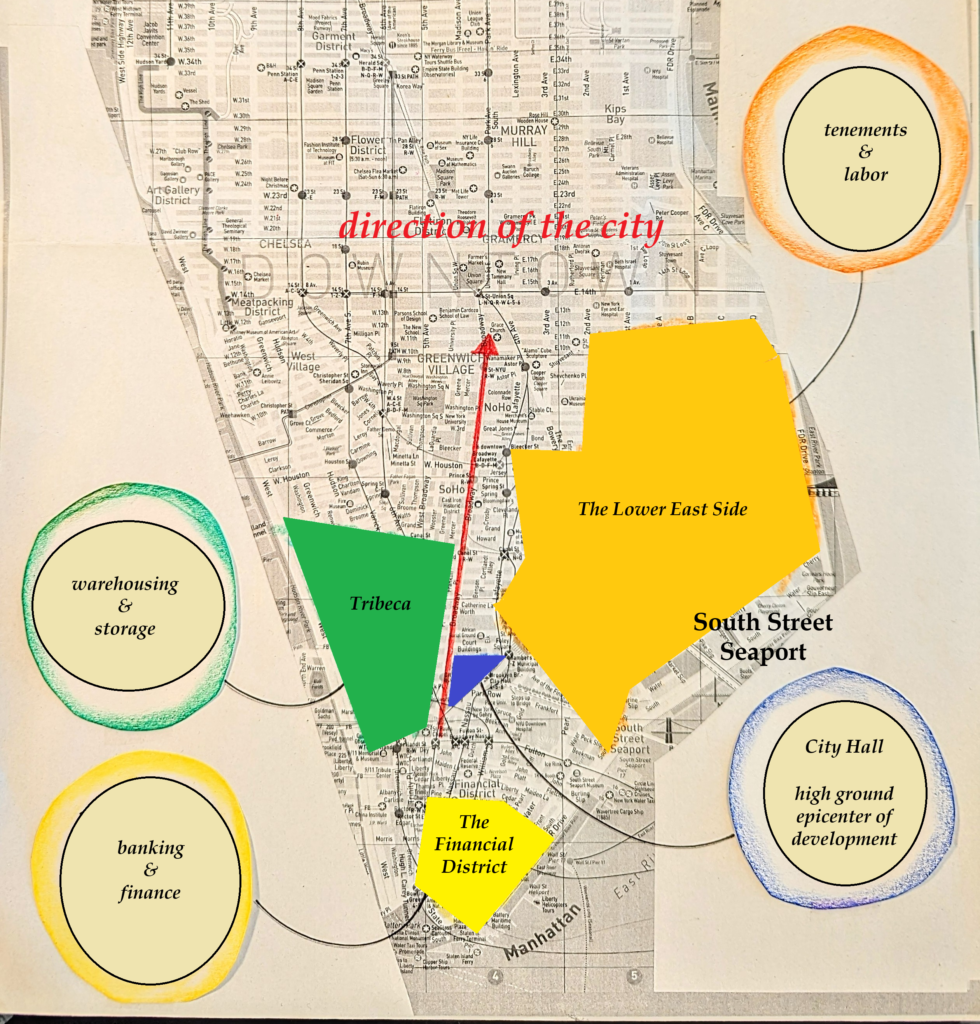

Beginning in the 1850s, the finest shops, theaters and hotels were relocating up Broadway to today’s SoHo. In the other three directions from City Hall, the city began to develop in different ways, differently.

Development in every other direction from City Hall fulfilled the needs of business, and particularly the business of shipping: financing, labor and storage; otherwise banks, tenements and warehouses; today’s Financial District, the Lower East Side, and Tribeca. As the “city” moved uptown, these districts remained downtown, growing and expanding almost block-by-block.

South Street Seaport buildings from the late 18th and early 19th centuries were the hard running engine of the early economy. A working class tenement district formed at one end, and a banking, insurance and finance-related district grew at the other. Pearl Street connected the working class neighborhood of the Five Points (and its most riotous part), with Wall Street through the South Street Seaport.

When Dey and Cortlandt Streets were widened in the early 1850s, on the other side of Broadway and the city, Tribeca’s warehouse history began.

Banks, tenements and warehouses would move uptown in their own ways, and on their own time schedules. What downtown districts didn’t do was uproot, leapfrog, and relocate over and over and over again. Banks, insurance and assurance companies followed the city through the island’s center; tenements developed on the periphery, especially between 8th – 10th on the west side, while warehouse and factory buildings developed between 10th Ave and the shoreline piers on the Hudson River.

Like the uptown city, however, downtown districts of banks, tenements and warehouses overran residential neighborhoods of Georgian, Federal and Greek Revival homes. There were exceptions to be sure, tenements were built in Tribeca, and warehouses were in the Lower East Side, but the preponderance of built environment history was the reverse.

The city is configured in different ways, differently in the four directions from City Hall.

Downtown districts comprise two layers of development: an earlier home, and then either a bank/insurance building, tenement or warehouse, while blocks between City Hall and Central Park, especially along Broadway and Fifth avenue, have three layers of development, one for each modality of life: live, work and play.

A little about each neighborhood.

Tribeca

Trinity Church has owned large parts of Tribeca since the 1690s. There was little good high ground west of Broadway, below Canal Street, where wooden homes were rarely replaced with brick.

St. John’s Park (1803), an early Federal-era residential development built on a manicured park, was far afield on a patch of high ground. Most of Tribeca was a marshy wetland, called Lispenard’s Meadow. Long-term institutions included Columbia University and New York Hospital, while American Express started operations at Jay and Hudson Streets in the 1850s.

With the widening of Dey and Cortlandt Streets in 1851, Tribeca’s commercial transformation into a district of warehouses commenced. Murray and Warren Streets and went year-by-year west of Broadway: Chambers, Reade, Duane and Worth Streets, until the mid-1860s. A burst of construction after the Civil War came around Vanderbilt’s new freight terminal (1866), on the former site of St. John’s Park.

Large warehouses and factories filled blocks leading to the Hudson River over the decades. The shoreline handled the chaos of shipping lines, and the Washington Market thrived nearby the site of the World Trade Center.

As store and loft buildings and wholesale textile markets expanded into blocks of larger warehouses for breaking bulk and trans-shipments, and more wholesale markets, on the other side of City Hall tenements grew taller.

Lower East Side

Here’s a link to a 2010 post that discusses the earlier geography of the Lower East Side.

Jacob Riis, author of How the Other Half Lives, described how the first brick tenements were godsends for the residents, lifting them from the damp, miasmatic cellars of shanties and decrepit houses.

Tenement construction took off after the 1850s with the massive influx of Irish and German immigration, especially when earlier Georgian and Federal homes, already converted to multiple family for earlier arrivals, began to deteriorate.

The New York tenement house got a legal definition from 1867:

Any house, building, or portion thereof, which is rented, leased, let or hired out to be occupied or is occupied, as the home or residence of more than three families living independently of one another and doing their own cooking upon the premises, or by more than two families upon a floor, so living and cooking and having a common rights in the halls, stairways, yards, water-closets, or privies, or some of them.

The rate of return on a 25’ x 100’ lot (the standard lot size) could be three times that of tenements built on larger plots of assembled lots, which would theoretically provide better light and air. Originally New Yorkers, but then immigrants themselves became the builders and developers. The 25’ wide tenement has four windows across because three windows might only have two apartments on a floor, a “flat.”

Tenements often had a saloon or grocer on the ground floor, and four apartments per floor, often with windowless rooms. Bathrooms were shared amongst residents on a floor, although there was no indoor plumbing for decades of tenement history.

The problem all housing was the volume of people, model tenements from the 1850s were housing twice as many as planned by the 1870s.

New York’s population growth is sometimes described as exponential, but growth from 33,000 (1790) to 2.4 million (1910) over 120 years was geometric, and it was front loaded. It works to consider history in 30-year chunks.

Starting with 1790, the population of 33k quadrupled to 125,000 in 1820, then quadrupled again to 515,000 by 1850 (when the refrain was Above Bleecker!). The population doubled over the next 30 years, to 1.3 million by 1880. Then, at this now enormous number, the population stunningly doubled again, to 2.3 million by 1910. (Still, had it been exponential, a great many more people would have come at the end.)

For nearly a century people poured in and out of the Lower East Side in an ongoing unfolding human history that warranted Ellis Island, and Emma Lazarus’s version of the Statue of Liberty, and a museum (the Tenement Museum) that receives 250,000 visitors a year. It’s existentially fascinating there exists such a museum at all.

Tenements were built in uptown districts since the horsecar lines of the 1850s, but the Lower East Side saw a century of chronic tenement construction, a tenement district of tenement districts, often of intolerable densities.

Legislation in 1879 and 1901 amounted to a race between laws requiring greater airshafts for ventilation and sunlight, and the drive of developers to be able to lease out as much square footage as possible. The result is a rudimentary order of tenement-types: Pre-law, Old Law, and New Law. In the end, the developers won as the solution would be to tear the buildings down.

To different extents, different groups recreated, reinvented, and/or assimilated old cultures into new American lives through the medium of the tenement. And working class and slum conditions did not mean middle class lives weren’t being lived in the tenements, some families had pianos, if little space for one.

As the “city” moved uptown, poverty didn’t move, and the Lower East Side remained an expanding portal of general struggle and survival, generationally growing as different peoples sorted in and out in a uniquely human chaos.

Two histories, opposite sides of the same “social coin,” speak directly to the privations of tenement housing: the history of American gangs, and the origins of self-help groups.

The Ancient Order of the Hibernians (1836), B’nai Brith (1843), The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (1883), and Sons of Italy (1905) are global, multi-million dollar ethnic self-help groups, and all were founded within a short walk of each other in the Lower East Side (B’nai Brith was founded a year earlier in San Francisco).

Then, from the headquarters of the Forty Thieves in the 1820s (now roughly 500 Pearl Street and the reputed site of the first American gang), to the Ravenite Social Club on Mulberry Street of late-20th century mafia history, is a 1/2 mile walk and covers 200 years of “gangland” history. Other associations calling the area home through time were: various Five Points gangs (the Dead Rabbits, Chichesters, Plug Uglies…), the Bowery Boys, Whyos, Paul Kelly’s Five Points Gang, the Eastmans, the Black Hand, and a good part of 20th century Mafia history.

Interesting too, gangsters came from the Lower East Side, families didn’t; Lucky Luciano, from the Lower East Side, would organize the families, who were from other parts of the city.

The black community was a significant part of the neighborhood around Paradise Square and the early Five Points from Colonial days. The black population was disproportionately large during the slave trade and dwindled within the city’s growing numbers, until the Draft Riots of 1863 when many were driven from the city. The story of the rise of the black community though Manhattan neighborhood by neighborhood and church congregation, especially St. Philips, followed by the Great Migration and the Harlem Renaissance, is integral, singular and inspirational in New York City history.

In the 1840s people were dying from the conditions in cellars of the Five Points, and decades later were falling from rooftops and fire escapes on hot summer nights trying to breathe at night in overcrowded tenements. Nothing tracked more directly with the tenements of the Lower East Side than the Orphan Trains, which ran from 1854-1929, for 75 years, about the time they started tearing down tenements in the Lower East Side.

The Sunshine and Shadow story of New York traditionally contrasts the Lower East Side with Madison Square, or the Fifth Avenue mansion life of the Gilded Age. It’s interesting that the Lower East Side (with its beginnings in the Five Points), and the Financial District have the two longest-lived contiguous histories of any neighborhood, other than perhaps Greenwich Village.

The Five Points and Wall Street were connected by Pearl Street, the wholesale market whose cheap-side was above Peck Slip and otherwise ran through the South Street Seaport.

The Financial District

Just some basics about what’s likely New York’s most famous neighborhood.

The Financial District could broadly describe everything below City Hall, though between City Hall and Wall Street is the Insurance District. The first half of city history happened within these tight, crammed blocks. It is a catch-bin of architecture with buildings of every style and technology, from Georgian homes, cast iron buildings, to Art Deco and Modern skyscrapers.

Shipping lines and freight forwarders were among early businesses, and later corporate headquarters located amongst buildings for the business of business. The first “office building” was the Trinity Coal (1855) on Broadway across from Wall Street.

The Bank of New York was started by Alexander Hamilton in 1784, and Aaron Burr started the Manhattan Bank in 1799, after which both banks were on Wall Street. The Tontine Coffee House, at the corner of Wall and Water Street, held auctions for commodities in the hulls of nearby ships. Inside dealing led to a splinter group to break off and start the New York Stock Exchange, further down the block. The Bank of New York was one of their first customers.