Six Principles for Building Manhattan

1. Patterns of growth accelerated after Consolidation

The patterns of growth and development that had been progressing since the opening of the Erie Canal gained significant momentum after the Consolidation of Greater New York. Major infrastructure projects, such as bridges and expanded transit systems, replaced older methods like horse-drawn carriages and ferries, reshaping Manhattan’s trajectory into a hub for industrial and factory-driven activities. Steel-frame loft buildings soon proliferated across the island, especially up and down Broadway and Fifth Avenue.

2. Architectural use and technology, not style

In understanding Manhattan’s built environment, the function of a building—whether it was a residence, shop, or warehouse—and the technology used in its construction—such as brick, cast iron, or steel framing—is far more significant than its architectural style. Though styles like Greek Revival, Gothic, or Renaissance can offer insight into a building’s historical context, relying solely on stylistic classification can be misleading, as any structure can be designed to mimic a particular style, regardless of its actual era or purpose. Prioritizing utility and innovation in construction provides a clearer framework for making sense of Manhattan’s architectural evolution.

A Greek Revival building located on 34th Street near Park Avenue South was described in a prominent guidebook as “1840s?” Knowing the area was still farmland in the 1840s, while not entirely improbable for New York, further investigation revealed that the structure was actually built in 1912 as a bank designed in a retro style.

While there aren’t many architectural anachronisms in the streetscape, the fact they exist makes it at least problematic to use styles as anything more than informal guides.

No one is likely to mistake the Beaux Art treatment of the Dutch form and stepped-gables of 13 and 15 So. William Street (CPH Gilbert, 1903/09) as survivors from New Amsterdam (left). The architect put the year on one of the building (as the Dutch actually did, too) perhaps to be sure of no confusion.

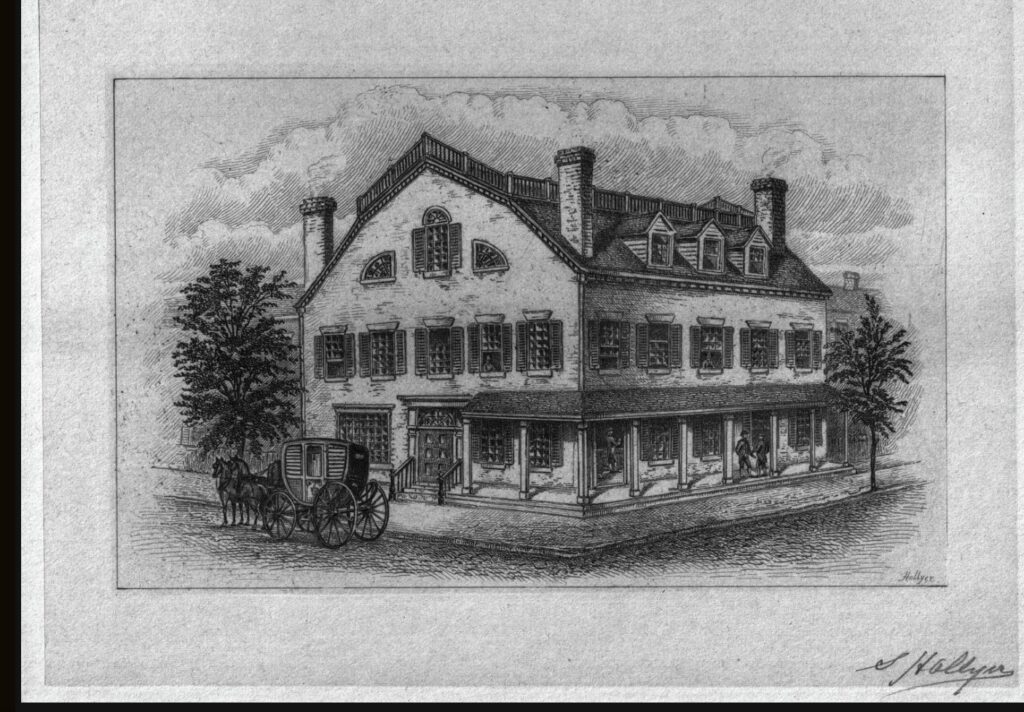

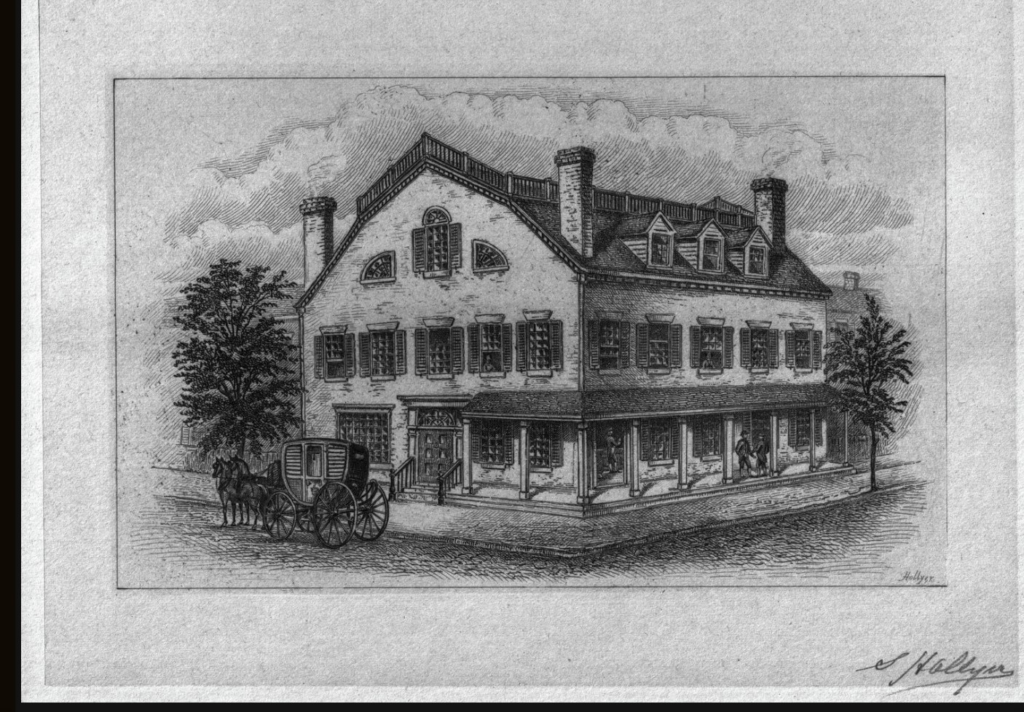

Fraunces Tavern at 54 Pearl Street is an extraordinary architectural recreation, built in 1908 in the 18th century Georgian style (below).

The fenestration and 2nd floor window lintels are consistent across all three images of what look like completely different buildings. The original Stephen Delancey home (1719), alterations (1890), and its eventual makeover as an architectural homage.

Below you can compare splayed lintels of the 2nd floor across the pictures

*The image below shows the 2nd & 3rd floors

Fraunces Tavern was the site of George Washington’s farewell dinner with his officers at the end of the Revolutionary War. It was a turning point in Western Civilization; when absolute power was his to take, Washington stepped down to abide a process, returned home, and was later elected first president. So sublime a moment in world history to that point, it warranted the Sons of the Revolution to recreate the building in the early Georgian style.

But even with anachronisms in the streetscape, using architectural styles to make sense of a deeper history leads to near meaningless relationships and correlations. Trends permeated the zeitgeist in homes, shops, hotels, banks and warehouses. Tribeca has 450 historic buildings ranging from 25′-wide loft buildings to full-block warehouses, built over six decades, and showcase at least seven styles: Italianate, French Second Empire (and the obligatory mix of the two), Neogrec, Queen Ann, Romanesque Revival, Renaissance Revival and Neo-Renaissance.

Architectural styles bring a geo-spatial chronology and order to a neighborhood, and how different styles grew out of and evolved from one to another is a rich and fascinating subject. But how the styles of Tribeca relate to corresponding development in other parts of town is not a fruitful path of deep discovery (or it is too many paths of very deep discoveries). Any correlation between architectural style and how the city developed exists only because there’s an even greater correlation between architectural technology and class-based location-market use. Occam’s razor suggests we look at the aspect of architecture most directly tied to profit margins, building use and size, not style; if all of Manhattan were built in a single architectural style, there’s no reason to think the height profiles of the city’s buildings, blocks and neighborhoods would be any different than they are now.

3. Bigger buildings replaced smaller ones

The MO was simple and straight forward on its face and at its core: New York City real estate developers practiced the art of making money from densities: bigger, taller buildings replacing shorter, narrower ones on continually re-purposed land.

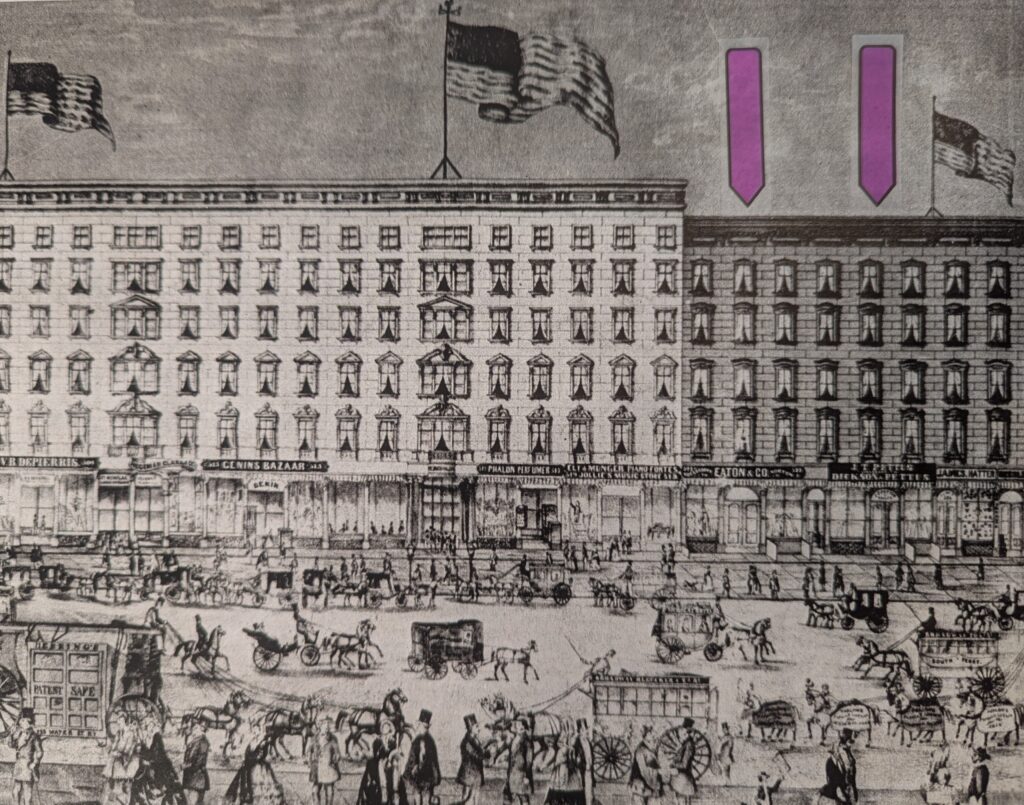

I’m aware of just a few exceptions. The St. Nicholas Hotel (1854) was the finest hotel in the city when it opened on Broadway between Spring and Prince. It was bigger than its predecessor “monster hotel,” the Metropolitan (1852), one block uptown and across the street, of which nothing remains. It was the first hotel to surpass Astor House (1836) in refinements and luxury services. It opened a second section within a year to take up the entire Broadway block with 1,000 rooms. Two sections from the addition continue in the street wall on Broadway today .

The other exception is the oft-cited example that “proved the rule.” Considering his stature, to deliberately not develop New York’s most expensive piece of real estate, JP Morgan was making a seismic statement. His many neighbors overlooking his headquarters were quite the benefactors.

Drexel, Morgan & Co. (Gilman, 1873). Library of Congress.

23 Wall Street (Trow & Livingston, 1914)

One can almost decode the history of a block simply arranging buildings by height, shortest to tallest, and you’ve got their chronological order as well.

4. City Hall was an epicenter of growth

See post: City Hall: Epicenter

5. Development followed transit

The city was pushed uptown by immigration, pulled uptown by high society, and pumped uptown by the daily act of commuting to work.

see post: Manhattan’s two-part skyline

6. Every building-type moved uptown

Everything eventually moved uptown…from homes, shops, and factories, to tenements, banks and warehouses.

See post: City Hall: Epicenter