This is part I of how business districts repeatedly overran both the “city,” and the residential community that preceded it.

Blue collar manufacturing and wholesale trade, and white-collar office towers, came to Madison Square separately, and left in different directions.

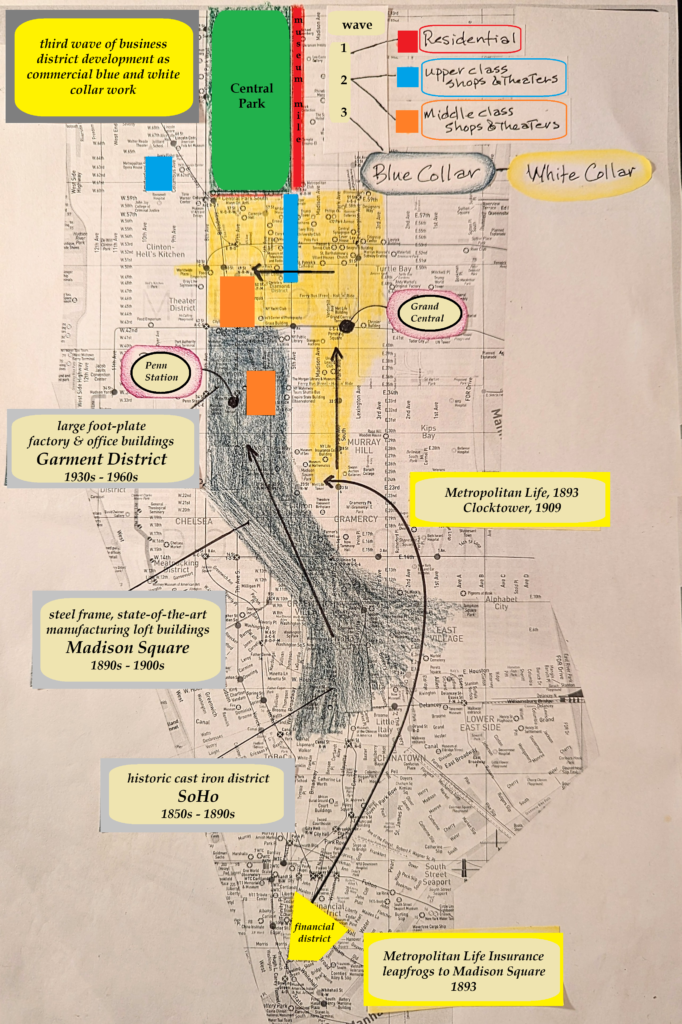

Similar to how shopping and theater districts resolve into upper and middle class location-markets, business districts split into blue and white collar: the Garment and the Midtown Business Districts. The two modes of work co-existed in Madison Square, but developed in different directions, moving toward the latest transit. The Garment District went to Penn Station, and the Midtown Business District went to Grand Central, as blue and white collar versions of “work.”

A pioneering building type came to Madison Square with Metropolitan Life Insurance in 1893. While there were office buildings around Madison Square, Met Life cast a new mold for the white collar office tower that would move up Park Avenue to Grand Central.

Blue collar business districts went down the west side as far as Tribeca, but manufacturing, wholesaling, warehousing, and production came from almost every part of downtown. Blue collar business districts passed diagonally across the island, through Madison Square, stopping at the Garment District just below Times Square. The white collar office tower leapfrogged to Madison Square from the Financial District.

The movement of blue and white collar business districts through Manhattan, toward Penn Station and Grand Central respectively.

Blue collar manufacturing and wholesale trade had been expanding into uptown space since the 1830s and was moving up Fifth Avenue toward Madison Square by the early 20th century in steel frame loft buildings.

The garment district began with a few shops on Delancy Street in the 1850s, and spread as piece work through the tenements of the Lower East Side, and effectively one with the wholesale trade on Broadway.

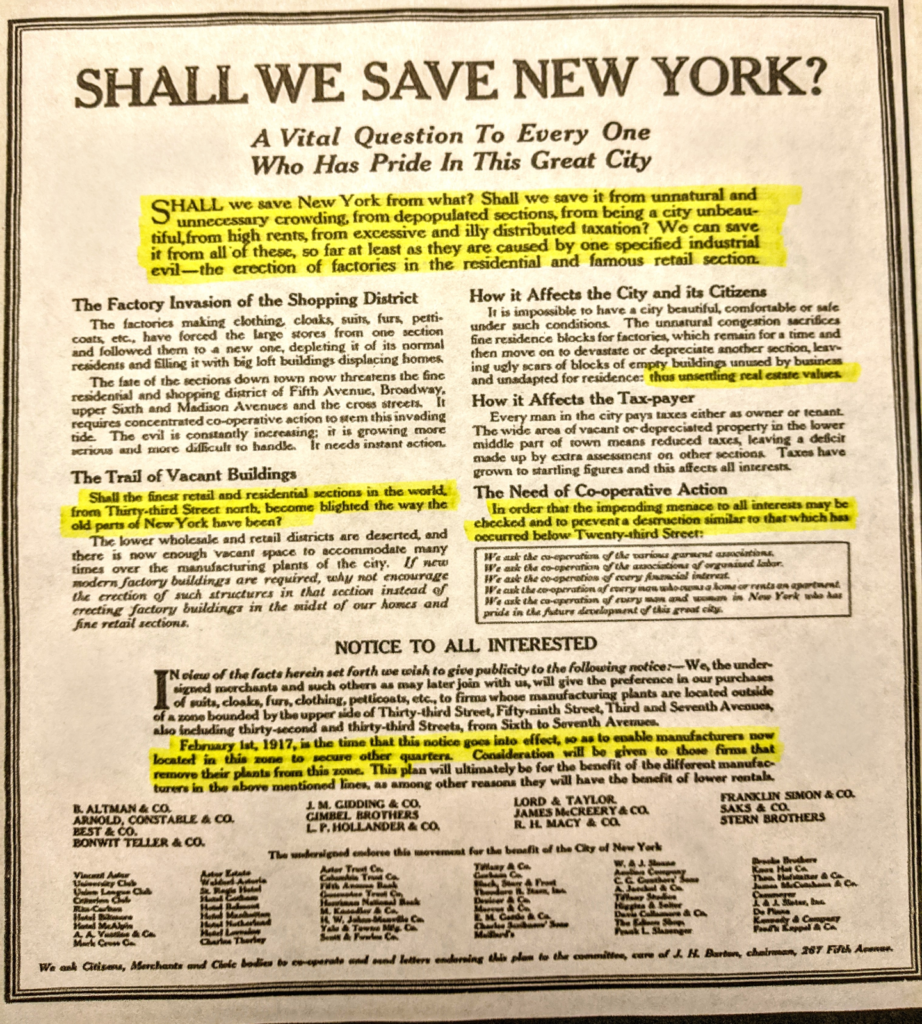

Garment manufacturing transited to Fifth Avenue in “state-of-the-art” manufacturing loft buildings. In 1916, seeing the garment trade approaching Madison Square, the FAA (Fifth Avenue Association) initiated a publicity campaign threatening to boycott the industry if it didn’t remove itself from the Avenue.

The problem was lunch time, when hundreds of cutters descended from the upper floors of factories to sidewalks where the city’s most fashionable shops had been operating for 25 years.

Some fashionable shops had already moved to upper Fifth Avenue by the time of the notice. Given Madison Square and Fifth Avenue’s lack of transit, it’s hard to know if the Garment District would not have ended up where it is anyway. Here’s the February, 1916 notice.

Homes + Commercial Business Districts

Intermixed with densely packed cast iron, steel frame, and skyscraper-filled blocks between City Hall and Central Park are single family homes everywhere.

Buildings belonging to the second wave of development: shops and theaters, formed an armature along Broadway, the Bowery, Fifth Avenue, and parts of Sixth, and along a few select crosstown streets, especially Chambers, Grand, 14th, and 23rd Streets. Most blocks between City Hall and Central Park are comprised of early homes and later commercial buildings, buildings from the first and third waves of development.

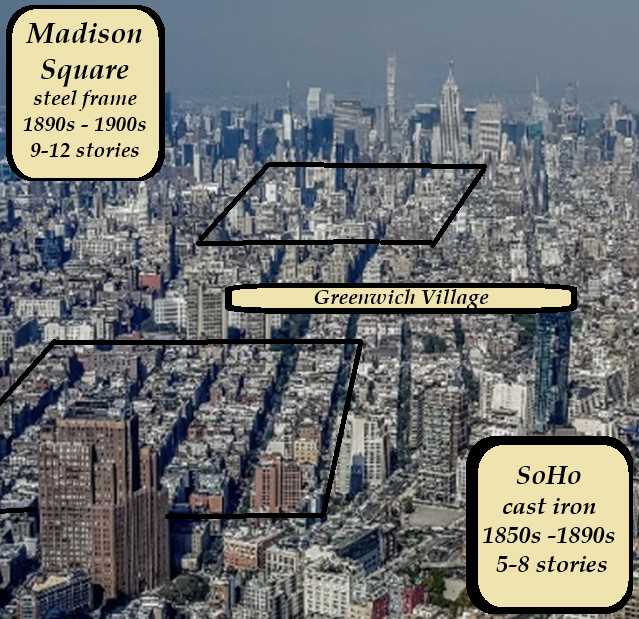

Blocks from SoHo, Madison Square, and Midtown show the evolving uptown-moving pattern in the built environment.

SoHo

In SoHo, early-19th Century Georgian, Federal and Greek Revival homes mix with mid-19th Century cast iron buildings (which sometimes have masonry fronts). The last image is Louis Sullivan’s Bayard-Condict Building (1899), a steel frame building.

There are steel frame buildings in SoHo, especially along Broadway where it made sense to re-develop sites of former cast iron buildings. The building type that makes up the preponderance of the business district in SoHo, however, is cast iron.

Madison Square

Around Madison Square (aka Flatiron, NoMad) mid-19th Century brownstones mix with late-19th Century “state-of-the-art” steel-frame manufacturing loft buildings.

Midtown

In Midtown, late-19th Century brownstones and Beaux Arts mansions mix with mid-20th Century skyscrapers. Note the business district has shifted from blue collar to white collar.

Select bibliography

Burrows, Edwin G. & Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, Oxford University Press, 1999.

Lockwood, Charles, Manhattan Moves Uptown, Houghton Mifflin, 1976.

Okrent, Daniel, Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center, Viking, 2003.

Stern, Mellins, and Fishman, New York 1880: Architecture and Urbanism in the Gilded Age, Montacelli Press, 1999.

Stern, Gilmartin, Mellins, New York 1930: Architecture and Urbanisn between the World Wars, Rozzoli, 1987.

White, Norval, New York: A Physical History, Athenuem, 1987.

Internet Resources

Daytonian in Manhattan, Tom Miller

The New York Historical (formerly The New York Historical Society)

Landmarks Preservation Commission