Every New Yorker knows “the city” moved uptown; but what, exactly, does that mean beyond the fact that more buildings were built?

The problem with defining a city isn’t that there aren’t any good definitions for what makes a city, a city, there are a lot. Can any explain what moved uptown on Manhattan Island?

Let’s look at a few definitions and see how they inform our idea of a “city.”

Population is one measure of a city. As population increases, society transforms from a village to town to city; but we’re looking for a description that informs the built environment.

It’s worth noting that in Europe a cathedral defines a city. Of course, we disestablished state churches after the Revolutionary War. Houses of worship are immensely helpful for understanding how different communities moved through the city, but of course, this isn’t the “city” we’re looking for.

A commissioner of the grid plan stated, “cities were composed principally of the habitations of men.” That may have been sufficient from a time when the built environment was in a crude state of differentiation and less than 10% of the population lived and worked in separate buildings, which looked strikingly similar functioning as homes, workshops, and stores. The “habitations of men” moved uptown, and underwent a process of differentiation the commissioners could have only imagined.

The legal definition, a “municipal corporation,” describes the borders, politics and administration of the city. As a municipal corporation, New York largely had a laissez-faire attitude toward growth and development; but three times: Consolidation in 1898, and 1916 and 1961 zoning laws, transformed and shaped the city in different ways.

Consolidation saw the expansion of the city from just Manhattan Island to include the outer boroughs. Within a decade, the Manhattan and Queensboro Bridges (1901-1909) were constructed, joining the Brooklyn Bridge (1883) and Williamsburg Bridge (1896-1903) to connect Manhattan with the outer boroughs. In the 1910s, trucks and bridges replaced horses and ferries to move goods on and off Manhattan, and patterns of growth underway since the opening of the Erie Canal accelerated, and the city became a factory island. Steel-frame loft buildings proliferated all over Manhattan, along every part of Broadway, and especially around Madison Square.

Then too, zoning laws in 1916 (the “wedding cake” design), and 1961 (with Privately Owned Public Spaces), shaped the skyline, and the city’s public sphere in different ways.

But neither zoning laws nor Consolidation say anything about what moved uptown.

Lewis Mumford, author of The City in History, among his many descriptions of cities, said cities were “the most precious collective invention of civilization […] second only to language itself in the transmission of culture.”

Culture is an interesting word, some sort of culture did, it seems, move uptown.

It’s worth considering too that Mumford said,

No single definition will apply to all its manifestations and no single description will cover all of its transformations, from the embryonic social nucleus to the complex forms of its maturity and the corporeal disintegration of its old age.

But we’re looking for a very specific manifestation and transformation; we’re looking for a “city” in motion.

There are complex, intricate definitions by urban planners and social scientists meant to describe all cities, beyond what we need.

Some interesting personal favorites are:

[A] true city is where things are most dense, messy, uncontrolled and cosmopolitan.

Robert Bevan, Architectural critic

[defining a city is] a sterile typological exercise.

Michael E. Smith, Wide Urban World

In the Introduction of The City & the Theatre, Mary Henderson says, “[T]he city as the prime creator and repository of culture has not been examined with the same care or enthusiasm that has characterized the exploration of the ills and problems of city life.” She cites Eric Lampard, remarking that “the city has been studied for its impact on society rather than viewed as a unique and dynamic product of society.”

Henderson might regard “the city” as the metaphorical stage upon which cultural institutions of the day—theaters, shops, restaurants, museums, hotels and other venues for cultural interactions, are the prime creators of “city” life.

In his 1937 answer to What Is a City?, in the Architectural Record, Mumford said,

The city in its complete sense, then, is a geographic plexus, an economic organization, an institutional process, a theater of social action, an aesthetic symbol of collective unity.

…a theater for social action. With the addition of “commercial theater for social action,” we have the heuristic lifeline needed to access the inner workings of how Manhattan, physically, historically, and architecturally makes sense.

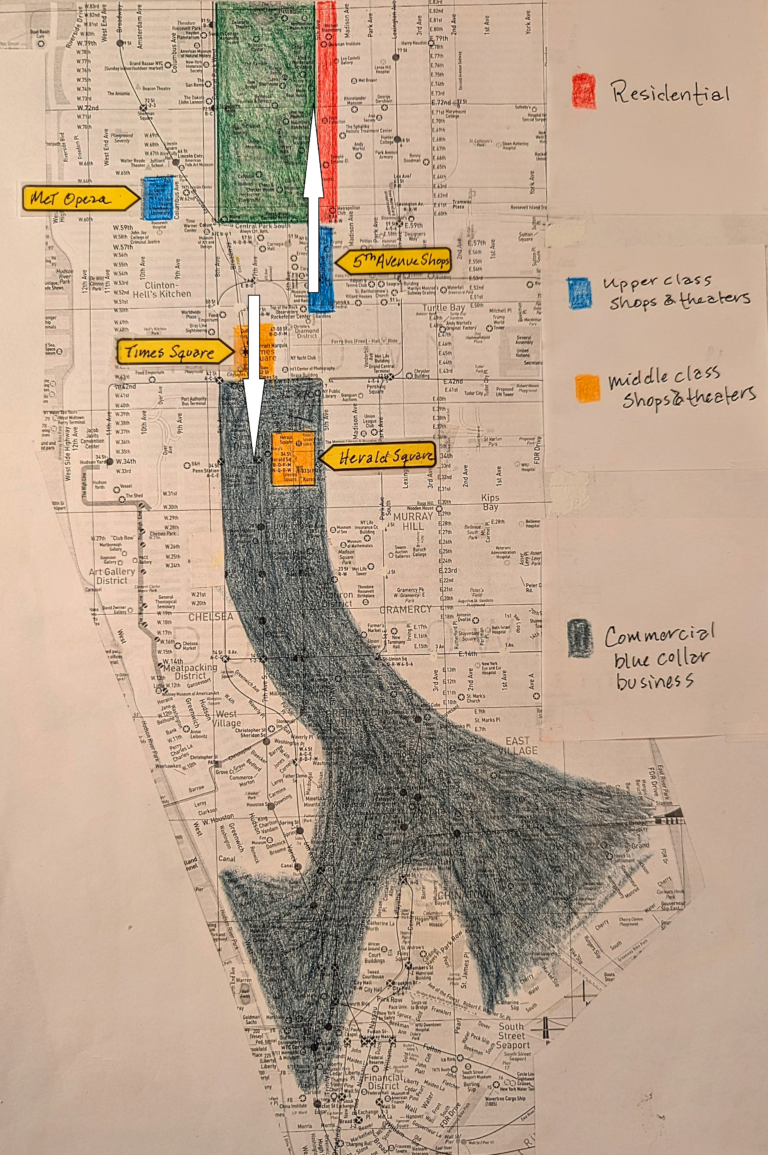

Structures housing a shape-shifting arrangement and set of evolving commercial institutions for cultural activities, both as individual establishments and in neighborhood-based location-markets, did not move uptown in any coordinated or synchronized way, but in identifiable assemblages comprised an uptown shifting “center,” led by a vanguard of the most fashionable elements, across geography and the grid, uptown through the middle of Manhattan.

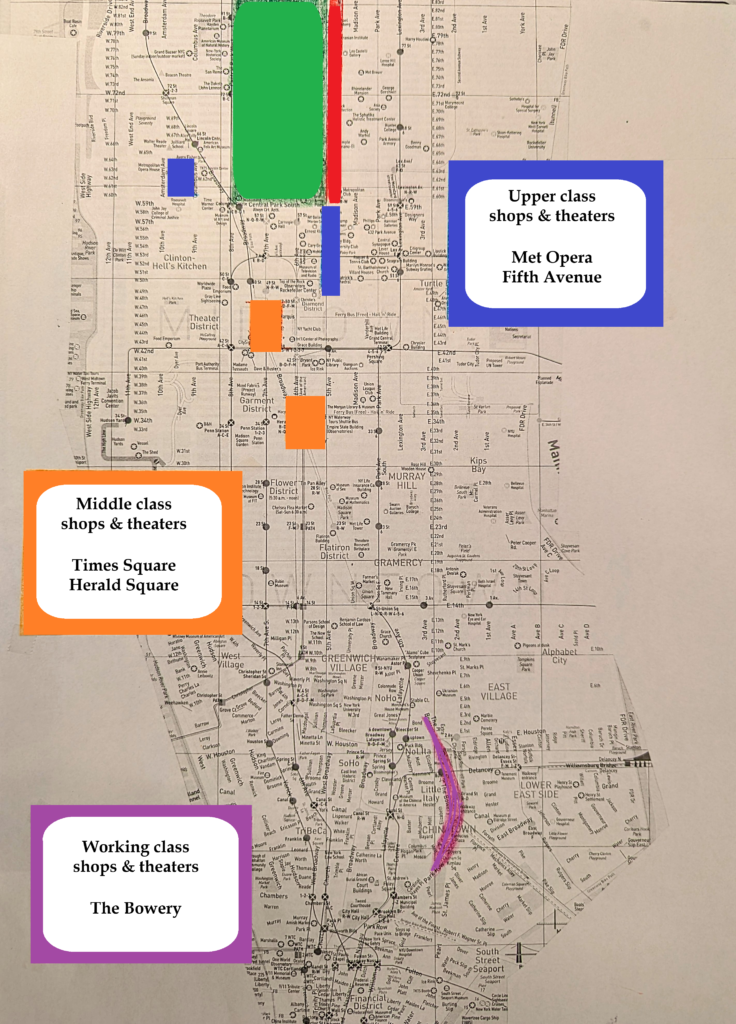

An elite, commercial “theater of social action” in the form of retail shops and theaters led the way and precipitated a middle class version around it, and then moved uptown again.

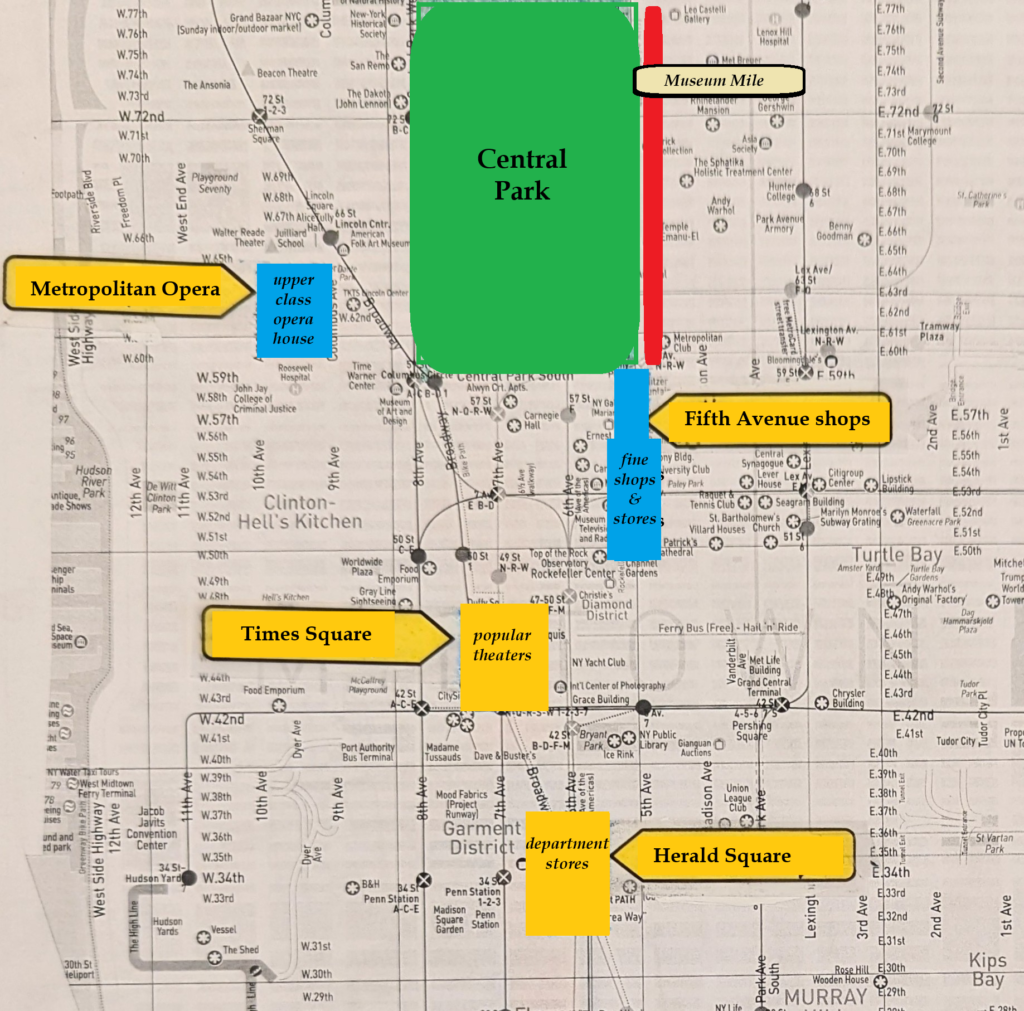

The “city” that moved uptown on the Island of Manhattan is a composite of today’s Lincoln Center, Fifth Avenue’s retail shops, Times Square, and Herald Square.

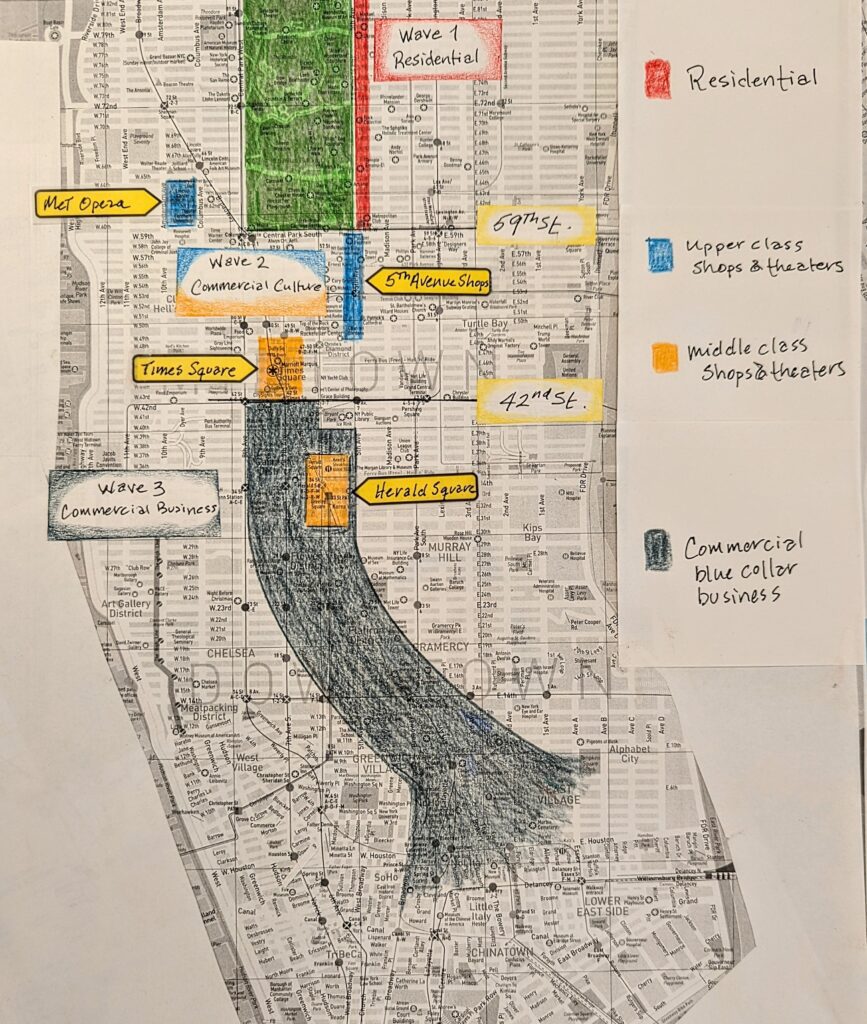

Together, these Manhattan neighborhoods were part of a single wave of development, distinct from two other uptown-moving waves: an earlier residential, and later wave of commercial business.

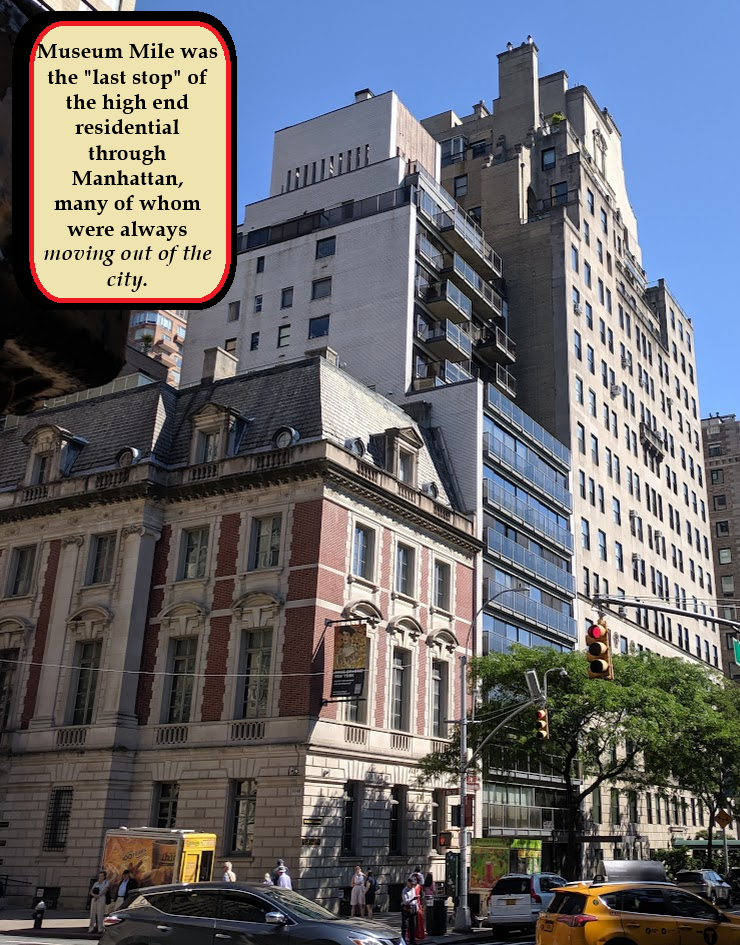

Museum Mile, Fifth Avenue above 59th Street, was the “last stop” of the high end residential district’s move uptown. The Astor family was living around City Hall in the 1830s, and across from Central Park in the 1890s, with stops in SoHo and Madison Square (for the Gilded Age) in between; Sixty years, four locations, three generations.

The majority of Fifth Avenue blocks facing Central Park are comprised of buildings from one of three periods of development, all residential: Beaux Arts mansions, pre-War, and Modern apartments. With a few museums, little to no commercial activity is the hallmark of development above 59th Street. Most importantly, of course, the wealthy were always moving out of the city.

From left to right: 1009 Fifth Ave, The Duke-Semans mansion (1899, William Thomas Hall for Benjamin and Sarah Duke); 1001 Fifth Ave (1978, Philip Johnson), 998 Fifth Avenue (1912, McKim, Mead & White).

A first wave of homes, churches, clubs, schools and early residential hotels, something that looked like a suburban residential neighborhood, was followed by shops, theaters, and a “city” of commercial social action.

These centers for commercial culture, in turn, were overrun by larger buildings for manufacturing, industry, wholesale trade, and offices. There was for a time a blending of retail, wholesale and manufacturing, along with blue collar and white collar operations in steel frame loft buildings around Madison Square…the subject for future posts. The trend, nonetheless, would be to the office tower, not the factory building.

Each wave was larger than the one before… homes got bigger, stores got larger, and places of “work” got significantly taller.

Below is a conceptual scheme of the history; the Midtown Business District will be addressed separately.

New York’s earliest city of fine shops and theaters was around City Hall, where it grew in class and status through the 1850s. In the mid-1850s, an attenuated city stretched from Canal Street (where Arnold Constable had been since 1826) to Union Square, where the Academy of Music opened in 1854. In between, the finest hotels, shops, and more theaters went up and down Broadway and east on Grand Street, the heart of today’s SoHo (the shorter cast iron buildings).

In 1869, after the Civil War, shops and theaters began to encroach on the residential neighborhood of Madison Square, which, with its apartment-hotels and enormous clubs that looked like overblown brownstones on wide avenues and streets, never had a normal neighborhood feel.

The next post will look at how the city came from Madison Square; here is how the city came to be where it is today.

The Garment District would engulf Herald Square, the middle class shopping district, and developed up to 42nd Street and the boundary of Times Square, the middle class theater district.

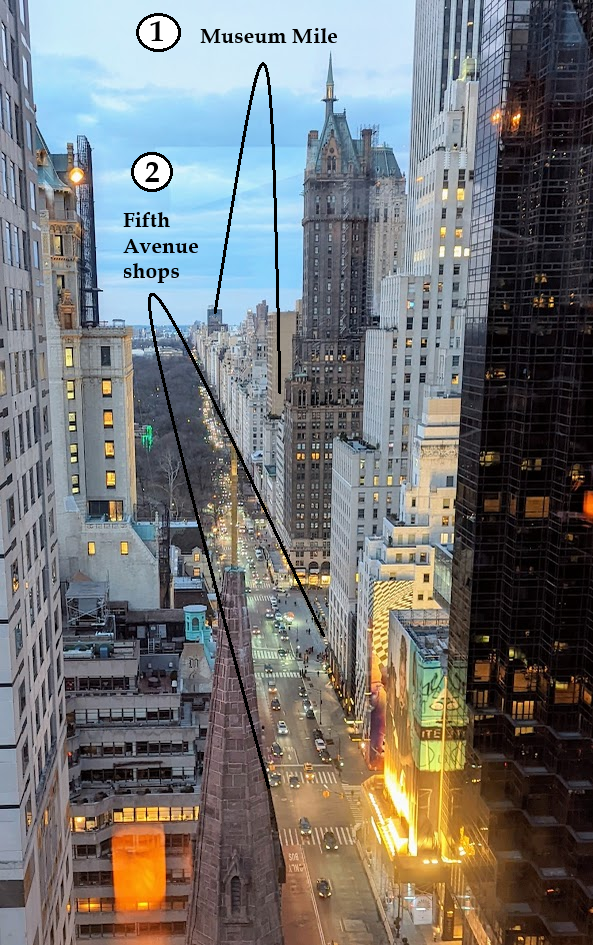

Like fault lines in the built environment, cornice heights above and below 59th and 42nd Streets show how the waves of built environment meet on Fifth and Seventh Avenues respectively.

Today’s New York city is largely in a box on the grid, bounded downtown by either 34th or 42nd Streets (depending if you include Herald Square, the city component swallowed by the Garment District), and uptown by 59th Street, with the addition of Lincoln Center, ensconced a few blocks into the “suburbs” of the Upper West Side.

Looking down 7th Avenue from 48th Street; Times Square into the Garment District

Looking up Fifth Avenue from 55th Street; the retail shopping district into Museum Mile

Arrows show the POVs for the images above. Notice the well-lighted blocks are in the “city” blocks of commercial culture, and look into the downtown blocks of the Garment District, and the uptown blocks of (non-commercial) Museum Mile, the last stop of the high end residential district’s move uptown, who it should be noted, were always moving out of the city.

Included with shops and theaters were other industries of commercial culture.

A working class theater and shopping district once existed on the Bowery. As a district, it grew, but didn’t relocate in the way other districts did. The working class Bowery entertainment was nearby the tenement district of the Lower East Side.

One theme permeated the ongoing construction and multi-modal expansion of living, working and playing that ran up Broadway and Fifth Avenue: continual class disposition. Not necessarily surprising, about as interesting as discovering ice. The wealthy not only moved away from the poor, they moved away from the middle class after middle class shops and theaters, and early apartment buildings, grew around them in Madison Square.

It’s often said the Patrician class were moving away from the “industrial evils” of the garment trade, but more proximate in time and space to the departure of families like the Astors, Schermerhorns and Roosevelts from Madison Square to Central Park, were the proto-apartment forms sprouting all around them. Apartment-hotels and clubs, which served as long and short term living arrangements, had already been around; from the 1870s – 1890s came French flats, bachelor flats, family apartments, artists lofts, and early coops, in addition to more apartment-hotels and clubs; none referred to in their time as apartment buildings.

As Times Square represents (and actually is) the middle class theater district, and Herald Square represents (and actually is) the middle class retail district, Madison Square represents (and historically was) the evolving middle class residential situation that led to the apartment building.

The department store was “worked out” between City Hall and Madison Square, where it reached its social height. The office tower was “worked out” in the Financial District, and transplanted to Madison Square in 1893 with Met Life, then the apartment building was “worked out” all around Madison Square itself.

All three came together in Madison Square when telephones and electricity were new, and they were the first to have both during the Gilded Age.

The modalities of life were re-configured through New York’s three-dimensional matrix of steel, stone, and glass with elevators, pneumatic tubes, dumbwaiters, telephones, and electricity.

The upper class were slowest to accept newly configured lifestyles; single family homes made it all the way to Central Park. An acceptable apartment building for the upper class came to Fifth Avenue in the 1910s.

The built environment is a shmear of class-based commercial cultures. A wide diversity of architectural forms and styles can be found uptown, where the upper and middle classes passed through, and a relative dearth of architectural variety and forms downtown in working class neighborhoods around the Bowery, where the basic housing form is the tenement, though they could be quite striking and beautiful in basic dimensions. In the uptown “interim districts” of SoHo and Madison Square, the blockfronts of New York are generally characterized by a profusion of the most beautiful buildings ever built for what we would consider today the most mundane, commercial, wholesale and industrial purposes.

The Bowery was a mirror to the changing times on Broadway, where it runs through today’s SoHo.

A quick look at its history… in the 1850s when that part of Broadway had the finest shops, hotels and theaters, the Bowery was a working class, but largely respectable, entertainment district with beer gardens, theaters, museums and variety shows. In the late 19th century, the Bowery’s elevated train ran above a crime-ridden area, while Broadway turned into a commercial hub for wholesalers. Through the Great depression, while Broadway declined to become part of the defunct district known as Hell’s hundred acres in the 1950s, the Bowery sank to become Skid Row.

Select bibliography

Burrows, Edwin G. & Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, Oxford University Press, 1999.

Henderson, Mary, The City & the Theratre, James T. white, 1973.

Lockwood, Charles, Manhattan Moves Uptown, Houghton Mifflin, 1976.

Stern, Mellins, and Fishman, New York 1880: Architecture and Urbanism in the Gilded Age, Montacelli Press, 1999.

Stern, Gilmartin, Mellins, New York 1930: Architecture and Urbanisn between the World Wars, Rozzoli, 1987.

White, Norval, New York: A Physical History, Atheneum, 1987.

Internet Resources

Daytonian in Manhattan, Tom Miller

The New York Historical (formerly The New York Historical Society)