pearl Street…”

Below is Hague Street on the Fireman’s Guide Map of New York, just above the junction of Pearl and Cherry Streets.

John Hill’s 1782 Map of New York depicts Cherry Street branching off Queen (Pearl) Street, with Cow Foot Hill rising above the swampy meadow. While cows and wildlife made a path to the water, people on Pearl Street made a path to the main road, Park Row.

Early New York was a revolving door of sailors, and the South Street Seaport was the economic engine that drove Wall Street. Pearl Street was a vital connection between the two.

By the 1830s Pearl Street had transformed into a wholesale market stretching from Coenties Slip to Chatham Street. Following the devastating Fire of 1835, the area near Wall Street shifted focus to finance; politicians and journalists often mentioned Wall and Pearl Streets in the same breath.

Pearl Street also bordered the landfill blocks of the South Street Seaport: Water, Front and South Streets. Transactions surrounding the goods and commodities in the store-and-loft buildings of the Seaport flowed south on Pearl Street. A good many sailors, history would suggest, went in the other direction.

Visiting sailors arriving at the South Street Seaport, once on foot, invariably found themselves on Pearl Street. If they turned right and headed north, a path worn over thousands of years naturally led (ironically both directly and through a series of westward-turning blocks) to the most densely packed blocks of brothels in the Five Points.

Pearl Street extended above and below the South Street Seaport as a vital link to different the worlds of business in Wall Street and the Five Points. The lost connection of upper Pearl Street explains a lot when it comes to the notorious history of the Five Points.

The Ratzer Map of Colonial New York shows the undeniable artierial-like connection Pearl Street made between the South Street Seaport, Wall Street and the Five Points.

Bernard Ratzer Plan of New York, 1766-67.

Upper Pearl Street’s history has been lost since the building of the Brooklyn Bridge. History, and Pearl Street, conformed to the early geography, and through geography we can bring history back to life.