This post builds on The Bowery & Chatham Square, heading up a few blocks to where the Manhattan Bridge intersects Canal Street. The Bull’s Head tavern dominated the immediate area as the unofficial headquarters of the cattle market from the Colonial days of the 1750s up until 1825, when society elites set their sights on transforming the area and building an upscale theatre in the cattle yard of the Bull’s Head. This post will poke around the area, recount some of the rich, dynamic history of the Bowery theatre, and see what’s left from yesteryear.

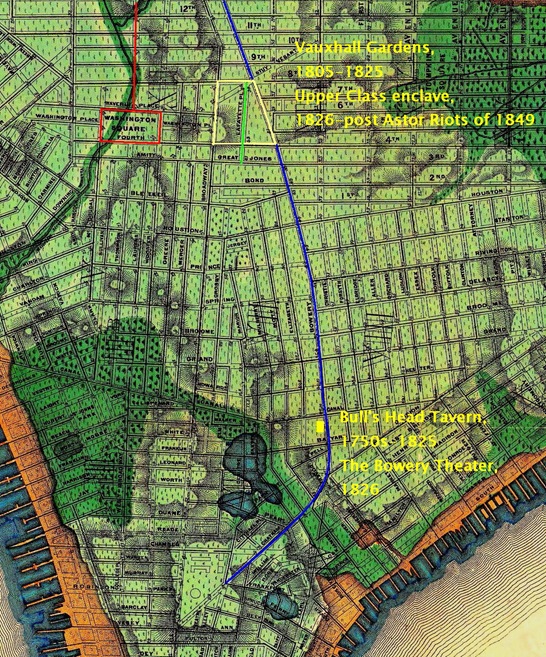

Below is the area we’re looking at. The curved yellow line (#1), was the subject of the earlier post; this post looks at area #2. Together, they make up the eastern border of “traditional” Chinatown. Just for reference, City Hall Park is outlined in green; Five Points’ exact location (and the original streets that actually made the “five points”) looks like a partial asterisk; and the straight green line shows Division Street, the boundary between the Delancey and Rutgers farms. Everything was incredibly close.

Early geography goes a long way in explaining why these areas developed the way they did. Here’s the Viele map with the same landmarks identified…

City Hall Park fits snugly on a patch of high ground; The Five Points was often a noisome area of stinking, sinking landfill built over the Collect Pond; and Chatham Square was the first solid ground one encountered leaving downtown on the Boston Post Road. You can feel the different levations of the terrains walking the area today!

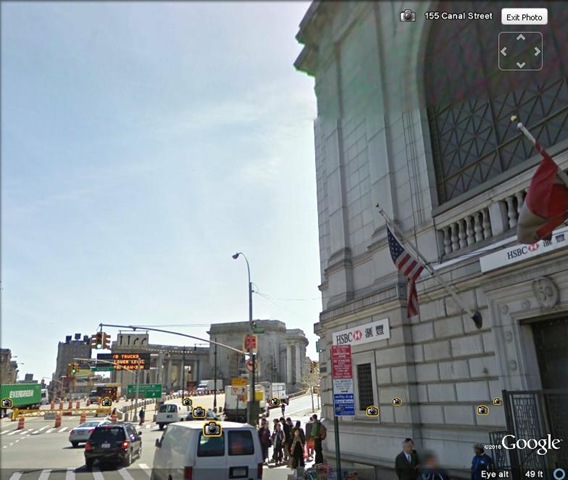

At the Bowery and Canal Street today it’s impossible to get a feeling for how this area once related to the Lower East Side. It’d always been a major north-south conduit, but the Manhattan Bridge (1909) flipped its orientation and its now where Manhattan handle’s cross-country traffic (and why it has so much commercial traffic).

At this historic corner today, the bronze-topped Republic National Bank (1924, Clarence Brazer) is in a very sorry spot to be appreciated, and many architectural guides ignore it. This is a good picture only because the photographer (the New York Daily Photo) is standing on a no-man’s land of traffic islands. (See the Woolworth Building to the left? It’s across from City Hall.)

Republic National Bank (1924, Clarence Brazer), courtesy New York Daily Photo

Likewise, the Manhattan Bridge Arch and Colonnade (1915, Carrere and Hastings) might be an impressive monumental work…somewhere else. Like the bank across the street you can’t see it until you’re on it. No long street vista provides the distance necessary to appreciate it. The orange pylons don’t help either. Confucius Plaza apartments at the right (1976, Horowitz & Chun) has a unique curve that is identifiable from many blocks around.

To see their relative positions, this looks east along Canal Street to the Manhattan Bridge entrance. The Bowery crosses between the bank and the bridge.

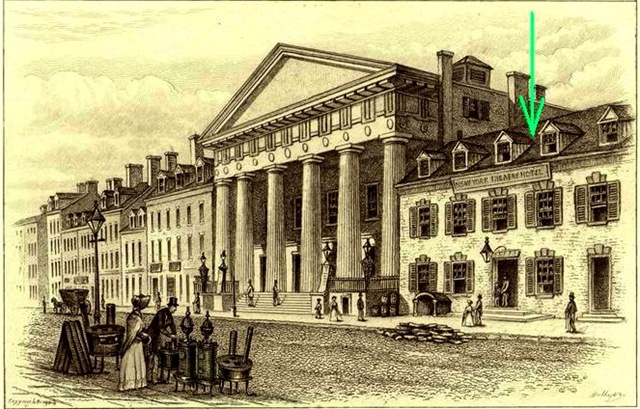

Turning the corner to the right…the Bowery Theatre stood from 1826 until 1929 where Jing Fong once stood [updated 2024] (the tan building with the red lettering).

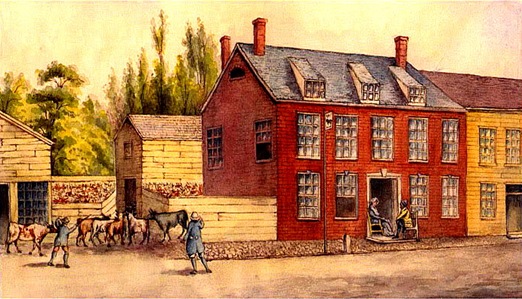

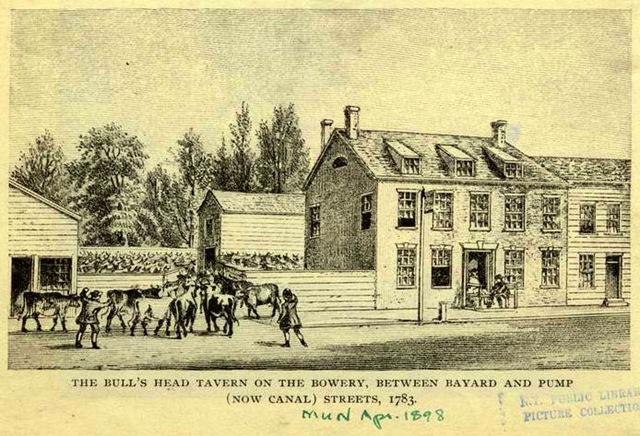

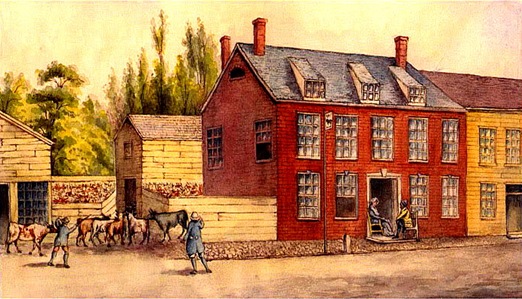

From the 1750s until 1825 the block above was the last stop where, according to Gotham, “upstate drovers like Daniel Drew were herding an estimated two hundred thousand head of cattle across King’s Bridge each year and making their way, accompanied by hordes of pigs, horses, and bleating spring lambs, down Manhattan to Henry Astor’s Bull’s Head tavern and adjacent abattoirs.”

New York was unique, for a coastal city, in having a thriving cattle market, and no other place in Manhattan resembled more the “wild west” (still decades away) than Chatham Square in the early 1800s—and the anchor was the Bull’s Head tavern. George Washington, the tavern’s most famous patron, stopped here on Evacuation Day, 1784.

The theatre would actually occupy the site of the cattleyards, to the left. The tavern itself would, according to Kenneth Dunshee’s As You Pass By, become “the New York Hotel and still later was occupied by the Atlantic Garden.”

The idea of erecting an upscale theatre at this spot was a curious one. Even with respectable residences and markets, and stores like Lord and Taylor and Brooks Brothers nearby, the immediate area around the Bull’s Head had always been working class. Since 1732 the main theatre in town had been the Park, just down the road and across from City Hall. According to Mark Caldwell’s New York Nights, “the half-dozen blocks that separated the Park and the Bowery Theatres, short in distance, crossed the city’s social and economic Maginot Line, and the upper strata of the town soon rebelled at the prospect of evenings at the Bowery.”

But the elite consortium that sought to transform the area around Chatham Square (which included Henry Astor himself, the owner of the Bull’s Head) had its mind on uptown when making their plans for the theatre. Terry Miller’s Greenwich Village and How it Got That Way explains what had been going on a half mile up the Bowery during the twenty years leading up to the purchase of the Bull’s Head:

In 1804 [John Jacob] Astor took over a large tract above Great Jones Street, which he opened as Vauxhall Gardens, an early version of Central Park but run as a business for profit. It acted as a magnet drawing the rich to the area, prompting them to construct their splendid new homes on Great Jones Street. When property values peaked in 1826 Astor closed most of Vauxhall Gardens to sell of the land for development. He ran a broad road through the center of the property, three blocks without a cross street, and named his creation Lafayette Place.

Vauxhall (the yellow trapezoid below) had a splendid situation with gentle sloping hills and views of the East River; it’s now the west side of today’s Cooper Square. Lafayette Place (the green line) opened the same year the investors purchased the Bull’s Head. For reference, Washington Square and Fifth Avenue are shown in red.

As you can see, following the Bowery (blue line), Daniel Drew’s 200,000 head of cattle stampeding along the Bowery would have been quite a disturbance for the upper crust to endure outside their front doors. The cattle market would relocate to around 26th Street, just east of the future Madison Square and well to the north of the wealthy enclave.

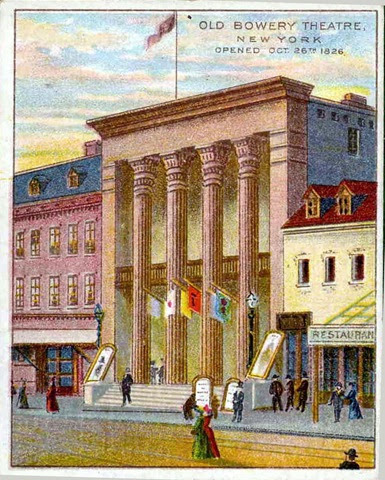

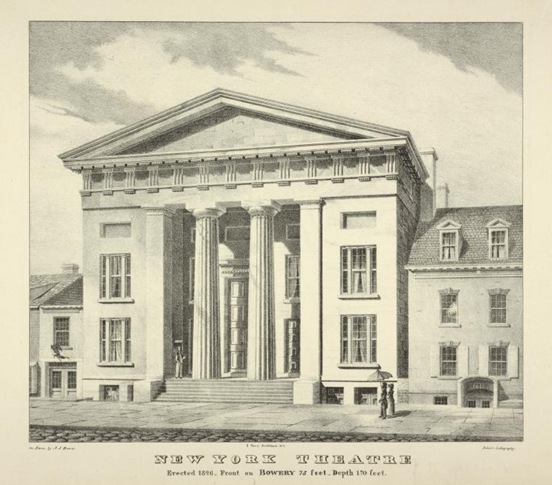

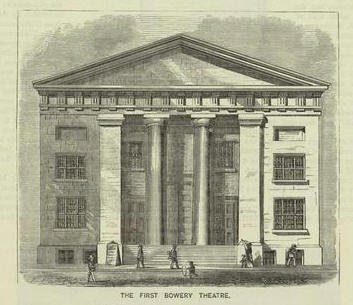

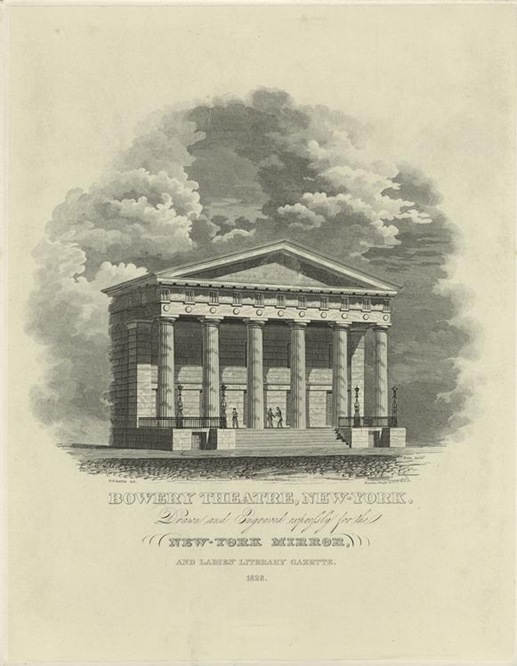

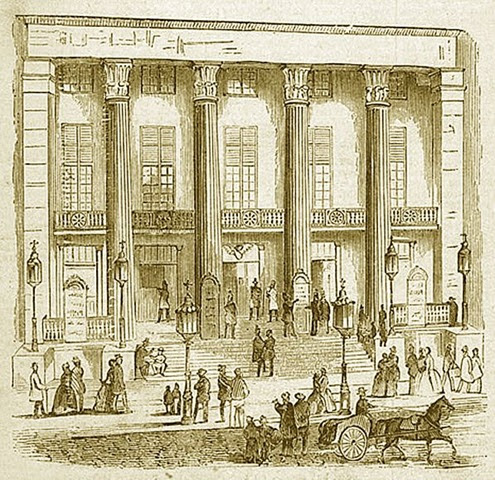

This was the picture for the Bowery Theatre I used for the post The Story Behind the Lower East Side. That was a mistake—this is not what the Bowery looked like when it opened in 1826; and it’s even a poor representation of what it looked like later on. (Sorry to even include it here, but I wanted to set the record straight.)

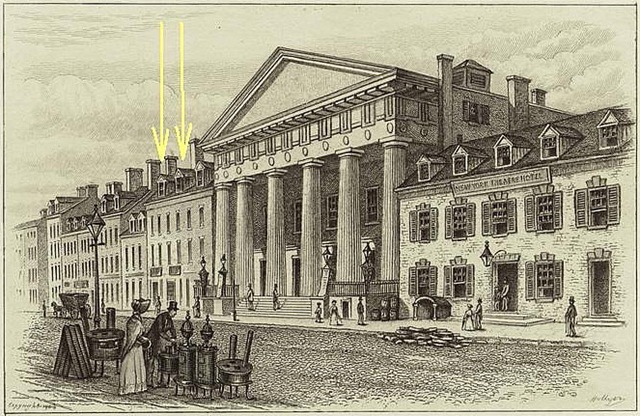

This was Ithiel Town’s 1826 building, in the Greek Revival Style he was noted for, his first New York commission. The theatre was first named the “New York Theatre,” as the title reads.

For a compelling comparison, here is Ithiel Town and Jackson Davis’ still standing Federal Hall National Monument (1833-42) on Wall Street; same architect, same period. The similarities include Doric columns, pediment, and a frieze with triglyphs and metopes. Triglyphs are the three close vertical lines; metopes are the empty square spaces between them. Together they mimic, in marble, the look of wood cross beams, the original building material of the Greeks. This is pure, simple Greek Revival—it looks like a Greek temple.

Here it is labeled “The First Bowery Theatre,” though this venue was actually never called the Bowery Theater.

In fact, over its 103 year life the theatre would have four different names and three different looks, changes that often coincided with one of the buildings many fires. The theater would burn in 1828, 1836, 1838, 1845, 1913 and (for a final time) in 1929. Two things might have contributed to the uncanny number of fires, even for a time with gas lighting when fires were common.

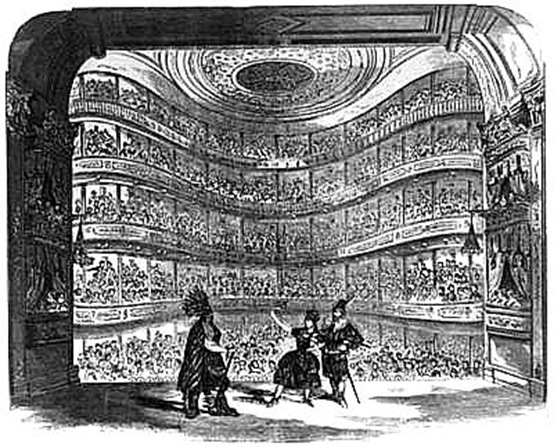

Reconstruction following the fire of 1828 brought a new look and name—now, officially, the Bowery Theatre. This explains the wildly divergent numbers reported regarding capacity—from 3,000 to 4,000; the new theatre increased capacity from 3,000 to 3,500. But increased capacity only put more pressure on management to draw crowds, especially the well-heeled for whom the theatre was built. To make sales, management added shows with mass appeal, including melodrama, horse shows and novelty acts.

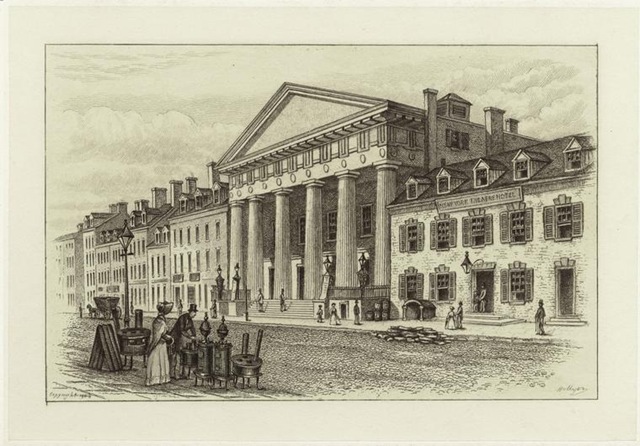

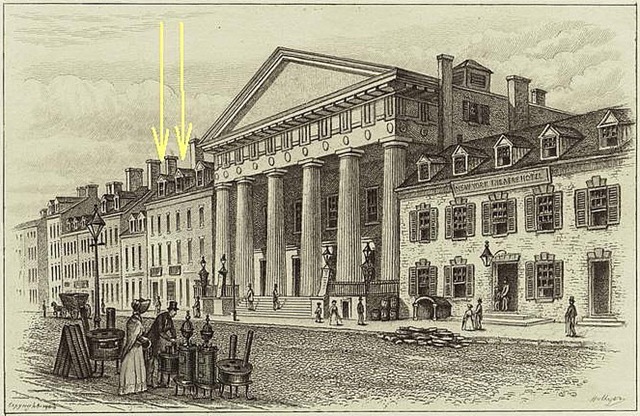

Here was the new look of the 1828, and the first Bowery Theatre. Towards the end of the post we’ll see that two of the buildings in this image are still standing!

They were were the headquarters of the Bowery Boys!

The Bull’s Head tavern was located here, and was a hotel at this time. There are a lot of similarities, and it may be the Bull’s Head tavern re-modeled, but there are discrepancies…

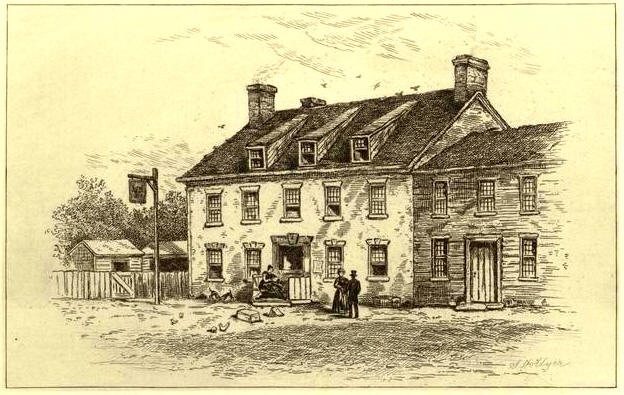

…the next two images are the old Bull’s Head from the NYPL digital collection. The gable roof, fenestration and central doorway match the hotel in the image above, but there are two more dormers and two additional entrances on the later building. Also, the chimneys match, but only in one picture, not both.

The Bowery Theatre hosted all the fads and franchises in popular entertainment, good and bad, over the next 50 years: minstrelsy, Mose the fireman, circuses, Buffalo Bill-style Westerns, “variety” shows, and Vaudeville, with nights of Shakespeare sprinkled in—even when the upper classes sought their Shakespeare elsewhere. Later, with each successive immigrant group the theatre would re-format to provide fare for its local audience…German, Yiddish, Italian, and Chinese.

The Bowery Theatre was an early venue for many theatre forms and stage acts. While on the road out west in the 1830s, Thomas “Daddy” Rice reportedly encountered an elderly stable hand and slave named Jim Crow whose dance, language, and even clothing he mimicked (or, by today’s sensibilities, more likely mocked). His act became a regular at the Bowery Theatre in 1832. “Ethiopian delineators” (white men in blackface) had been part of circus acts and stage shows since the 1820s, but with Rice’s “Jump Jim Crow,” minstrelsy would sweep the nation in the 1840s. And the minstrel show was one of the longest-lived forms of entertainment, from the 1840s until the early 1900s. To put it in perspective, around the year 2030 Rock and Roll will have been around as long as minstrelsy was popular theatre.

According to Dunshee, the 1836 fire “totally destroyed” the theatre “in less than thirty minutes.” If so, this was likely its last major facelift.

The depression of 1837 hit theaters hard. In 1842 Charles Dickens observed “there are three principal theatres in New York. Two of them, the Park and the Bowery, are large, elegant, and handsome buildings, and are, I am grieve to write, generally deserted” (The Chatham Theater was the third), James Gordon Bennett Junior’s Herald regularly attacked the theater in these years. In general, characters and acts had become so hackneyed and predictable that audience members often yelled out the next lines.Luc Sante writes in Low Life that during the 1840s “theater managers left off programming their houses as if they were still addressing the mixed and at least partly educated audiences of the 1820s and earlier, and instead began consciously catering to the immigrant mechanics [working class men] who were their actual patrons.” Basically he says, wit and repartee were replaced with elaborate sets and spectacle to appeal to the “common man,” a trend that had begun in the 1830s. Now earthquakes, volcanoes and flooding the stage for pirate “aqua-dramas” became standard fare.

In 1848 a new character would make his debut that would rock the theater world for the next decade because, simply, so much of the audience recognized itself. Mose the fireman was the typical Bowery B’hoy, and though he did not debut at the Bowery Theatre, the Bowery would host its share of performances where Mose, in his stove pipe hat and soap locks, rescued women and children and saved naive New York tourists from ne’er do wells. Mose was one of our earliest “All-American” avatars.

His likely fans, apparently getting a scolding…

Entertainment wasn’t the stratified industry it is today; up until the mid-1800s, rich or poor, bankers, merchants, pimps, and prostitutes, all went to see Shakespeare, and for a long time, in the same theatres. Theatre was the melting pot’s melting pot, and standards for decorum were nonexistent. It would be impossible today to imagine the Metropolitan Opera’s upper balconies overflowing with yelling, hissing rabble rousers bouncing lamb chop bones off the hats of white-gloved ladies, but this was early theatre, before movies, sports, and bowling night. When the Astor Opera House opened up in 1847, around the corner from Astor’s Lafayette Place, it would, with the help of its location and its program, send a warning shot across the bow of society at large: the upper class would have its own theatre.

Edwin Forrest had been a fixture at the Bowery Theatre from early on, and history remembers him best as one of the two protagonist-catalysts, along with William Macready, to ignite the Astor Place Riots of May 10-11, 1849, when both actors reprised the role of Macbeth at different theatres across town. The Bowery Theatre wasn’t one of them.

Forrest was beloved by the Bowery B’hoys and the working class for his “Americanized” interpretation of Shakespearean characters. Macready played his Shakespeare very traditional, and very “British.” Macready was playing the Astor Opera House, and the confusion as to which theatre Forrest was playing may stem from the fact that both the Bowery and the Broadway Theatres (a short-lived venue at 326 Broadway from 1847-1859) had opening nights for Macbeth on May 7, 1849. But according to the Internet Broadway Database, Edwin Forrest was at the Broadway Theatre when he fanned the flames of animosity that instigated crowds to surround the Astor Opera House and its elite attendees, ultimately leading to dozens dead and scores wounded.

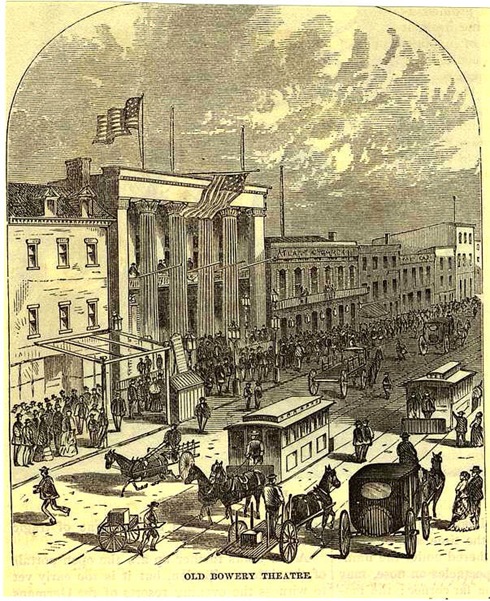

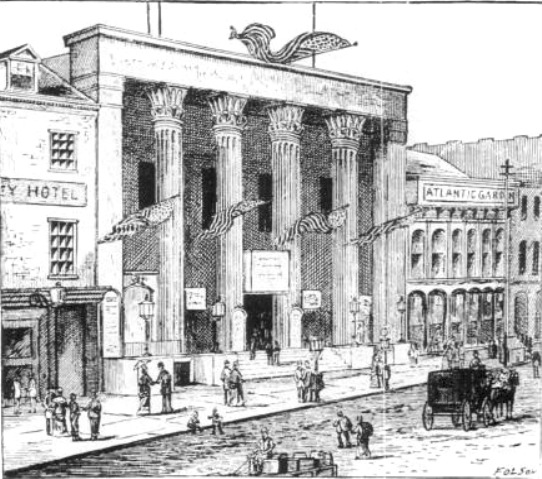

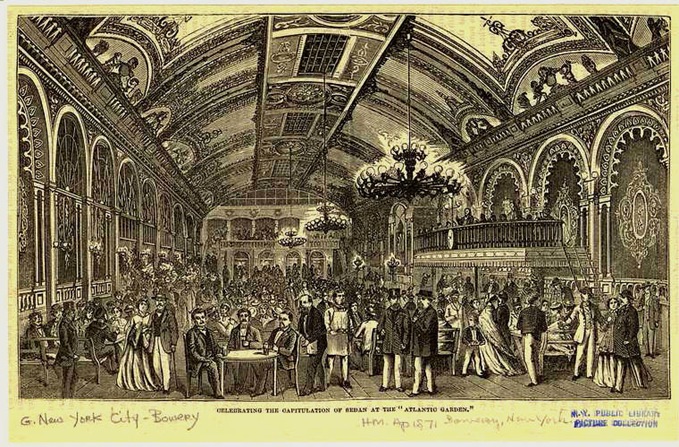

This image appeared in Harper’s Monthly in 1871. In 1853 the Second and Third Avenue Railroads were opened, merging at the Bowery and Chatham Square. The Atlantic Garden, which opened in 1858, is just north of the Bowery Theatre. The massive beer hall was a favorite of the German community that had been settling the area since 1848.

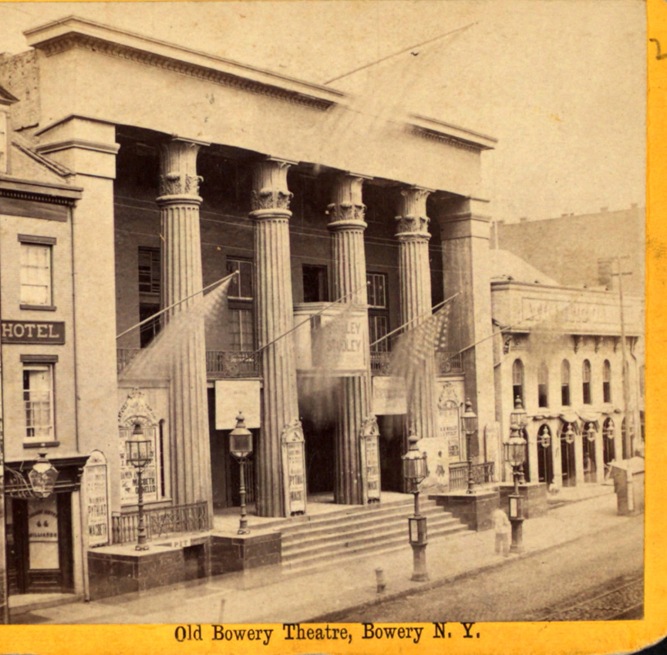

The NYPL Digital Collection doesn’t give a year for this image. The marquee between the center columns could possibly say “Studley,” and J.B. Studley played Buffalo Bill Cody to rave reviews in 1871. The placard behind the lamppost to the left reads in heavy letters, “Macbeth” and “Othello.” You can make out the sign for the “Atlantic Garden” next door. There’s also a man reading the lamppost at the curb, he must have been reading for a while since he’s not blurry.

NYPL Digital Collection, Robert N. Dennis

After the Civil War the Mose franchise had run its course and westerns, “variety,” minstrelsy, and over-the-top sets were the fashion.

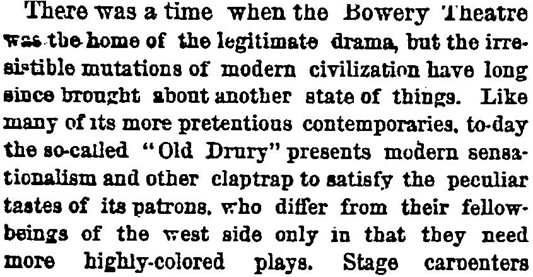

From the New York Times, September 30, 1874.

The theatre would change hands a number of times and was renamed the Thalia in 1879. According to Valentine’s Manual, “German plays and operas were the main attractions until 1888, when Amberg subleased the house to H.R. Jacobs for a year. A company of Hebrew actors gave performances in their own tongue at the Thalia during the season 1889-90. Then it was closed for a year, and during the season 1891-92 it was open for performance in German.”

A New York Times article from 1910 recounts the demographic changes to the area and how the Thalia and the Atlantic Garden, now under the same ownership, responded to the new realities.

Here’s the street in 1867, now the Thalia with the Atlantic Garden next door. Whether German, Irish, German-Irish, German-Jew, Eastern European-Jew, or in English or Yiddish, the five enormous American flags flying out front must have made whomever was in attendance feel distinctly American.

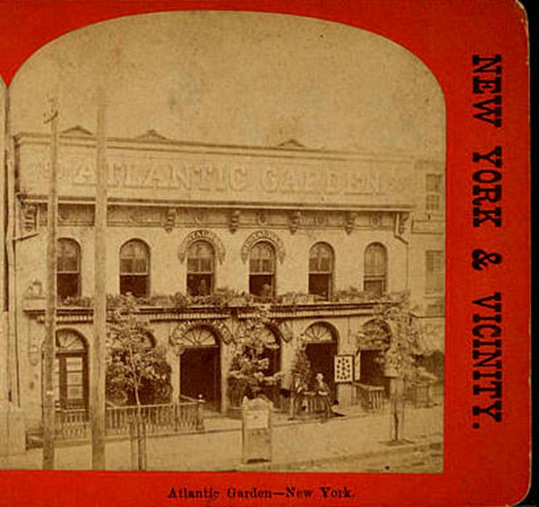

Exterior of the Atlantic Garden beer hall (1870s?)…

Interior, 1871…

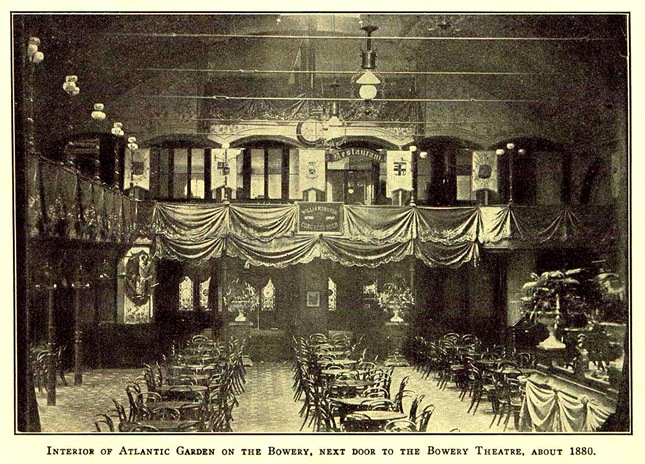

Here it is “about 1880,” from Valentine’s Manual…

A sad “then and now” picture, here is the site of the Bull’s Head tavern and the Atlantic Garden today…

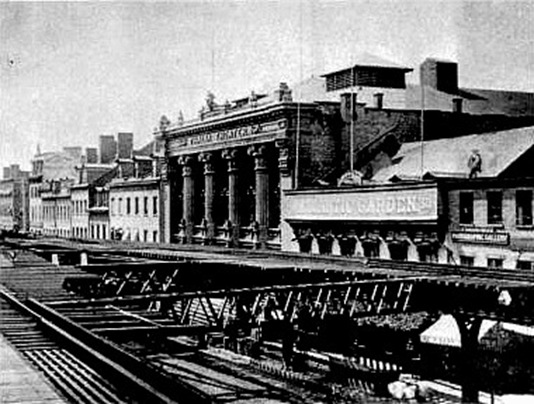

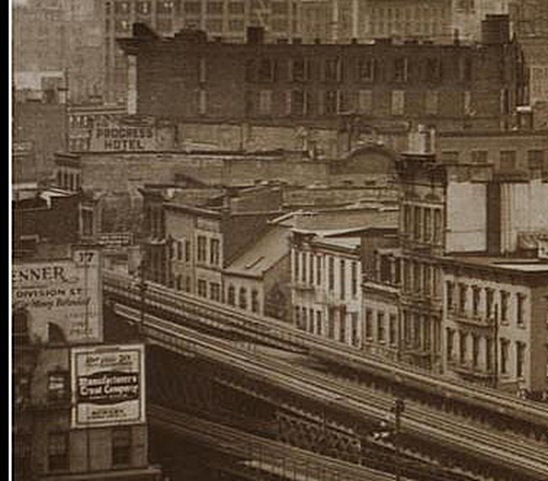

That much was sacrificed in the name of modernization (a century-and-a-half ago) is clear from the image below. From the 1880s until the 1940s, when the last one came down, elevated trains ran along 4 of the city’s 12 Avenues–for sixty years. For those who were around for the elevated trains, most people lived to see them either go up or come down, only a single generation would have had the uncanny experience of seeing the elevated trains blight out the skies in their youth, and sun return to the sidewalks and cityscape in old age. It won’t be long before the only living New Yorkers will have only known the subway.

Accordong to Lawrence Stelter in By the El, the Chatham Square hub was “the junction of the 2nd and 3rd Avenue lines, [and] until 1942 the station had eight active tracks, four platforms and two levels.” From atop the el only the upper portion of the theatre is visible. Notice there are at least eight Federal-era, dormer windows still standing! I’m not sure the year of this image, but it must be earlier than 1910 as the Atlantic Garden is not yet Yiddish.

Here is the same area in 2010. If you’d ever eaten at Jing Fong you’d have been in the space above the audience in the theater.

Photo by Lauren Klein Carton

And the two dormer-window buildings to the far left, 40-42 Bowery, were once the headquarters of the Bowery Boys. Bowery historian Eric Ferrara says a “fierce surprise raid by the Dead Rabbits on this location on July 4, 1857, sparked the infamous, bloody, two-day-long Police Riots.”

And these are the same buildings from the earlier image.

The Bowery Boy’s headquarters next to the Bowery Theatre…In 2010 a beauty salon next to dim sum.

There’s an even older building in the image still standing, the Edward Mooney house from 1789! It’s to the left with the slanted roof at the entrance to Pell Street, and Old Chinatown…

The Mooney house was from a time wealthy and poor lived nearby, and business was transacted if not in your house, near to where you lived. It makes sense that Mooney was a wholesaler in the meat market. Surely he would have done business at the Bull’s Head tavern–they were contemporary structures, overlapping some 35 years! He picked up the property at the auction of the Delancey estate after the Revolution. According to the explorechinatown.com, “it became a tavern in the 1820’s, a store and hotel in the early 20th century, then a pool parlor, a restaurant and a Chinese club, and today is a bank.” Here was his nearby neighbor…

Thank you for a wonderful discussion of the Bowery Theatre!

I am much taken by your research and labeling of the photos. My great grand uncles, the Matthews brothers, were leaders of the Bowery Boys and first Mayor of the Bowery and your shot of the BB headquarters today is a lot of fun to see.

Thank you for your site.

I enjoyed this post on the Bowery Theatre.

One point: The drawing by Folsom, from the Walling book, cannot depict 1887, since the “el” went up in 1878. I’m guessing it is drawn from the NYPL’s photo, about which there is now a note on Wikimedia Commons, at "File:Old Bowery Theatre, Bowery, N.Y, from Robert N. Dennis collection of stereoscopic views.png", which dates the photo to July 1867.

Thank you again for your fine work.

I ended up on this site while doing some family history research about an ancestor who had come to the US as a Hessian soldier for the British and in 1781 deserted the British Army at King's Bridge. I was so fascinated by what you had to say I totally forgot my research. Thanks for all the great info and pix!

Wonderful article. Thank you.

Wonderful article. Thank you.

My great grandfather, Feliciano Acierno, owned the Thalia Theatre at one point, following the German and Yiddish generations. Thank you for your extensive history of the building and the community.

I recently found many useful information in your website especially this blog page. Among the lots of comments on your articles. Thanks for sharing.

new york theatre

It shows a great research and knowledge about the surroundings and town. That's a great. Thanks! deals for park and fly

NICE POST SO THSNKS FOR SHARING THIS POST

This article gives me truly quality information. Thanks for providing us such incredible information.

snapchat

Amazing

thanks

Thanks a lot for sharing such an amazing knowledge with us.