Part II of the How Business Overran the “City” explains why there’s a miles-long gap between the skyscrapers of Lower Manhattan and the Midtown Business District.

Through decades of near non-stop economic and population growth, New York’s two-part skyline is the product of timing, technology and transit. Otherwise, the natural laws of real estate, to seek a property’s “highest and best use” in the determination of what was “legally permissible, physically possible, financially feasible, and maximally productive.”

General Research Division, The New York Public Library. “The Elevated Express” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed February 5, 2025. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/465dc0f0-5d6f-013d-bf87-0242ac110004

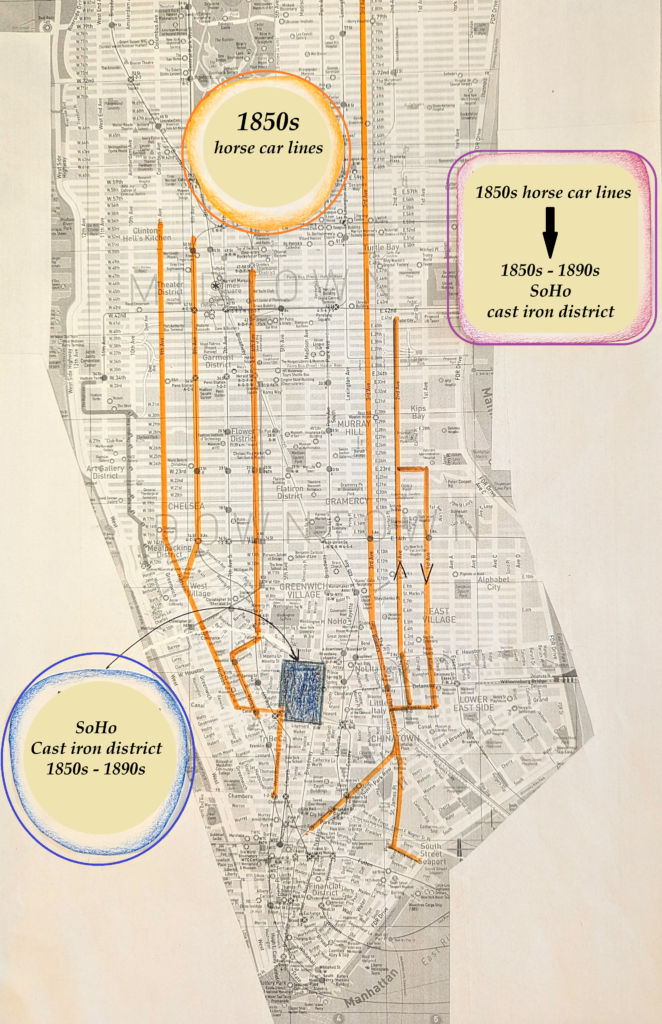

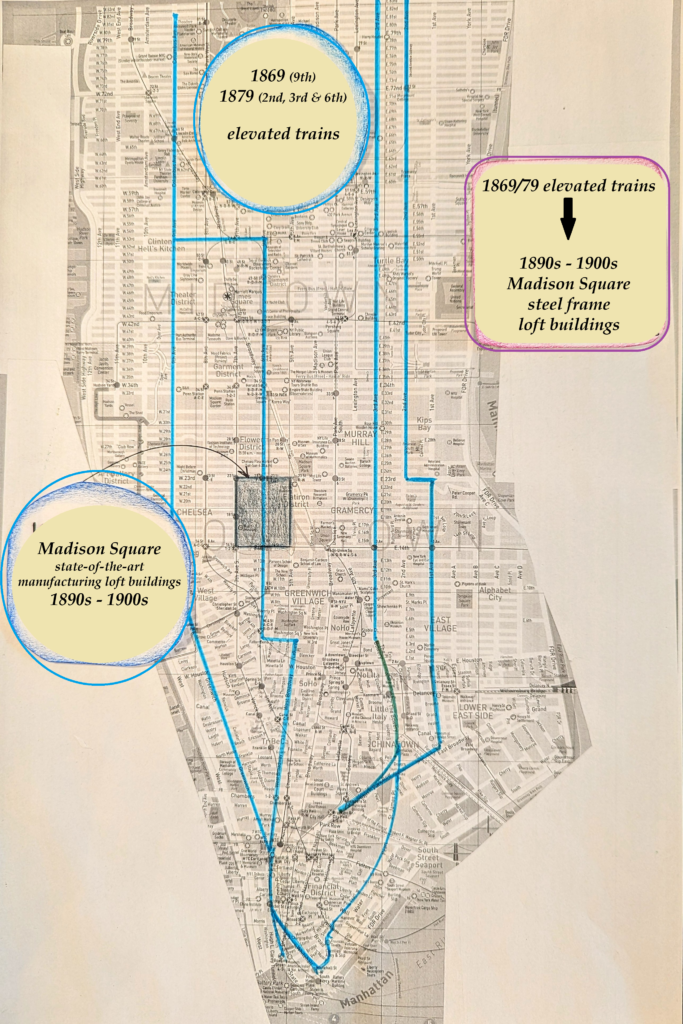

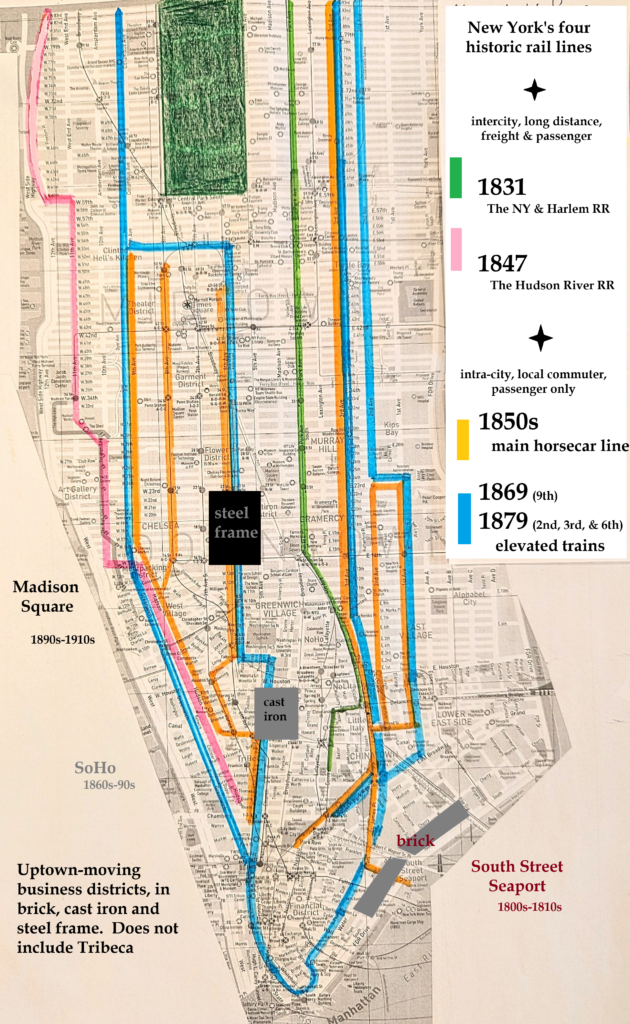

What made possible, and sustained all uptown growth, was a feedback loop between local rail transit: horsecar lines, elevated trains, and early subways, and ever-larger, uptown-moving business districts. There is virtually no trace of the first two rail systems that came and went on Manhattan.

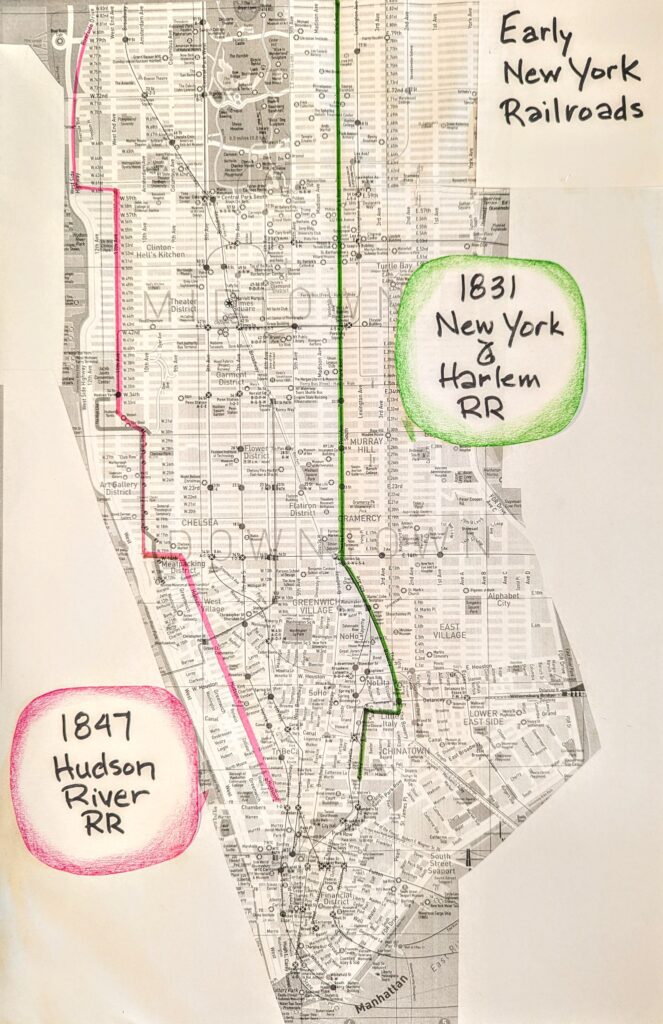

The first rail lines extended long distances “through the core and on the shore.” Their variously direct and indirect descendants are: MetroNorth’s Harlem Line, and The Highline elevated park, both over the ruts and rails of the original New York & Harlem (1831) and Hudson River (1847) Railroads. Both lines carried passengers and freight.

Later systems of horsecars, elevated trains and then subways, between the two earlier “core and shore” lines, were for local commuting. The Highline was part of a later freight system from the 1930s, built along the route of the earlier line.

The long, skinny shape of Manhattan, and the fact the city started downtown, would have extraordinary ramifications for the city’s development.

The city by any definition had nowhere to go but up. New York’s horsecars, elevated trains, and the first subways lines were virtual straightaways running up and down the island. New transit came generationally, and successive systems worked together to the same end: building business districts at one end, and farther-flung suburbs at the other.

Successive transit systems ran at grade, above, and then below ground. Channels of transit didn’t substitute, but supplemented one another, towards the end of ever denser business districts.

By the daily act of going to work (technically these New Yorkers were not “commuters” who, by definition, hold discounted weekly or monthly passes), residents of neighborhoods like Hells Kitchen, San Juan Hill and Yorkville, provided the occupational workforce for the third wave of blue collar commercial business districts that pushed uptown through Manhattan.

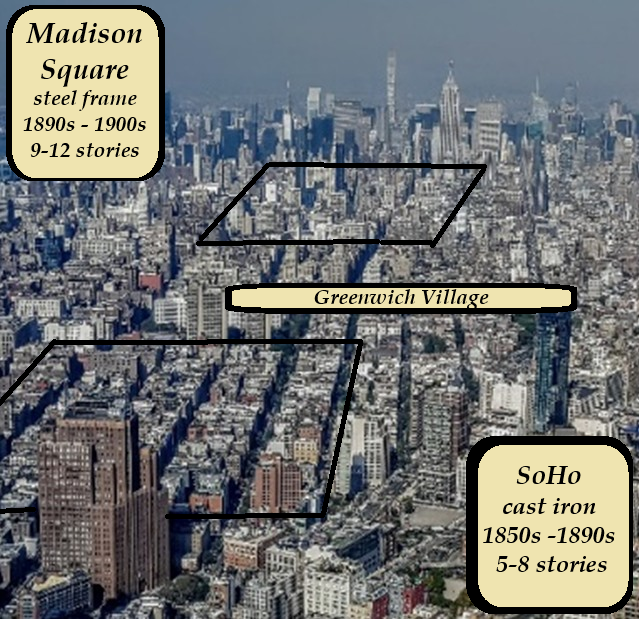

Transit was geo-spatially indexed in time and space to development through the center corridor such that cast iron buildings in SoHo from the 1860s and 70s were predicated on the horse car lines of the 1850s. Likewise, steel-frame manufacturing loft buildings around Madison Square from the 1890s and 1900s were predicated on the elevated trains of the 1880s.

As much as any force pushed or pulled the “city” uptown, the city was pumped uptown generationally by the daily act of going to work in ever larger, later, farther uptown business districts.

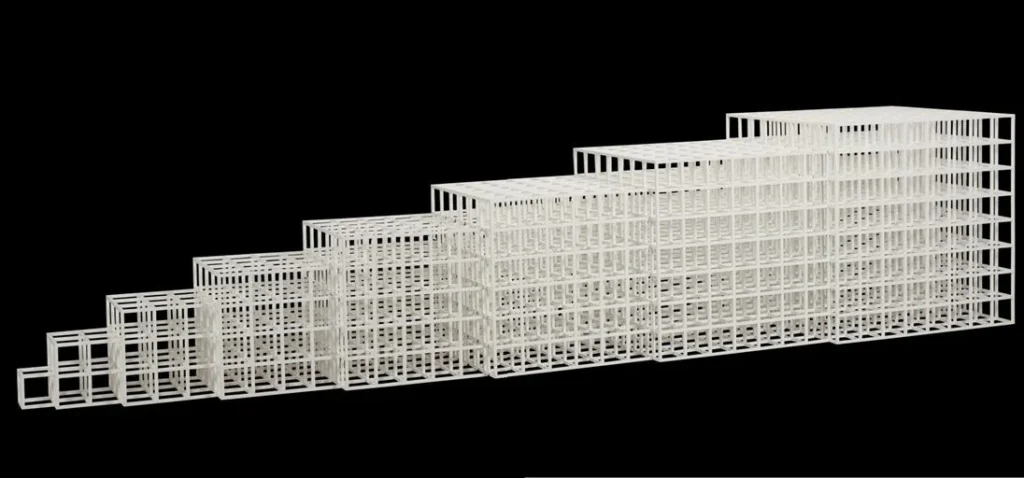

Open Geometric Structure IV, 1990. Sol LeWitt. credit to https://MutualArt.com

The skyline slopes up from City Hall to Central Park. Sol LeWitt may have been trying to represent the New York skyline with his minimalist work. Horizontal steel rails and ever-larger vertical cast iron and steel cage construction engaged in a feedback loop to build New York City like ski slope in reverse. In Coney Island they bent the steel for rollercoasters.

The view below is from The Lower East Side, looking across the tops of tenements, which were about the same height as cast iron buildings in the blocks of SoHo to the left. The skyline gradually ascends as buildings get bigger,

Business districts progressed uptown in cast iron and ever-taller versions of steel frame because it always made more sense, at every point in time, for developers to look uptown to declining residential neighborhoods of brownstone home-turned-boardinghouse communities for redevelopment, rather than downtown to neighborhoods that had already been industrialized decades earlier. Though buildings were obsolete or becoming so, such districts were still going concerns.

Redevelopment in situ did happen along high volume and value streets and avenues, like Broadway and Fifth Avenue, where a ridge goes physically up the island. Otherwise, technologies advance as business districts in cast-iron and steel frame through SoHo and Madison Square, and generally west of Broadway and Fifth Avenue.

The Great Railroad Differential

There was a great railroad differentiation between the New York Central, whose long distance line originally extended all the way to City Hall, and the local commuter rail systems that came and went on Manhattan between the 1850s and the 1940s; between the core and the periphery.

As local rail systems saturated the periphery with redundant channels of transit, over the same period, rail travel through the central corridor retreated from development. The New York & Harlem Railroad moved back from 27th Street to 42nd Street in 1872 with Grand Central Depot, facilitating growth through the center.

Select bibliography

Barr, Jason, Building the Skyline, Oxford University Press, 2016.

Burrows, Edwin G. & Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, Oxford University Press, 1999.

Kaplan, Justin, When the Astors Owned New York, Plume, 2006.

Lockwood, Charles, Manhattan Moves Uptown, Houghton Mifflin, 1976.

Stern, Mellins, and Fishman, New York 1880: Architecture and Urbanism in the Gilded Age, Montacelli Press, 1999.

Stern, Gilmartin, Mellins, New York 1930: Architecture and Urbanisn between the World Wars, Rozzoli, 1987.

White, Norval, New York: A Physical History, Athenuem, 1987.